Sudden and Horrifying: The Vauxhall Chain Bridge Disaster

More than 150 years after tragedy struck in Richmond, underwater archaeologists search the murky waters of the James River for traces of the infamous event that recalls an unprecedented moment in Virginia’s political history.

By Brendan Burke, State Underwater Archaeologist

Setting the Stage - Islands in the Stream

There is no doubt that the study of underwater archaeology can take us to many places. From deep Atlantic waters to shallow mountain rivers, seeking history beneath rippling waters and rolling seas puts us in contact with just about every type of human story. This story is about a place of historic political importance in Virginia—a place that’s nearly within sight of Capitol Square yet almost invisible. It’s in the heart of downtown, yet frequented mostly by fish, racoons, and the occasional heron. Yet, the story was once the talk of Richmond, and a tragedy known far and wide.

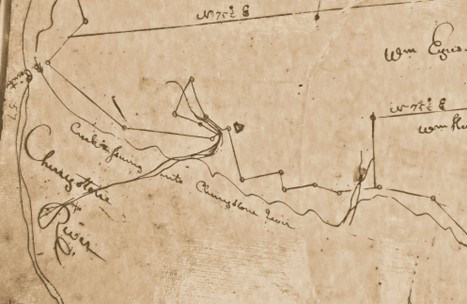

The Falls of the James River is a series of wild and rocky cataracts where the river changes from a brisk upland river to a slower, wider channel winding eastward through the coastal plain. Mayo Island, one of the largest islands in the Falls, has long hosted human habitation and industry as well as one of the oldest crossing places connecting downtown Richmond with Manchester on the south bank. The waters of the river here are confused. Fresh water tumbling out of Pipeline Rapids; the Devil’s Kitchen feeds into brackish water heaving up and down, twice daily, with the tides. Mayo Island may as well have its head in the upland and its feet in the tidewater. It also anchors an area known as the Archipelago of the James. Several large, multi-acre islands and hundreds of rocks form a geological parapet through which the river rushes. Most of the larger islands have names that few now know, least of all Vauxhall Island.

Properly pronounced ‘fox-hall’, Vauxhall Island’s name came from the Old Dominion convention of appropriating English placenames for its own use. Vauxhall Gardens was a sculpted public space in London known for its beauty and as a place for leisure. In Richmond, Vauxhall Island—also known as Vauxhall’s Island—was a convenient place accessed from a side-spur off Mayo’s Bridge. As early as the 1840s, Vauxhall Island was frequent host to cockfights. By mid-century, a saloon and shuffleboard hall were popular destinations for Richmonders seeking recreation and libation. A smaller island upstream offered an open field frequented by the city’s Young Militia, by the city police force for barbecues, and even by the Turnverein, a troupe of Germanic dancers. Today, that island is known as Bailey’s Island, but during the 19th century it went by the sobriquets Kitchen Island and Barbeque Island. To access Kitchen Island, visitors must cross a wood-and-chain suspension bridge that spanned the shallow, rocky channel from Vauxhall Island. While the bridge’s builder and the year it was built remain unknown, most 19th-century Richmonders would have been familiar with the recreational and salubrious atmosphere of the Vauxhall/Kitchen Island complex. They would have known the chain bridge.

Barbeque Battlegrounds

Lee’s surrender at Appomattox is a typical bookend to the American Civil War (1861-1865), and for the most part, the war ground to a halt. No matter the side, men and women throughout the country were weary from the four years of fighting, killing, and destruction. Richmond was in ruins and hundreds of farms, factories, and mills throughout the South were relegated to empty fields strewn with human bones and smoking rubble. Reestablishing the Union was a new struggle that set up a number of political battles throughout the American South. Not surprisingly, factions in both the North and South sought retribution for atrocities perceived and real. Others, including President Lincoln, recognized that retribution and healing were incongruous. With a single bullet, John Wilkes Booth derailed Lincoln’s push for a more gentle reconstruction. After the president’s murder, concepts of retribution were unleashed on states formerly in rebellion. Not surprisingly, there was a backlash.

