History on the James, Batteaux From the 18th to the 21st Centuries

History on the James, Batteaux From the 18th to the 21st Centuries

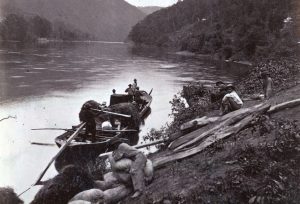

A peeled sapling, roughly eighteen feet long, plunges into the water and strikes bottom with a gravelly ‘thunk’. You are now connected with the riverbed and lean forward, putting a shoulder to the pole to bear your weight. At the same time, you start walking forward – pushing. Below you, wooden planks polished by sandy feet glide by like some prehistoric treadmill. Look down and count the ribs, eight will pass under you before the short walk is over. The boat moves forward, a small wake vees out from the bow and heads towards the bank line marking your progress. Turn, lift the pole, and walk back to do it again. Plant the pole and stamp, plant and stamp, plant and stamp. This is the rhythm of the boatman and an ancient human connection to our rivers.

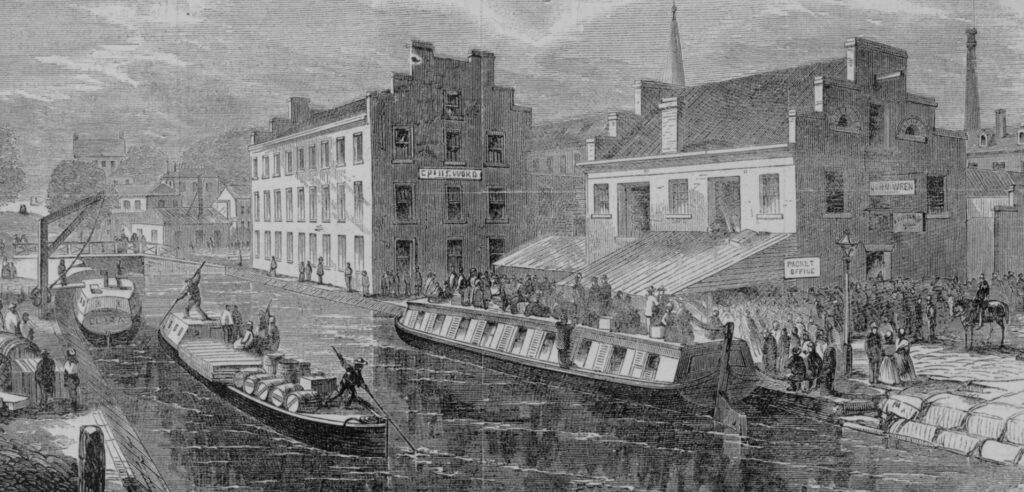

For the past 37 years the James River Batteau Festival (JRBF) has honored the history of the river by replicating wooden cargo boats knowns as batteau (the plural is batteaux) and piloting them from Lynchburg down to Maiden’s Landing in Powhatan County at the Rt. 522 bridge. The replica batteaux are built from oak and pine, range from 40-50 feet long and are a little over six feet wide. Shelter from rain may be a canvas tarpaulin stretched over hoops, under a bankside tree, or maybe just beneath the wide brim of your hat. Accommodations aboard are spartan but devotion to the festival is fierce.

It takes dedication and many months of planning to pull off the weeklong festival. Even through Covid, the group persisted their annual homage to the boatmen of the past and this year was no different. The 120-mile pilgrimage involves 10-15 batteau and many, many people in kayaks and canoes who come along to witness the waterborne parade. It’s a beautiful spectacle to witness, the slender honest wooden craft poled along just faster than the current and steered by two massive oars, one forward and one aft, known as “sweeps”. But it’s not just beautiful, it’s our history – complex and worth contemplation. Let’s take a moment to dive in and understand the importance of batteaux and their inland sailors

.

From Boat to Batteau

Long before the railroad chuffed from the ocean to the mountains, and long before interstates penetrated every region of our state, rivers and creeks were our interstate transportation system. Most people would be floored to realize just how many little creeks carried large batteau loaded with tons of supplies inbound and crops outbound. Even the Shenandoah and the New River valleys were inland navigation systems. Wherever a continuous stream of water a couple feet deep could be maintained, cargo boats went.

