Late Woodland A.D. 900–1600

People throughout eastern North America lived in thousands of large villages. Hundreds, if not thousands, of people resided in each village, organized around a complex economic, social, and political structure. The people increased their reliance on intensive gardening for most of their food.

Although the developments were not as elaborate in Virginia, Late Woodland people developed strong identities as each adapted to its local setting.

In southwestern Virginia, the transplanted Mississippian and local cultures thrived; in the Shenandoah Valley, the Earthen Mound Burial culture grew; and to the east, the Coastal Plain Indians prospered.

Village life broadened the social sphere, wealth, and security of the residents. The resulting social structure demanded more coordination of functions from the tribal leader, who assumed greater responsibility and status.

The Late Woodland people achieved a richness of culture that was unmatched to date. Sophisticated craftsmanship created a wide range of pottery forms, stone artifacts, and bone tools such as awls, fishhooks, needles, beamers, and turtle shell cups. Accoutrements for the rich, such as beads and pendants, were made from imported shell and copper. Ceremonial and symbolic objects of stone, copper, and shell were also manufactured. A wide range of rather elaborate burial customs reflected the people's fascination with the passage from life to death.

Villages became more complex; house building more substantial. In typical villages, various sizes of house were placed in rows around a plaza with perhaps a council house or temple elevated on a nearby mound. A palisade may have surrounded the entire village.

In farming, beans arrived from the southwestern lands about A.D.1000 to join corn and squash as the three major crops. Tobacco came by way of Mexico. Animals, especially deer and turkey, were heavily hunted, as well as turtles and sometimes bear and elk. A wide array of natural plants, nuts, and berries were gathered.

Since the preservation of artifacts from the Late Woodland period is outstanding and the cultures are rich and dynamic, archaeologists have been able to collect much information about group variation across Virginia. Although many of the pieces are missing, we know certain things about a few of the more prominent groups.

Southwest Virginia

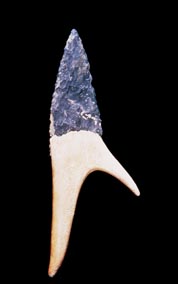

Knife point hafted onto deer antler created an efficient tool for cutting.

Local cultures developed in the mountains and valleys of western Virginia. Southwestern Virginia is said to be a crossroads of Native American culture. Mississippian people entered the region along the Tennessee River system. Ohio Valley groups came in by way of the New River, and Piedmont cultures advanced up the Roanoke River.

The people of southwestern Virginia formed tribal cultures very similar to the groups in the southern Piedmont of Virginia. They made a wide array of pottery tempered with sand, limestone, or shell, and impressed with cord and net. Their homes, about 15 to 20 feet in diameter, were constructed of multiple poles anchored deep into the ground. The tops of the poles were bent over and tied to form a dome-shaped house. The houses were covered with either thatch or bark and clustered around a plaza in the center of a walled village. Daily life was based on intensive gardening, supplemented with gathering wild plants and hunting animals.

Mississippian

Mississippian culture contrasted greatly with the local cultures in southwestern Virginia. (The term "Mississippian" is used because some of the first sites of the culture were found along the Mississippi River.) A regional phenomenon, the Mississippian culture became widespread throughout the Midwest and southern United States. In Virginia, this culture made its way into the extreme southwestern corner of the state.

The villages of the Mississippian culture were much larger, more complex, and more permanent than that of most Late Woodland cultures. The more settled and abundant life of the Mississippian culture led to fully developed chiefdoms ruled by chiefs and subchiefs. In a chiefdom, a few highly ranked people at major centers directed the economic, socio-political, and religious activities of thousands of people living in a large region. The position of chief became a permanent office and social inequality became a basic rule.

The people loved games of competition, such as chunkey. In this game contestants threw spears after rolling stones and chased them in contests against the best players of other villages.

Here in Virginia, the best preserved Mississippian site is Ely Mound in Lee County. A townhouse sat on the tall, distinct, flattop mound that overlooked the village and the plaza where the game of chunkey was played. The townhouse was like a combination church and town hall, and was the major focal point of village activities.

Earthen Mound Burial Culture

In an area that includes both the Shenandoah Valley and the northern Piedmont, there existed a culture from A.D. 950 to the time of European contact whose defining characteristic was that it buried its dead in earthen mounds. Visible monuments on the native landscape, some mounds reached a height of at least 20 feet. These mounds were distinct from the Mississippian mounds in that they served as the final burial place for hundreds, and, in some cases, thousands of people.

The mounds were sacred places where ancestors were honored. Sometime between 1760 and 1781, Thomas Jefferson examined one of these mounds near Charlottesville in what many consider to be the earliest scientific archaeological excavation in America. He later wrote that he watched Indians in the mid-18th century walk directly to the mound and stand before it for some time with sorrowful expressions, before they left the mound and pursued their journey.

Coastal Plain Culture

The Coastal Plain offered a unique environment of saltwater and freshwater rivers, bays, and marshes. People adapted to it by relying on fishing, particularly for the shad and sturgeon that spawn upriver. From the shallow salty waters, they gathered oysters. Tests on great heaps of discarded shells, called shell middens, show they gathered oysters in the late spring. Oysters provided food while the people waited for the wild and cultivated plants to grow, and were dried, stored, and used later in the year.

By A.D.1300, the Coastal Plain tribes had grown to form sedentary villages supported by small, short-term hunting and gathering camps. Relying more and more on horticulture, the people favored the floodplain and low-lying necklands of rich sandy soil for village sites. Coastal Plain people built their villages creating many long, oval houses either spaced close together and surrounded by a palisade, or dispersed, separated by fields for gardening.

Through most of the Late Woodland period, the numerous villages of the coastal groups formed independent tribal societies, but by the 16th century, chiefdoms developed. Crowded, competing for territory, and needing to expand their economic systems, the weaker tribes were forced to pay allegiance and tribute to the stronger ones. In return for goods paid in tribute, the member tribes were protected in times of attack and need.

Burial practices differed according to the status of the person in the tribe. Single burials have been found, as well as ossuaries. Ossuaries are large pits where Coastal Plain people periodically performed ritual burial ceremonies and interred the bones of their ancestors after their bodies had decomposed.