Virginia’s Reconstruction was, compared to other Southern states, relatively painless. A state constitutional convention was convened in 1867 to reset governance within the Commonwealth. Its two singular achievements were enfranchisement of Black men and the establishment of free public schools. Known as the Underwood Constitution, these bold acts upset Virginia’s pre-war political establishment. The new constitution was drafted by a faction of the Republican Party known as the Radicals. Radical Republicans sought punitive actions to punish former Confederates by barring them from public office and by attempting to integrate schools and other public institutions. Having pushed the pendulum far over, Radical Republicans encountered fierce resistance within the party by an organized faction known as the True Republicans.

In 1869, True Republicans assembled a slate of candidates designed to sweep the state. Election day was set for July 6, and issues on the ballot included the selection of a new provisional governor; ratification of the Underwood Constitution; attendant clauses to the constitution designed to extirpate former Confederates from any power; and the selection of a new senate and delegates for the General Assembly. The Radical Republicans fielded H. H. Wells for governor while the True Republicans stood up Gilbert Walker. A native of Binghamton, New York, Walker established a coterie of former Confederates to seal his establishment feel. Realizing that new political mathematics necessitated winning a portion of the Black vote, Walker and his team courted Black communities. However, the True Republicans lacked elements of the pre-war political establishment and the White social elite—they needed local help.

Fed up with the 1867 wins by Radical Republicans, a group of well-heeled White Virginians cobbled together a new party. Comprised of former Democrats and Whigs, the new Conservative Party outright opposed many of the provisions in the Underwood Constitution, especially enfranchisement of African American men. Conservatives aligned with Gilbert Walker’s True Republicans, and with that, achieved a segment of the voting Black population.

