Cornerstone Contributions: Muster at High Tide: The June 30th Muster Roll of the Petersburg Old Grays, Co. B, 12th Virginia Infantry

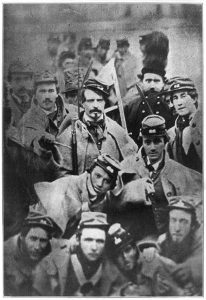

The American Civil War has often been described as a “rich man’s war – poor man’s fight”, a perspective borne out by disproportionate suffering of the lower and middle-class compared to an educated, wealthy elite. Wealth frequently allowed men the ability to buy their way out of service by hiring a substitute or to be exempted from service in the South by owning more than twenty slaves. Most regiments, both north and south, were filled with poorer farmers or industrial laborers. As the war drew on, and the armies more hungry for soldiers, more and more farms and factories were emptied of their labor to feed the blood baths that were Antietam, Cold Harbor, Chickamauga, and many more battles. Many were conscripts, immigrants who stepped off the boat and into a foreign war, or volunteers who simply had no other choice but to fight. The 12th Virginia Regiment of Virginia Infantry was a bit different.

Perhaps we should start with “what is a regiment?” Regiments were organization units within an army. In order to defend the newly formed Confederacy in 1861 several armies were formed, including the well-known Army of Northern Virginia. An army consisted of two to four corps, which were made up of two to four divisions. A division likewise consisted of two to four brigades, each of which included four regiments. A regiment ideally contained one thousand men and was broken into ten companies. While each of these units within an army was important, the real soul of an army was the company. A regiment, such as the 12th Virginia, consisted largely of men from the Petersburg area but it wasn’t uncommon for a regiment to include companies from far flung areas of the state. For example, the 23rd Virginia Infantry included men from Goochland, Louisa, Charlotte, Richmond, Prince Edward, and Halifax counties. However, within each company was a community. Companies were often formed from local militias and represented a locality. The men within a company had grown up together, and during the Civil War, suffered and died together.

We discussed organizing an army from the top down in the blog about the seal of the Adjutant and Inspector General of the Confederate States Army (https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/news/corner-stone-contributions-the-seal-of-the-office-of-the-adjutant-and-inspector-generals-office-csa/). Now let’s move to how an army was also organized from the bottom up. Every few months a company was mustered for inspection, condition, strength, and composition. A form called a muster roll was filled out and certified to be accurate by the company’s commanding officer, either a captain or lieutenant, and certified by an inspecting officer. These periodic inspections were critical for army brass (officers). Without muster rolls, General Lee and his command would have been blind as to the strength of their forces.

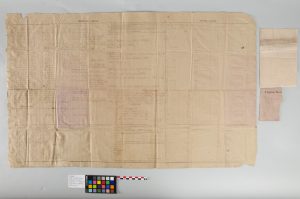

Contained within the copper box placed below the Lee Monument was a muster roll of the 12th Virginia, Company B, known as the “Petersburg Grays”. Companies often carried a nickname that referenced their locality such as the “Riverton Invincibles” (10th Va. Inf. Co. I), “Grayson Dare Devils” (4th Va. Inf., Co. F), or the “Richmond Light Infantry Blues” (1st Va. Inf., Co. E).