The earliest batteaux appeared in records in 1775 and were likely an innovation borne out of environmental adaptation. A major flood in 1771 destroyed vessels of the James River basin, mostly dugout canoes and small boxy flatboats inept at handling the frequent rapids and rocky shelves of the river. Anthony Rucker is attributed with the design of the earliest batteau form. His experience in the French and Indian War likely introduced him to slender, pointed vessels built and operated by French trading enterprises. Certainly, the name ‘batteau’ which came into popular use during the late 18th century in Virginia speaks to the French connection.

Batteaux were long, narrow boats with two pointed ends. Some had simple triangular ends, and some were built with sweeping, graceful curved ends. Cargo was carried in an open hull and commonly set on a number of fore-and-aft planks set on top of the frames, or ribs. The genius of batteaux is that they combine the handy nature of a slender log boat with a more capacious size and flexibility. Most loaded batteaux had a draft of less than two feet, meaning they could navigate the river in near-drought conditions. Built up to seventy feet long, batteaux were steered at both ends via long oars called ‘sweeps’. Propulsion came from poles, often iron tipped to help get a grip on slippery rock bottoms. Despite some accounts of batteaux being disassembled at the ends of their transport and sold as lumber, most batteaux lived long working lives.

Ownership of batteaux ranged from plantation holders, who sought to ensure carriage for their crops, to transport companies capitalizing on regional freight demands, to individuals who built or bought their own to haul on contract. Batteau sailors, better known as ‘boatmen’, were both black and white, free and enslaved. For many boatmen, the river was their lives and homes. A tarpaulin protected them, minimally, from rainstorms. There was no protection from the sun besides a wide brimmed hat. Labor was continuous and, at times, dangerous. The daily toil of poling a boat upstream may be upset by a suddenly-rising river due to upstream storms. Bateaumen, as they were also known, started off with the pole and learned to handle a sweep, and then finally ascended to the rank of ‘headman’ whose job it was to read the river and direct the boat through rapids and whitewater. They acted as pilots and lifeguards on the river. Frank Padget, a batteau headman, saved nearly forty passengers on the Clinton, a canal boat caught in a dangerous flood after having broken its tow rope near Balcony Falls. Padget drowned trying to save the last passenger. On more than one occasion, boatmen were swept overboard and into a watery grave. Operating a batteau was a year-round job and only ice or low water would stop the boats.

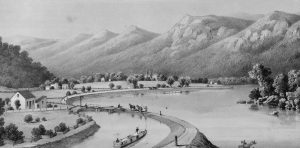

By the early 1800s, movement of commodities throughout central Virginia was borne almost entirely in batteaux. Batteaux and inland navigations were critical infrastructure in an early supply chain. It didn’t take long for the young republic to realize that batteaux traversing natural river channels left too much as risk to floods, shoals, stranding during periods of low water, and an ever-increasing number of mill dams blocking creeks and river. A heavy spring rain could leave roads too muddy and rivers too swollen for goods to move. Navigation companies were authorized by the state government to improve waterways for navigation and dig canals for alternate safe passage. Today, we might think of these companies as regional VDOT offices focused on rivers and creeks. They had the right of imminent domain and the backing of the sheriff to enforce open waterways. Navigation companies had legal authority to mandate locks and bypass canals around mills that dammed up navigable waterways. They also had the authority to levy tolls at certain inspection points to pay for the maintenance of channels. The constant job of maintaining a waterway meant chopping away fallen trees, digging away shoals, and clearing rocks tumbled into the channel. In other places, rocks were placed to create sluices, or linear channels of directed water allowing boats to pass over otherwise treacherous shoals or ledges.

In 1785 the James River Company was formed and by 1789 a short series of canals and locks allowed passage of batteaux around the falls in Richmond. This was the first operating canal and lock system in the United States. Eleven years later, portions of the river channel were sufficiently improved to allow shallow draught batteaux passage nearly 200 miles up the James from Richmond. These improvements, however, were a stopgap to the more serious need for reliable inland navigation. A continuous canal, “slack water navigation”, was the goal. Slack water meant dammed portions of the river where little to no current would thwart upstream movement connected by long sections of canals with no currents.