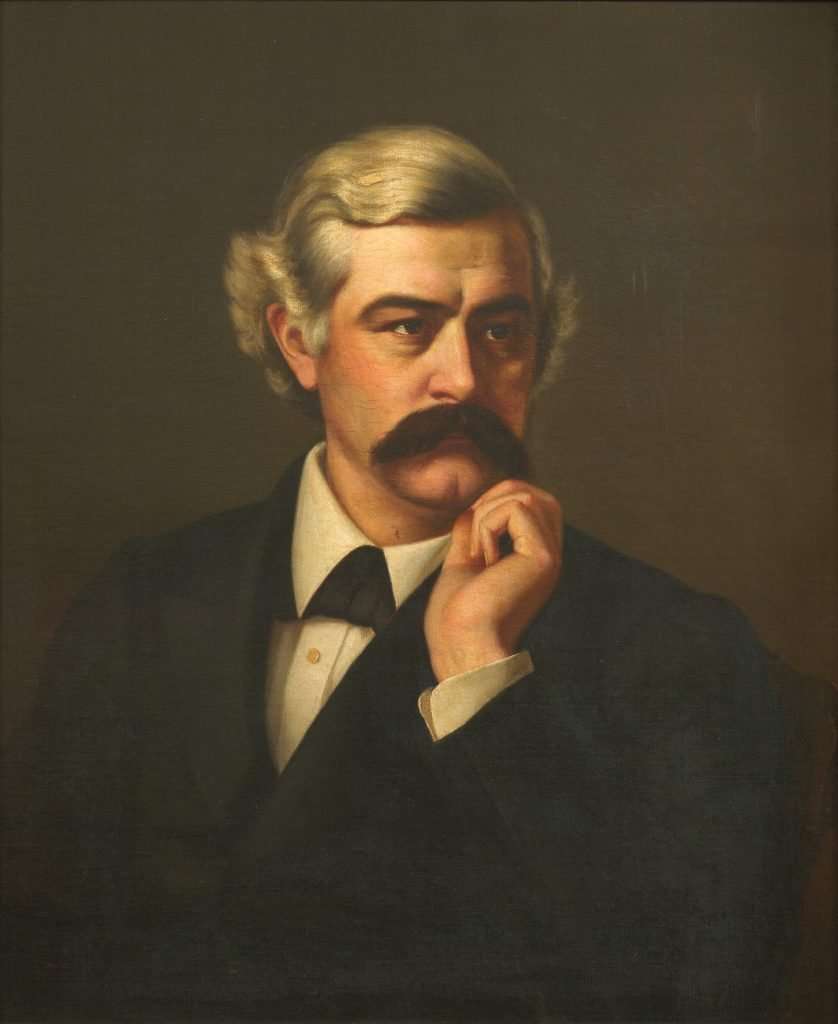

James Read Branch, Secretary of the Conservative Party, was an unknown entity amongst the party and one of the few founding members without prior public service. Born into a banking family, Branch served as an artillery officer during the Civil War in the Army of Northern Virginia. After the war, he returned to finance and established himself in the Richmond finance scene. Col. Branch, as he was known, was seen as a safe and effective candidate for Virginia Senate. Free of pre-war political baggage, Branch was one of the few Conservatives who admitted they needed some of the Black vote to win. Party operatives worked Richmond’s African American community and billed the alignment of the Black and White vote as a “coming together of the white people of Virginia and the colored people who have been estranged through the agenda of the devil.”[1]

Thomas Branch, father of Col. Branch, funded a barbecue and political rally on Kitchen Island. Widely advertised in Richmond papers, the event was particularly focused on attracting Black Walkerites, who were seen by many of their peers within the African American community as turncoats. It was a fact that the Conservative Party and True Republicans offered a direct path for some of Virginia’s Black men to rise to political power in the General Assembly. On the morning of Friday, July 2, 1869, fires were lit on the island to cook heaps of food. A band set up and, around noon, started to play. There was a bar with free liquor, a dance, and even a swing for partygoers to enjoy. Event organizer Abram Hall brought a large banner with a white hand shaking a black hand under the words United We Stand, Divided We Fall. The city knew about the event, and throngs of visitors headed to Vauxhall Island to cross the chain bridge into Kitchen Island for the party. Only one thing stood between them and Col. Branch’s campaign offerings: Policeman Thomas Kirkham.

Straining and Straining – The Tragedy Unfolds

English-born Kirkham was a 32-year-old resident of 7th street in Richmond. Gen. Schofield, Virginia’s Reconstruction manager for Uncle Sam, had appointed him to the Richmond Police Department. Officer Kirkham was instructed to guard the chain bridge to Kitchen Island and only allow people with invitations to pass. Few invites had been issued, and by midday, a crowd of frustrated attendees-to-be had assembled. Advertisements for the event billed it as open to all. Feelings of disenfranchisement likely emerged. Word got to Col. Branch, who was hosting on Kitchen Island. Branch promptly walked to the bridge, crossed halfway, and yelled to Officer Kirkham, “Let them come on! Dinner is nearly ready! There is plenty of room!” These were his dying words.

Kirkham stepped aside and people poured onto the bridge. Stout, upright timbers on either side of the river channel supported two large chains. Suspended beneath the chains by wrought iron strapping, a 5-foot-wide footpath carried the increasing weight of its human cargo. When the people reached the center, the bridge began to shudder and buckle. Two of Branch’s associates standing on the bridge near the Kitchen Island abutment heard timbers cracking and ran for safety. With a splintering roar and crash, the bridge collapsed.

Into the rushing current, the yells of men mixed with the grinding of bridge components still in collapse. Two upright timbers on the Vauxhall abutment crushed Officer Kirkham to death. Attendee Robert Lotsey’s thumb was sheared off. John Morris suffered a ‘grievous injury to his loins’. Abraham Hall’s arm was broken, and a score of others suffered bruises, concussions, and even paralysis. In the water, Col. Branch’s head was seen to rise and then submerge, his body caught in the wreckage.[2]

Dudley Powers skipped work at his father’s firm that afternoon to attend the political rally and score a free lunch. The 20-year-old Powers was on the foot bridge to Vauxhall Island when he saw five hats floating in the river below. Immediately recognizing some recent calamity, Powers ran across to Vauxhall Island, attempting to reach the island beyond. Instead, he was greeted by grief and tragedy.