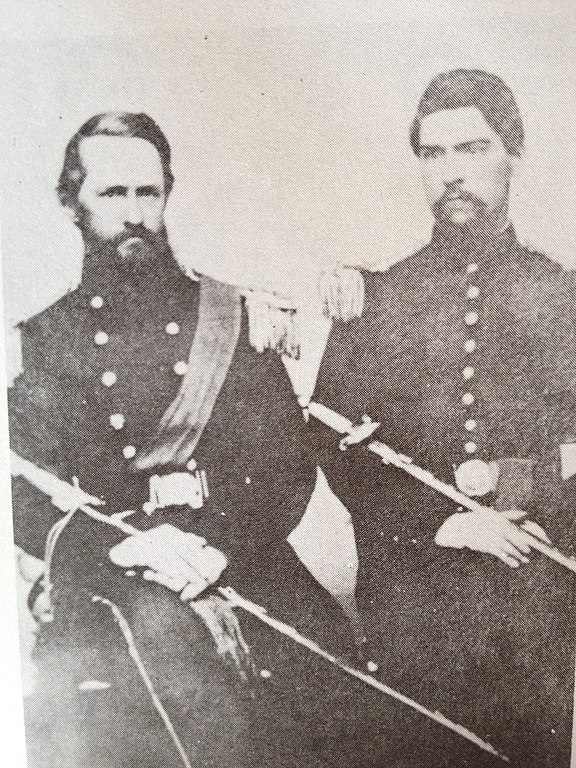

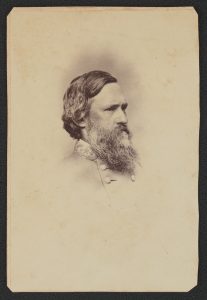

The Petersburg Grays were an old militia company first mustered in 1828 and fought in the Mexican War during the 1840s. In 1859, the Petersburg Grays were dispatched to Charlestown, Virginia (now West Virginia) for the hanging of John Brown. Colonel David Addison Weisiger, who signed this muster roll, served as the Officer of the Day to preside over the hanging. According to eyewitness David Hunter Strother, the troops stood “mute and motionless” for half an hour while Brown’s body silently dangled from the noose. It was their job to witness for the nation “the awful majesty of the law.” (Stutler 1955).

In May of 1861, the Petersburg Grays became Co. B of the 12th Virginia Regiment of Volunteer Infantry for the Confederacy. During the organization, the Petersburg Grays swelled in numbers and a new company (Co. C) was split off to become the Petersburg New Grays, Co. B now became known as the Petersburg Old Grays. Formed in Norfolk, the regiment consisted of six companies from Petersburg with the remaining four coming from across Southside Virginia. They were collectively known as the Petersburg Battalion. The 12th Virginia was combined with the 6th, 16th, 41st, and ultimately the 61st Virginia regiments under the direction of General William Mahone to form Mahone’s Brigade.

Fortunately for General Mahone’s command, the first year of the war was quiet and their main action was the taking of Gosport Navy Yard, a critical success for the formation of any Confederate naval force. That all changed at 5:30pm on July 1, 1862 at the Battle of Malvern Hill. Mahone’s Brigade was swept up into a charge across open ground. Federal sharpshooters intentionally withdrew to clear the field for a withering artillery barrage. The 12th, and other units were caught in the open and pounded with canister shot. Each cannon was turned into a large shotgun and the result “was not war – it was murder.”, according to the General D. H. Hill, who was ordered to lead the charge,

The very next month, at the Second Battle of Bull Run/Manassas, General Mahone was wounded in heavy fighting and the 12th Virginia saw brutal combat once more. With no time to recover, the regiment marched north with the Sharpsburg Campaign in September of 1862. At the Battle of Crampton’s Gap on September 14, 1862 the 12th Virginia lost 60 men. By this time, combat, sickness, and fatigue had taken a ghastly toll on the Petersburg Old Grays and when the unit was thrown into battle at what became known as “Bloody Lane”, the regiment fielded only 23 men. The campaign to and from Antietam took a huge toll on the Army of Northern Virginia. My own great-great-great grandfather, then an Assistant Surgeon with the 32nd Virginia, remarked from this campaign “men could have been tracked for miles by blood from their feet.” Hunger was rampant and men became desperate for food and water. Less than three months after Antietam, the remains of the 12th Virginia held the Confederate line at Fredericksburg. Thus, they ended 1862 with a major Confederate victory but at a terrible cost.

Spring brought additional loss to the 12th Virginia. At Chancellorsville, the regiment lost 36 by death or wounding with an additional 51 prisoners taken. By then, desertion stalked the ranks and muster rolls from late in the season show that nearly two-thirds of the regiment was absent without leave. Most historians would explain such a desertion rate in the spring as a temporary loss suffered by the army as soldiers returned to their farms to plant crops, but the 12th Virginia was uncharacteristically urban.

