Batteau Classroom: Studying the James River with VCU’s Footprints on the James Class

DHR’s State Underwater Archaeologist Brendan Burke reflects on his experience teaching and learning about the history and ecology of the James River with students in Virginia Commonwealth University’s (VCU) Footprints on the James, an annual monthlong field program that uses the river as a modern classroom for environmental and cultural study.

Written by Brendan Burke | DHR State Underwater Archaeologist

Photographs by James Vonesh, Ph.D./2024

A sudden change in facial expression, perhaps a shift in posture, or even a jolting increase in volume of voice may betray the spark of learning in a student. Whether outwardly expressed or quickly tamped down, the spark is immediately recognizable to the teacher. For a professor, it is pure gold. It is their raison d'être. For over a decade, VCU’s Footprints on the James (FOTJ) program has accomplished this for students for an entire month each year. Offered as a collaboration between the university’s Biology Department, the Center for Environmental Studies, and the Outdoor Adventure Program (OAP), the class is a four-week adventure in learning on—and within—the James River.

In FOTJ, students from all walks of life experience the James in its biological and cultural intricacies, expedition style. Paddling sea kayaks from Ancarrow's Landing to the mouth of the Chickahominy, they learn about the river by examining water quality, invertebrate communities, and crustaceans. They walk in the steps of thousands of years of human occupation along the river’s upper tidal reach. At night, sleeping under the stars brings students close to nature (perhaps too close if the mosquitoes are active). The class then moves upriver to study the falls. It is here where students learn to respect the power of water. Helmeted and trained in basic water safety, they navigate Richmond’s blue-ribbon whitewater and learn about the importance of waterpower in the city’s formation and history.

Based at the VCU Rice Rivers Center in Charles City County, FOTJ mainly involves traveling the watershed to experience nature up close. Days begin at sunrise and often end late at night by the campfire or with flashlights, in planned sessions where students give updates on their projects. I wasn’t prepared for the variety and depth of the students’ scientifically piercing questions. Clearly, some of these students are bound for greatness and the crucible of the FOTJ program helps them hone their edge. For those who were not as invested in biology, FOTJ was inspiring in a way that helps anyone find more clarity in a confusing and confounding world.

My journey as a student of nature began 34 years ago, when I first raised my hand as an aspirant Boy Scout in Troop 443, which was housed in the basement of First Baptist Church. With a dedicated group of leaders, over the years we froze to pieces at Ramsay’s Draft in the winter, hiked until we dropped on the Appalachian Trail, and canoed the whitewater cataracts of the Flint River in Georgia. We also spent a lot of time on the James River. Every moment was the quintessential investment in each of our futures, and it left an impact. One of the older scouts was a young man named Daniel Carr. I moved from Richmond at a young age, after which Dan and I parted company—until last year. As luck would have it, we both presented at the Middle James River Roundtable, a multidisciplinary event hosted to highlight the challenges facing the James River both past and present. Dan introduced me to the FOTJ faculty and explained how I could contribute to the curriculum. Outreach is a central part of DHR’S Division of State Archaeology, plus I was on a mission to locate a reported historic batteau wreck along the class’s planned route. A few short months later, it was game on.

On June 10, I met the class at James River State Park. For the next few days, the students followed the river through its water gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains below the town of Glasgow. They learned about the geology of the region along the river, which cuts through the mountains, and navigated the cataracts at Balcony Falls. Weary from hauling the canoes and camping gear from one site to the next, the group seemed to recharge at the new setting and the prospect of traveling aboard a traditional James River batteau. That evening, after the kitchen-patrol crew finished cleaning up the chow line, students learned the art of starting a fire. They then coalesced around a lantern to share results of their ongoing research. Despite the long day and late night, there were no flimsy questions or drooping eyelids. By 11 p.m., we all dispersed to our tents to prepare for the next day.

Stretching 43.5 feet in length, the batteau named Mary Ingles was moored to a tree root arching out of the muddy bank. Its captain and crew had trailered it to the park the previous night. It would serve as the mothership for the class. Our mission was to reach the town of Scottsville, located 32 miles downstream, in two days. At the time, Central Virginia was entering the second early summer drought in two years and the water levels were low. Getting Mary Ingles, a wooden behemoth, downstream would take every bit of river knowledge and physical strength.

Mary Ingles is patterned after Boat 28, which was excavated in 1983 during the Great Turning Basin dig along the James River in Richmond. Mary Ingles is a faithful replica of Boat 28, which hails from the halcyon days of river navigation in the Upper James, as described in detail in maritime historian archaeologist Bruce Terrell’s 1992 thesis. Mary Ingles’ owner Andrew Shaw and her builders Kevin Ferrell and Sebastian Backstrom were recipients of a National Geographic Young Explorers award. They used the funds from the award to build and pole a batteau up—yes, up—the James River to retrace the steps of the Marshall Expedition of 1813. For the last five years, the trio have contributed their time and expertise to FOTJ so that students can experience the river in a historic and unique way.

Not long after getting our flotilla underway, students aboard Mary Ingles were taking lessons in poling. While it may seem simple, managing three people on each side of the batteau to handle 20-feet-long wooden poles in unison requires practice. After some scuffling, a unified crew emerged, and a bow wake formed beneath the stem. Not long downstream, we came across our first obstacle. Ahead were the remains of the Tye River Dam, a structure made of stone and wood that had been an archrival to batteaux plying the river.