Branch’s body lay on the grass, attended by two men. Powers commandeered the scene, and the three carried Col. Branch into the shuffleboard house and lay him out on a table. An awestruck audience formed around him when Powers observed that Col. Branch had a pulse. Immediately, physicians in attendance took contemporary means to revive him by opening an incision in his scalp. Likely, the concussed Branch needed pumping out, but CPR was not yet part of accepted medical doctrine. The young Powers watched on as attending physicians worked on Col. Branch. Despite their efforts, however, he died.[3]

Col. Branch’s funeral was held at 5 p.m. on July 4, 1869, a Sunday. Mourners packed St. Paul Episcopal Church, causing the vestibule floor to groan. Several flagstones gave way under the crowd, plummeting 20 mourners into the basement.[4] Policemen hurried the wounded off and the funeral began. Patrick Henry Aylett orated an elegy to a funeral that one reporter styled as the ‘largest since that of Stonewall Jackson’[5]. Episcopal Ministers Minnigerode and Duncan read the service. Directors of the Chamber of Commerce, the Merchants Exchange, the Corn and Flour Exchange, and the Tobacco Exchange presented resolutions passed over the weekend in Col. Branch’s honor. Each exchange provided pallbearers for the cortège. Eighty carriages carried mourners while more than 2,000 attendees followed on foot. Despite the grand and solemn affair, not all Richmonders bowed their heads with grief. Verbal insults, even sticks, were hurled from the sidelines as a delegation from the Colored Walker Club followed the hearse to Hollywood Cemetery.

Despite the disaster, Richmond was too electrified by the pending election. Intimidation—as feared on all sides—and nervous excitement carried on through election day on July 6. By midnight, Walkerites and Conservative Republicans cleaned house—a slate of candidates that ushered in a new phase in Virginia’s Reconstruction saga. Years later, Col. Branch’s youngest daughter, Mary Cooke Branch Munford, cited her father’s short political career and unusual tragic death as inspiration for her fight for women’s suffrage and civil rights.