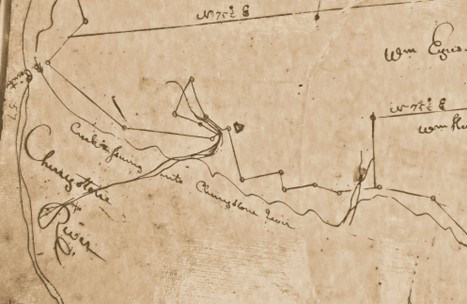

When the muster roll found in the Lee cornerstone box was taken on June 30, 1863, the men present were unaware that the tide of the war was only days from turning. It was a Tuesday and General Meade, the newest commander of the Army of the Potomac, stalked western Maryland to “find and fight” General Lee. The Petersburg Old Grays remained at Fayetteville, Pennsylvania about eighteen miles west of a quiet town named Gettysburg. It was “the most delightful camp which I remember during the war” according to Westwood Todd (1888), a private in the 12th Virginia.

Mahone’s Brigade, then part of Anderson’s Division, broke camp early on July 1, 1863 and marched eastward to join the Army of Northern Virginia. While the battle of Gettysburg would mark the high tide of the Confederacy, as defined by the repulse of Pickett’s charge, Mahone’s Brigade stood by in reserve and watched. General Mahone’s decision to remain in reserve was confusing as more battle-weary regiments were thrown into brutal combat. However, reorganization of the Confederate officer corps had led to communication breakdowns that may have contributed to one of Lee’s most hard-hitting commanders keeping his brigade on the bench.

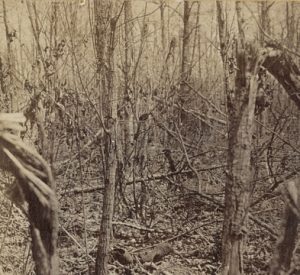

The year of 1864 saw the 12th Virginia at the Battle of the Wilderness as part of their opposition to General Grant’s Overland Campaign. The battle, fought through a large, densely thicketed region, resulted in more than one case of friendly fire. When Mahone’s Brigade entered a chaotic scene where lines and sides were crossed, he halted the troops. The 12th Virginia under Colonel Weisiger crashed on through the underbrush. Realizing he was well in advance of the brigade line, the 12th turned around and reversed direction. General Longstreet, attempting to reconnoiter the melee, became accidentally trapped between the lines as the 12th Virginia ran into the 41st Virginia. Sporadic, nervous fire from both sides increased to full volleys and Longstreet was shot through the neck and upper back. When the smoke cleared, not only was Longstreet badly wounded, but several soldiers from the 12th lay dead.

As the year drew on, the war settled on Petersburg, home to many of the 12th Virginia, and nearly all of the Petersburg Old Grays. General Grant placed the might and power of the U.S. Army on the city and began the final siege of the war. From June 18, 1864 until April of 1865 the regiment was largely entrenched at Petersburg. The Battle of the Crater, an attempt by the U.S. Army to blow a hole in the Confederate defenses, was Mahone’s Brigade’s last notable action in major combat. When 320 kegs of gunpowder blew up beneath the Confederate line in the early hours of July 30, 1864, more than two hundred soldiers were immediately killed. A giant hole, ripped open from the earth, smoked, and steamed. For about an hour the confusion slowly abated and then General Mahone led a counterattack. What resulted was one of the most futile and gory battles of the war. Its result was tactically meaningless and more than 800 soldiers died. U.S. Colored Troops who took part in the U.S. advance were targeted by Confederates and even Mahone had trouble stopping the bloody reprisal.

When Petersburg fell in the spring of 1865, Mahone and the 12th Virginia moved westward on what would become Lee’s Retreat, or the Appomattox Campaign. Mahone’s men guarded the crossing of the Appomattox at Goode’s Bridge before joining what was left of the Army of Northern Virginia on its march towards Lynchburg. After numerous ankle-biting skirmishes between the two armies and a major engagement at Sailor’s Creek where Lee lost one-fifth of his army, the Petersburg Regiment surrendered a total of sixteen officers and 180 men at Appomattox.