The Tye River Dam was built to back up a pool in the river and divert water into the James River & Kanawha Canal on the north bank. Periodic dams like these were the primary method of ‘watering’ the canal. They also spared workers from having to dig a continuous canal bed adjacent to the river. The backed-up water, which was allowed to run over the top of the dam, slowed down to permit ‘slack water navigation’ along the riverbank. A bankside towpath allowed draft animals to pull heavy cargo boats and packets up the river and into the next segment of the canal. When the canal was abandoned in the late 19th century, the dam was harvested for its cut stone and the river returned to its natural level. Today, the dam hardly seems like the mammoth structure it once was. From upriver, it appears as merely a shelf in the river. On the south side of the dam footers, sufficient water passes over the dam in an easy Class II rapid that most kayakers and canoeists revel in. As we approached the dam’s remains, Kevin cautioned the students that even small rapids can quickly become Class V rapids for a batteau. If a boat gets caught sideways on rocks, its sheer size makes it particularly susceptible to being torn apart by the power of the river. With poles at the ready, and eyes scanning the water for ‘sleepers’ and big rocks too close to the surface, we sped through, only bumping a couple of smaller rocks.

As though the slalom was complete, Kevin and Sebastian piloted the boat for the right bank and gave the command to man the poles and make headway. A natural rock shelf angles across the river below the Tye River Dam and there is only one way through. A historic sluice, carved into the south bank centuries ago, still provides enough water to allow modern batteau replicas to circumvent the rock shoals. From a distance it didn’t look like much of a gap and, as we came closer, the tiny channel and low water made the passage a technical accomplishment even for a canoe. Again, our pilots picked their way through the sluice, and we shot out the other end. It was a feat of control over the batteau and quite one to witness.

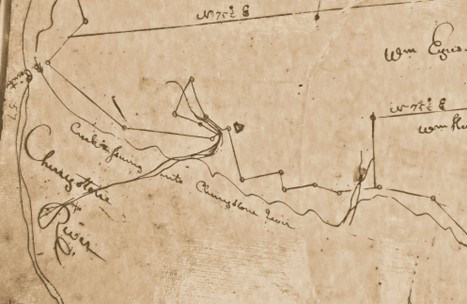

Below the sluice we slowed to the river’s drowsy current and shifted our gaze to the southern bank. A year ago, the remains of a wooden vessel at this location were reported to DHR’s Underwater Archaeology team. My team had deployed to the spot last year but ran out of time to fully survey the area. This time, the opportunity to search for the wreck from a replica batteau was thrilling. And, as luck would have it—just beyond where last year’s search had ended—the group spotted the wreck! Long fingers of wood, all geometrically arranged, seemed to emerge from the muddy bank. Beneath them, the flat planks of a vessel’s bottom betrayed this tangle of wood from the natural tree trunks and roots of the river.

The flotilla was drawn together, and I hopped into the water to inspect the site with other students. We took some basic measurements. Afterwards, waist-deep in the waters of the James River, the students and I discussed the historic artifact before them. Is there a better way to learn about James River Batteaux than while floating on a replica next to an original? This was an extraordinary moment for the students in the course. They discussed how their interaction with archaeological practice and historical artifacts during this experience deepened their connection with the river and broadened their appreciation for interdisciplinary science.

For the next two days, the students collected zooplankton, recorded bat calls, and learned how to read a river. In the slower moments the students reflected on how the river has shaped the lives of so many people who have lived alongside it, who have worked in it, or otherwise harnessed its power for industry. They learned about the natural world while floating on its waters. On the final day of the FOTJ class, students presented the findings of their research projects in a ‘floating symposium’. With Mary Ingles as the main stage, each team’s representative stood atop the deck box and defended their ideas and fielded questions.

My FOTJ experience came to an end all too soon, and I departed the class at Scottsville for Richmond. Dr. James Vonesh, Professor Daniel Carr, and the students of the Outdoor Adventure Program work hard to bring this pedagogical model to fruition. Its success is measured in the program’s longevity, the dedication of returning staff, and in the experiences of the students. Additionally, the model of FOTJ has been expanded to include courses on rivers in Idaho, Texas, South Africa, and Mexico. These are collaborative experiential field courses offered through VCU in connection with the River Field Studies Network. The opportunity to contribute to the cultural context of the FOTJ program was a treat and, to be honest, I may have learned more than I imparted. The cultural patrimony of the James River is an invaluable asset to all Virginians and our guests. DHR’s role in stewarding, preserving, and sharing the river fits naturally within the FOTJ model and we are honored to have been included.

References:

Terrell, Bruce. "Tobacco Transport in Upland Virginia 1745-1840." East Carolina University Research Report No. 7. The Program in Maritime Studies. East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, 1992.

"Footprints on the James continues to make a deep impression on VCU students," Virginia Commonwealth University, access July 2024, https://vcu.exposure.co/footprints-on-the-james-continues-to-make-a-deep-impression-on-vcu-students?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR2A4YSOEit3lFXGOKlyjs-F0G-c7ajWVV8OTheWbAtG5GTQ8W54R-57Of4_aem__3qTXXl-EYxghz2-bJfyPw.