Modern Indians A.D. 1800–Present

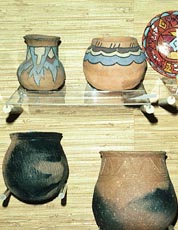

Traditional and 20th-century Indian pottery at the Pamunkey Indian Museum.

In the 1800s, the prevailing white culture in Virginia wanted to push the Indians off their homelands. Pressure was brought to remove each of the four remaining reservations and end the people's legal status as tribes. This policy meant dividing, with the Indians' consent, all of a reservation among each of its members and removing all state services to the tribe.

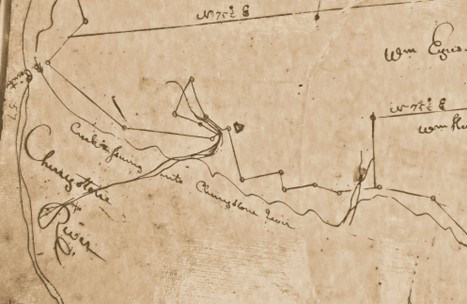

The Gingaskin Reservation on the Eastern Shore was legally subdivided in 1813. Unable to withstand legal pressure and being very poor, the people sold their land for profit. By 1850, all of the original Gingaskin Reservation was in white hands. The last parcel of the Nottoway Reservation was divided in 1878, although many families held onto their land into the 20th century. The Pamunkey and Mattaponi, the last two reservations, withstood attempts at termination. Though the people were poor, they maintained their tribal structure and treaties with the Commonwealth. Today, their reservations are two of the oldest in the nation, symbols of a people who refused to give up.

Their example has been an incentive for the non-reservation Indian people, who, around the time of the Civil War, began to resurface as identified enclaves. In the early 1900s, these enclaves reorganized into tribes. The move by Indian descendants to form tribes was seen as a threat by some people who wanted to keep the white race "pure." Led by Dr. Walter A. Plecker, a group called the Anglo-Saxon Club of America prevailed upon the General Assembly to pass the Racial Integrity Law in 1924. According to this law, in matters of births, marriages, and deaths, the Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics recognized only two races—white and black. U.S. Census figures in 1930 showed 779 Native Americans living in Virginia; by 1940, the figure dropped to 198. In effect, people of Indian descent did not exist. Since the Indians were not accepted into white churches and schools, they opened their own. However, Indian schools in Virginia did not go beyond seventh grade until the late 1950s.

The Civil Rights movement promoted opportunities for education and employment for the Indians as well as other minorities. The requirement for school integration during the 1960s removed the need for separate Indian schools, or for Indian students to leave the state to obtain high school or college education. After the movement was actively in force, doors opened for the more rapid advancement of Indian people into all professional levels of society.

Many activities among Virginia's Indians continue to build a strong sense of identity among the tribes. Tribal centers have emerged as symbols of unity, similar to the role played earlier by Indian schools and churches. Tribal dance groups are commonly seen at the increasingly popular tribal Pow Wows, which enable Virginia Indian tribes to meet with the public and demonstrate crafts, dances, and share oral histories.

Indians selling their pottery at a Pow Wow.

At the same time that Virginia Indians' self-images are changing, the popular view of them is shifting, too. More people recognize that the world has inherited from the Indians a legacy of many valuable foods and words. Corn, one of the world's most precious foods, is one of their gifts. They also cultivated squash, beans, and tobacco. The names of many Virginia counties, cities, towns, and roads are Indian names. Common words, including moccasin, raccoon, hickory, moose, chipmunk, and skunk are Virginia Indian words.

Today there are eleven organized tribes in Virginia. Two tribes, the Pamunkey and the Mattaponi, have small reservations in King William County. Their state reservations date from the 1600s. Nine other incorporated groups are officially recognized as Indian tribes by the Commonwealth of Virginia. They are the: Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Indian Tribe in Southampton County; Chickahominy Indian Tribe in Charles City County; Chickahominy Indian Tribe–Eastern Division in New Kent County; Monacan Indian Nation in Amherst County; Nansemond Indian Tribe in the City of Chesapeake; Nottoway Indian Tribe of Virginia in Southampton County; Patawomeck in Stafford and King George counties; Rappahannock Indian Tribe in Essex, Caroline, and King & Queen counties; and the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe in King William County.

During the 1990s, six Virginia tribes pursued federal recognition through the Bureau of Indian Affairs: the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, Chickahominy Indian Tribe–Eastern Division, Monacan Indian Nation, Nansemond Indian Tribe, and Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe. After the Bureau indicated that it could take decades to receive administrative recognition, the tribes in 1999 formed VITAL, the Virginia Indian Tribal Alliance for Life. VITAL decided to pursue Congressional recognition.

Since 2000, bills have been introduced to both houses of the United States Congress seeking federal acknowledgement for Virginia tribes. VITAL recognizes the right of Indian tribes to self-government and supports tribal sovereignty and self-determination. VITAL is also a research and education organization dedicated to a wider understanding and appreciation of the ideas and knowledge of indigenous peoples, and to the social, economic and political realities of the American Indians of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe continued to seek recognition though the Bureau of Indian Affairs. After a tumultuous vetting process and multiple appeals, the Pamunkey achieved federal recognition on January 28, 2016, becoming the first Virginia Indian Tribe to do so.