For the next four decades, the most reliable channel from Richmond to Lynchburg, and beyond, remained the river itself. While construction of locks, guard dams, and aqueducts was ongoing, there were frequent stoppages such as when floods washed out the canal banks or when wood-lined canals were too leaky to support traffic. Meanwhile, batteaux carried goods and people up and down the river. Inside the canal, larger canal boats were towed by mules and could carry much heavier cargoes but were limited to only those times when the canal was operational and on sections that were open. Batteaux were provided access to the canal during the 1830s and ‘40s, sometime without charge, to keep traffic flowing and attract the attention of transport companies and boatmen. In 1840, the canal was complete from Richmond to Lynchburg, a 146-mile continuous maritime trunk.

Batteaux to Canal Boats

Fitful attempts to dig a continuous canal up the river led to a state takeover of the James River Company in 1820. Its new name became the “James River & Kanawha Company”, indicating a serious intention to complete a canal all the way to the Mississippi Basin. Getting a boat over the 3,000’ Allegheny mountains had thwarted previous engineers. Several engineers had suggested an intermediate turnpike over the mountains to connect river valleys. A turnpike was created and operated by the company, which became the modern-day U.S. Route 60. However, the desire for a continuous canal through the mountains was not abandoned.

During the 1820s and 1830s canal construction was at a feverish pace in the United States. British examples of canal success spurred development along the mid-Atlantic and northeastern seaboard to drive canals westward and into new markets. At the same time, the railroad emerged into a dubious world. On July 4, 1828, a groundbreaking ceremony was held for the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal near Washington DC. The very same day, and nearby, a groundbreaking ceremony was held for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (Hobbs 2009). The president attended the canal ceremony.

Pressure to develop canals and connect distant regions reduced the mountain problem to a simple engineering challenge. The James River & Kanawha Company redoubled its efforts in the 1830s by hiring new engineers and attracting additional funding from the General Assembly to initiate a phased construction of canals as far up the James as Covington. The phases were known as ‘divisions’. The First Grand Division was from Richmond to Lynchburg, Second Division was from Lynchburg to Pattonsburg (near present-day Buchanon, Virginia), and the Third Division was from Pattonsburg to Covington. Each division took on increasing challenges due to the steep rise in the river.

Batteaux and canal boats of the James River and its tributaries tapped into the largest watershed in the state. The James River rises in the Allegheny Mountains in Botetourt County, traverses the Shenandoah Valley picking up the Maury River, cuts through the Blue Ridge Mountains from Glasgow to Big Island, and slows down through the rolling piedmont region where it is fattened by several navigable tributaries such as the Rivanna, Willis, and Slate rivers. During the early 1800s wheat and iron production expanded in the Shenandoah Valley. A bushel of valley wheat would be harvested, transported by wagon to a landing on a navigable creek or river, transported down the James to Richmond, ground into flour at the Gallego or Haxall mill, loaded into an ocean-going vessel, and often ended up in South America where the return cargo was often coffee. Iron rich ore was dug from the Virginia mountains, blended with crushed limestone, and poured into giant charcoal-fired furnaces. Periodically, the furnaces were tapped, and molten iron ran like a bright yellow river into molds to form pig iron. A heavy cargo of ‘pigs’ would end up in Richmond and be re-melted at Tredegar Iron Works to become cannon for the army, perhaps an ornate cemetery fence, or even part of a locomotive that would end up being the death of the canal.

By the late 1850s, railroads offered increasing competition and the uppermost portions of the canal, the Third Division, were abandoned for lack of funds and a struggle over management. Boats continued to use the canal and batteau continued on Virginia’s waterways well into the 1880s, but the golden age of inland maritime commerce was over.

Honoring Batteaux

Since 1985, replica batteaux have floated from Lynchburg to Maiden’s every June. The 120-mile stretch takes eight days to complete with stops along the way to camp and swap stories. In several places, such as Cartersville and Scottsville, the bank line is lined with people who have come to see the spectacle of 10-15 batteaux make a landing for the evening and to send them off in the morning. Along the river, canoes and kayaks form a flotilla of supporters who come along to enjoy the scene. The James River Batteaux Festival celebrated its 37th year in 2022 and has recently completed a successful run. The individuals who build and crew the boats do it out of a passion for the river’s history. With nearly four decades of success, the festival has become a generational event for some families. Some of the boats also provide educational experiences for school groups and civic associations outside of the festival.