River in the Rain

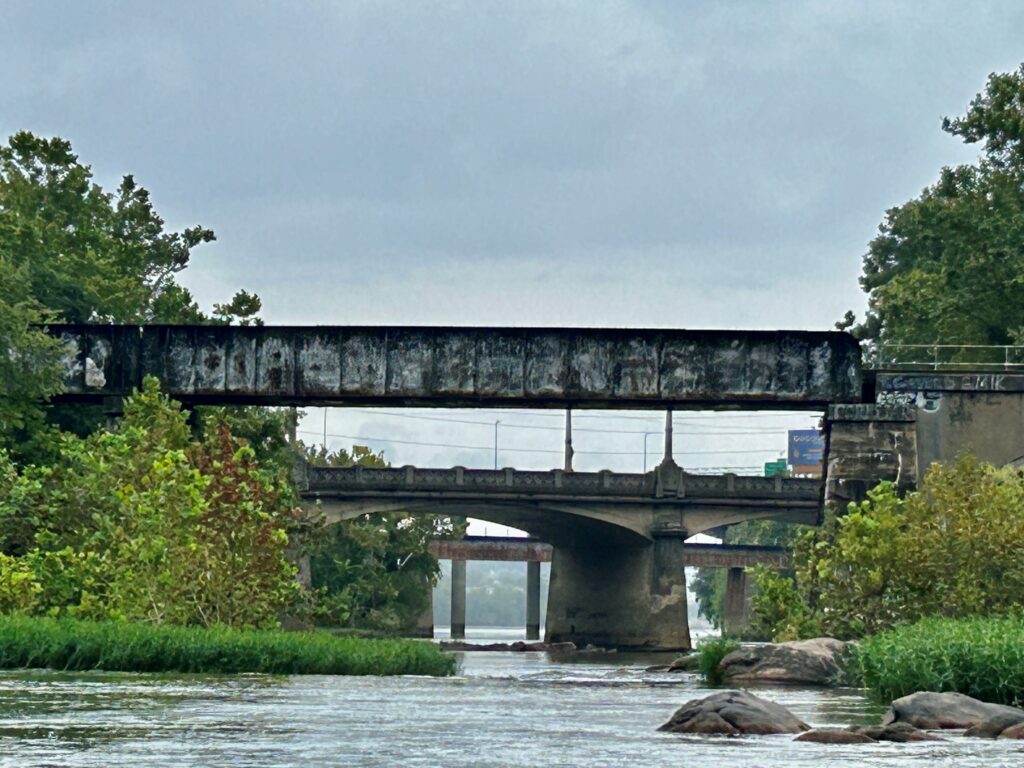

On an overcast Monday morning in August 2023, I met a colleague at the 14th St. takeout to launch our kayaks. The morning workload included addressing citizen reports of unrecorded heritage in the James River archipelago and investigating the historic Mayo's Bridge. The story of Col. Branch was merely a distant tale and one surely without tangible remains. The morning’s agenda took us to the tailrace for a once-giant mill complex, the Haxall Mill. Bricks strewn throughout a river backwater were detritus from Richmond’s burning in April of 1865. As with much of the downtown river, cut and faced stone appear as random scatters and stacks within the water. Concrete foundations, too, indicated a long-abandoned infrastructure. Railroad bridges, power lines, pipelines, trestles, diversion dams, and a built landscape within the archipelago itself provide many layers to the historic cultural fabric of the urban James. The industrial history of the river within the city is mesmerizing.

