Spotlight on the DHR Conservation Lab: Welcome to the Betsy Project!

During the autumn of 2018 the conservation lab at DHR started an exciting new project thanks to a Maritime Heritage grant from the National Park Service. Conservator Chelsea Blake has joined the DHR team and will be dedicated during the next two years to preserving artifacts recovered from underwater excavations conducted in the early 1980s on the Betsy, a ship constructed in 1772 in Whitehaven, England.

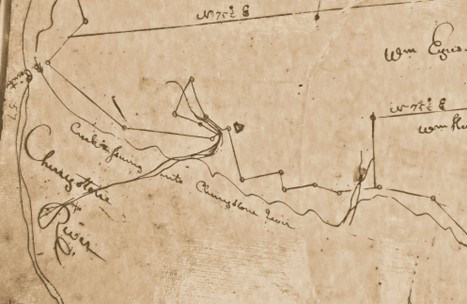

Originally, the Betsy served as a collier, a ship used to transport coal from Britain. But during the Revolutionary War, the Betsy was one of many ships scuttled by the British Navy in the York River in an attempt to prevent the French navy, a key ally of the Patriot cause, from drawing close to Yorktown. Fortunately for the Patriots, the British had miscalculated the range of the French guns and the French ships were still able to fire on the coast during the Siege of Yorktown, the final battle of the American Revolution.

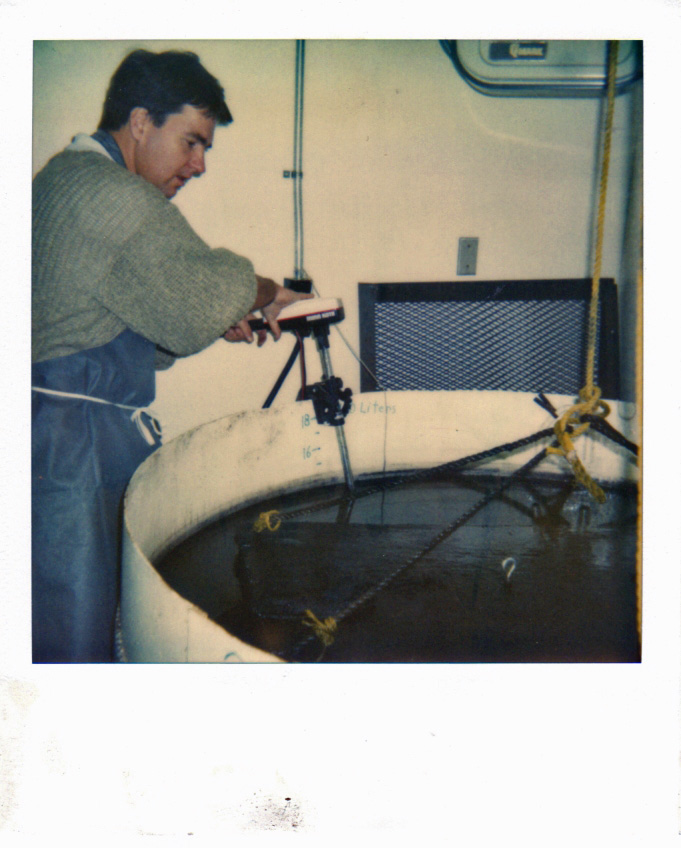

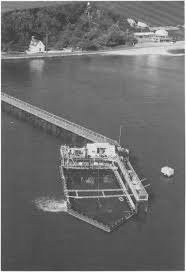

In 1982 archaeologists, led by then-DHR archaeologist Dr. John Broadwater, erected a cofferdam around the area where the Betsy had sunk. The cofferdam, a structure built into the riverbed around the site, allowed the murky water of the York River to be filtered, thereby providing better visibility for the underwater archaeologists who excavated the ship’s remains during the Yorktown Shipwreck Project. About 50 percent of the ship’s contents survived, and these artifacts once retrieved, were then conserved, catalogued, and deposited in DHR Collections.

So what’s up with this new Betsy project?

The short answer is that conservation is not a static process. Fast forward to today, and it quickly becomes clear that these artifacts, once treated, continue to need monitoring and retreatment. Such is the life of a conservator and a conservation lab.

For instance, in the late 1980s and early 1990s treatment of waterlogged organics with any real success was a fairly new undertaking for conservators.

When organic materials such as wood and leather decay, their cellular structure is weakened as biological activity eats away internally at that structure. Importantly, if allowed to dry without treatment, the stresses caused by capillary action (the force applied to the cells as water departs) will cause the artifact to shrink like a dried sponge, crack and become unrecognizable and fragile.

Bulking agents are often used to support the cellular structure of the artifact during the drying process, and this helps to reduce shrinkage.

Throughout the original treatment project, the Betsy’s contents were treated with multiple bulking agents including polyethylene glycol, sucrose, or acetone/rosin. Conservators now have a better understanding of how to treat waterlogged wood, using methods distinct from the ‘80s and ‘90s, when conservators applied a lot more bulking agents to avoid shrinkage.

For the Betsy artifacts, the heavy application of bulking agents has led to concerns about these agents migrating to the surface of an artifact. Such action often obscures the surface of the object and makes it feel sticky or appear waxy. Fluctuations in humidity during the past 30-plus years have caused such migrations to happen with most of the organic artifacts from the Betsy.

The DHR Conservation lab will spend two years on this re-treatment project thanks to the National Park Service Maritime Heritage Grant.

Our first step in the retreatment process is to modernize DHR’s records for the Betsy collection by creating a digital inventory of artifacts and digitizing the original treatment records. After this, each of the more than 1,200 artifacts will be individually assessed for their condition and conserved.

Additionally, improved storage of the collection will be addressed. Since the collection’s original treatment, storage materials for numerous artifacts have degraded over time, which can result in damage to an artifact when handling it today. Hence, storage materials will be replaced with newer archival materials to ensure the safety of the artifacts for years to come.

Stay tuned for more information and object spotlights from the Betsy Project!

Chelsea Blake, Conservator, Department of Historic Resources