Mahone’s Brigade is unique in that it remained intact throughout the war. The 12th Virginia, the Petersburg Regiment, was remarkable since it was one of the most urban units in the Confederacy. It was also one of the most well educated. More men in the 12th had some form of formal education than in most other units. Today, we may easily fail to see Petersburg for the thriving urban center it once was. The “Cockade City”, as it was known, was once the southern literary and theatre capital. The 12th Virginia was its own regiment and so we return to the concept of a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight. The regiment took its share of body blows during the war, was never favored for being a bunch of rich ‘city boys’, and even included a number of farm lads from Meherrin and Brunswick. Like many units, the ranks swelled and, more often, dwindled but the unit persisted.

So why a muster roll for the Lee container? Why this muster roll? What is the importance? There are likely three parts to this answer. First, a muster roll is a snapshot of a unit’s composition and health. Comparing rolls over time within a unit, we can see how a portion of the army reacts to the war and the sentiments of the people. In this muster roll, while much of the text is barely visible, we can see that many men were listed as “absent sick”. A few were “absent without leave” (AWOL), and several were detailed to hospital or other duties. Was some of this favoritism for the rich boys? Maybe, but most regiments were drawn from to support the needs of the army in general. It is more likely here that the higher degree of literacy or mathematical aptitude led the 12th Virginia to poaching by army brass. I believe this muster roll was in part placed in the copper box beneath statue as a monument to the men of the 12th Virginia. This form of recognition, in itself, is not an uncommon way to put a few names of the “common man” in a silent place to share the intended grandeur of the booted and spurred bronze hero, Lee.

The second part of the answer is purely conjectural, but bears a moment of contemplation. When Captain T. A. Brander, former artillery commander under W. J. Pegram, placed the muster roll in the box, he did so not only as a principle driver in the monument’s construction. The symbolic date of the muster roll must not be ignored, being the last muster of the Petersburg Regiment prior to Gettysburg. The bucolic encampment at Fayetteville, Pennsylvania, only moments before Lee’s crushing defeat, represents a time that Faulkner (1948) put so well:

“It’s all now you see. Yesterday won’t be over until tomorrow and tomorrow began ten thousand years ago. For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it’s all in the balance, it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet, it not only hadn’t begun yet…but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and those circumstances which made more men than Garnett and Kemper and Armistead and Wilcox look grave yet it’s going to begin, we all know that, we have come too far with too much at stake and that moment doesn’t even need a fourteen-year-old boy to think This time.”

The third part to the answer is what some members of the 12th Virginia and Mahone’s Brigade did after the war. The uncharacteristically educated regiment played a big part in the Readjuster movement. This complex political party crossed many traditional boundaries, including race and sought to refinance the state debt in order to establish a system of public education. They ‘readjusted’ war debt owed to northern creditors and leveraged it to create such things as the Virginia Polytechnic Institute, now Virginia Tech. Under the party, poll taxes and public whippings were eliminated. Mahone led the movement and a number of veterans from the 12th Virginia joined him. The Readjuster movement was over as soon as it began but likely had more progressive effect on the state than any single point of post-war influence. No one knows Captain Brander’s feelings towards the Readjusters, and by the time the copper box was placed beneath the Lee Monument cornerstone in 1887, the movement had lost power five years prior. But, of all of the single Civil War units, perhaps the 12th Virginia had the most positive effect in the years following the war.

The faded paper, ink, and pencil of the muster roll are indeed a snapshot. It is a powerfully nostalgic glimpse into that sunny afternoon of June 30, 1863 and into a Virginia that struggled to be post-Confederate. Some of the men of the 12th Virginia sought to put the Commonwealth back together and move forward in a way that they saw as the only way to prevent plunging “over the world’s roaring rim.”

— Brendan Burke

Underwater Archaeologist

Division of State Archaeology

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR’s archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

Campbell, Eric A.

2010 Sacrificed to the Bad Management of Others; Richard H. Anderson’s Division at the Battle of Gettysburg. National Park Service Gettysburg Symposium: The Army of Northern Virginia in the Gettysburg Campaign. Gettysburg, PA.

Faulkner, William

1948 Intruder in the Dust. Random House. New York, NY.

Stutler, Boyd B.

1955 “An Eyewitness Describes the Hanging of John Brown.” American Heritage. Vol. 6, Issue 2.

Todd, Westwood

1882 Reminiscences. Unpublished manuscript. University of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC. Accessed online on 11MAY2022 at https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/00722/#folder_1#1