The Historic Graves of Buggs Island Lake

The author’s recent visit to the cemeteries around Buggs Island Lake leads to a major revelation about the circumstances surrounding the mid-20th century reservoir’s construction in Mecklenburg County.

By Tim Roberts

Identifying undocumented historic African American cultural resources is my primary job as Community Outreach Coordinator at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR). Cemeteries, alongside churches and schools, loom large among historic resources of great significance to many Black communities. Two weeks ago, DHR cemetery archaeologist, Joanna Green, and I visited five cemeteries around Buggs Island Lake in southern Mecklenburg County. All but one of these cemeteries is associated with historic African American churches. None of them had been recorded in the Virginia Cultural Resource Information System, the commonwealth’s database of historic architecture and archaeological sites.

The cemeteries we visited have something unique in common – they each contain a section where graves have been marked by identical, short, precisely arranged, 6-inch-square concrete posts. Each marker bears a bolted-on plate embossed with the words: GRAVE, FORMERLY GRAVE, and CEM. Every marker is also stamped with corresponding numbers for each of these labels. The word UNKNOWN is embossed above this information on nearly every plate we saw on our trip.

Shiloh Baptist Church was our first stop and the only cemetery we visited on the north side of the lake. We counted approximately 75 markers, all labeled UNKNOWN, in the woods immediately north of the church.

Mt. Ararat Baptist Church’s reinterment section is located just off Highway 15, between the road and the church’s primary cemetery. There are no trees in this cemetery, and the regular placement of the concrete markers is very apparent. An open lane runs through the center of the reinterment section. I suspect there were central lanes through the wooded reinterment sections as well. A more intensive mapping survey of these sites would confirm this possibility.

State Line Cemetery, our third stop, was unique among the others we visited. First, this cemetery contains the remains of white people. Several of the graves are marked with military headstones for Confederate Army veterans. Second, the reinterment section is surrounded by a chain-link fence – which Joanna pointed out encloses a larger area than what appeared to be occupied by the concrete markers – something that suggests the fence may have been erected with the expectation of a certain number of reinterments. Third, this cemetery contained the most plaques inscribed with the names of the deceased, specifically members of the Glasscock, Poole, Claiborne, Wilson, and Seamans families. Fourth, there are two carved stone markers within the enclosed reinterment section. One is illegible, but the other was inscribed for an 8-month-old infant named Hearly Ester Seamans, who died in the summer of 1895. This headstone may have been moved to State Line Cemetery along with the child’s disinterred remains. The distance between the headstone and the footstone is large enough to accommodate an adult burial, suggesting that the grave may have been dug without knowing who was to be buried there; this would have been a reasonable approach considering the hundreds of graves that needed to be relocated in a short period of time from the area being evacuated.

Cedar Grove Baptist Church cemetery’s reinterment section is in the southwest corner of the primary cemetery. Members of the Terry family are reinterred here among the graves of UNKNOWN persons.

The Island Hill Christian Church reinterment section was the largest we visited. A historic frame schoolhouse stands just east of the church parking lot. The wooded area south of the church’s cleared, primary cemetery contains about 450 markers for the graves of UNKNOWN persons. Depressions from many unmarked graves are also apparent in the cleared area.

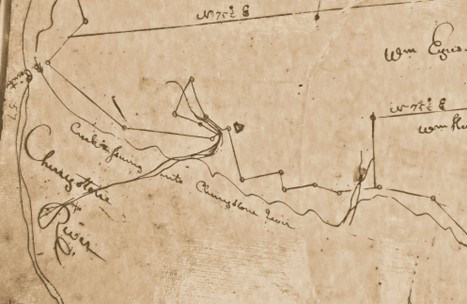

Graves in the reinterment sections of the cemeteries we visited contain the remains of people disinterred from what is now the bed of Buggs Island Lake prior to or during the construction of the reservoir between 1947 and 1952. We’ve been looking for clues on historic maps back at the office.

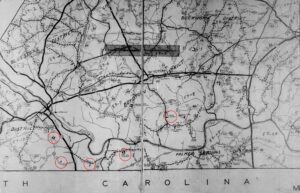

The 1940 census enumeration district map shows buildings and roads within the current lakebed, and an astounding number of churches and schools surrounding the lake. Island Hill appears on the map as IVORY HILL C.H. & SCH.

DHR is working with the United States Army Corps of Engineers to locate records for determining the original locations of the numbered “FORMERLY” cemeteries. We hope this research will bring us closer to reuniting these ancestors with their descendants.

If you have information that may help DHR locate more of these reinterment cemeteries around Buggs Island Lake, please contact me at tim.roberts@dhr.virginia.gov.