Batteaux used in the festival are replicas of original boats documented in archaeological examples or found in historic documents. Built from oak and pine, they float, pole, leak, and rot just like their historic forebears. Entirely volunteer built, the batteaux are mostly between 40-50 feet long and weigh well over a ton or two when the wood becomes partially waterlogged. They carry hearths similar to one found in an archaeological example from the Great Turning Basin. In the morning most of the boats have a wisp of smoke from their stern ends as breakfast is cooked and coffee boiled. These boats are built in back yards, at night and on weekends, and come from trees specially selected for the task. The planks, some of which are nearly forty feet, are custom sawmilled. While the festival takes a downstream-only approach, to ‘go with the flow’, a few of the crew have done some serious upriver poling. The crew I was with was one such boat.

In 2012, Andrew Shaw was funded by National Geographic to retrace the River Commission of 1812. John Marshall, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, was tasked by the Virginia legislature to survey the upland water route for the canal. He set out with a boat and a twenty-two-man survey party to prove that a continuous maritime thread into the Ohio drainage was not only desirable, but achievable from the upper James. Marshall’s report not only supported the theory but proved its viability and was a testament to the humility of the Chief Justice who was willing to put his hide on the line. Shaw reconstructed a batteau for the task and set out from Richmond to pole up the river, portage their boat overland through the mountains as if tracing the way for a canal, and then set out into the wild New and Greenbrier rivers. It was the first time in 125 years that a wooden boat of this magnitude had tackled class III and IV rapids. They crashed down through standing waves more than head tall, the oak hull bent with the punishment, but boat and men withstood the crucible.

This year I had a chance to join the Mary Ingles, a boat jointly owned by Andrew Shaw and two fellow batteaumen. A relatively new batteau, the Mary Ingles is forty-three and a half feet in length and ninety-three inches in maximum breadth. As a maritime archaeologist, I am a firm believer that you should never pass up an opportunity to sail aboard an historic replica of a vessel you study. It is simply the best way to see them work and understand the systems that make them work. All the book learning and archaeological study in the world can’t compete with an experience on the real thing. It also provided an opportunity to speak with the builder of the Mary Ingles, and other batteaux, who have also studied the archaeological remains excavated from the Great Turning Basin in the 1980s.

Kevin Ferrell, a commercial Halibut fisherman whose eye was constantly reading the river to pick the best path was our headman. Sebastian Backstrom, a professional arborist, was on stern sweep and kept his eye on the river ahead at all times. With Capt. Shaw, three could not have been more hospitable. It was clear from their years of experience together how a batteau crew would have been able to communicate clearly without saying a word to guide a boat through tricky rapids. It was only to us landlubbers that commands were needed to pick up a pole and put our backs into it. Other guests were aboard that day to learn about the river and its history. Andrew made sure we did just that. We poled up side streams and tried to climb the Hardware River to visit an aqueduct. Though we tried to remove it, a downed tree prevented that diversion. Conversation nearly all day focused on regional history and river history. For dinner, we poled the boat up a creek and ate dinner beneath a beautiful stone culvert that once carried a canal over a creek. During dinner a coal train thundered over our heads, the old masonry held fast as a testament to its design and craftsmanship.

In the long shadows of the evening, we put ashore at the mouth of the Slate River and I disembarked tired but thrilled. Getting to know and care for the history of our waterways means doing serious research in the archives but it also means being on, and in the water. For many JRBF participants floating the river each June is paying homage to the boatbuilders, headmen, engineers, masons, navvies, lock tenders, and boatmen who sculpted the James River and its canal. Dedicated volunteers of the James River Batteau Festival and their sister organization, the Virginia Canals & Navigation Society, represent a core of our inland maritime past, and one that is millennia deep.

For more on the James River and its history, check out the Virginia Canals & Navigation webpage at www.vacanals.org.

Text and photos by Brendan Burke, DHR