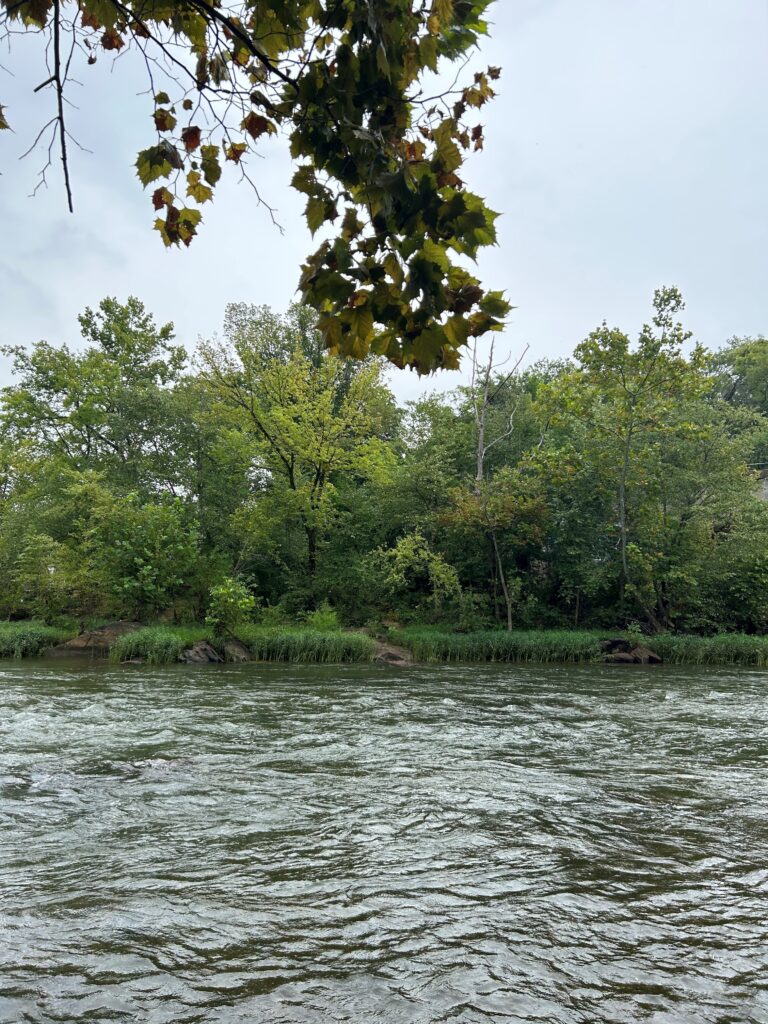

Late morning, with the onset of a drizzle, I suggested that we take a moment to find the place where the chain bridge once connected Vauxhall and Kitchen (now Bailey’s) islands. As we paddled around the south end of Vauxhall Island, six or seven upright timbers appeared in the murky waters of the James. Were these remains of the connector bridge that spanned between Mayo’s Bridge and Vauxhall Island? I was reminded of the Dudley Powers tale, and suddenly realized that this was the spot where witnesses reportedly saw the hats of five disaster victims all those years ago. Sycamore leaves idly floated in the lazy swirl, playing the role. We rowed around the west side of Vauxhall and, powering into the current with our paddles, approached an island to the north.

Scanning river and creek banks is part of my job as an underwater archaeologist. Constant scouring of banklines reveals, and sometimes covers, many sites of historic and prehistoric importance. Learning to read between the leaves, mud, and rocks, is often how we begin to locate a site.

A gnarled Sycamore—common residents of the river’s edge—arched out over the channel. Held in its roots was a cut stone. I paddled closer. More cut stone was discernable within the tangle of roots. Hailing my consort, we landed and inspected the stones. While loosened and tumbled by erosion, the stones formed a large, rectangular mass. The substantial masonry structure was about 12 feet wide and situated right at the water’s edge. I made a joke about finding a section of heavy chain. Seconds later, the two of us looked uphill and into the woods. There, laying on the silty embankment was a three-foot section of heavy, wrought chain. I picked it up. The chain was clearly handmade, with oval links approximately three inches long. The segment of chain disappeared into the sloping bank, solidly anchored to some invisible thing. Scattered nearby were two pieces of wrought-iron strapping with punched holes. Could it be??

Piecing the puzzle together, we realized we had stumbled across the last remaining evidence of the Vauxhall/Kitchen Island foot bridge. While we do not know if the bridge was repaired after the tragedy, these remains provided tangible evidence of one of Richmond’s most famous disasters. Moreover, the tragedy highlights a critical point in Virginia’s political history: where new African American enfranchisement met the adoption of a new state constitution. Several powerful forces sought control of the state as it started a new chapter beyond the recent and bloody Civil War.

Examination of the north end of Vauxhall Island revealed nothing conclusive on the chain bridge. No splintered timbers, cut stone, or broken chain. A fat water snake lay at the water’s edge, holding a catfish in its jaws. While the catfish was dead, its extended spines prevented the snake from swallowing it. The symbolism of the pair was ironic, considering the political struggle of 1869, where two splintered parties held each other in a seeming death grip, and where civic nourishment may have seemed so very far away.

Heavy mist turned to a downpour, and we decided to pack it in. Paddling back, rapids surrendered to pokey tidal water that had receded to expose more cut stone around the takeout. The amount of history contained within—and along—the James River is fascinating and often hidden in plain sight. Each of these resources is a small piece of the historic puzzle, one that we are constantly adding to as we make business and political decisions today that build on our archaeological record. As a giant stone weir, our own material past has become trapped within the river’s Falls—and we continue to contribute to it in our modern and sometimes unfortunate ways. The Vauxhall chain bridge tragedy in Richmond’s political history highlights one such event within the James’s archipelago. The next time you cross the James in Richmond, think of the hidden stories below. Tales of winning and of losing, or triumph and tragedy. Explore the river through its parks and hiking trails, and take in the complexities of nature and culture as they exist between rocks, trees, and rippling water.

•••

About the Author

Brendan Burke is the Underwater Archaeologist with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. As part of the Division of State Archaeology, he works to help discover, preserve, and present the fascinating maritime heritage of the Commonwealth.

•••

Footnotes:

[1] Daily Dispatch. Vol 36 No. 157. July 2, 1869.

[2] Tobacco Planter. Vol. 14 No. 36. October 1869.

[3] Falls of the James Atlas. W. E. Trout, James Moore, and George Rawls. Second Edition. Virginia Canals & Navigations Society. 1995.

[4] Daily Dispatch, Vol. 36, No. 160, 6 July 1869.

[5] Richmond News, 5 July 1869.