State Adds 11 Historic Sites to the Virginia Landmarks Register

—New listings are in the counties of Northampton, Russell, Smyth, Augusta, and King William; in the cities of Charlottesville, Richmond, and Norfolk; and in the towns of New Market and Amherst—

Among 11 places listed today in the Virginia Landmarks Register are a historic district featuring one of the nation’s few remaining pedestrian-only downtown streets, an Eastern Shore estate that includes what experts believe is the oldest colonial site to be excavated on the Delaware-Maryland-Virginia (DELMARVA) peninsula, one of the earliest premier golf resorts in the Shenandoah Valley, and a rare surviving company coal town from the early 20th century.

The commonwealth’s Board of Historic Resources approved the Virginia Landmarks Register (VLR) listings during its quarterly public meeting today. The VLR is the commonwealth’s official list of places of historic, architectural, archaeological, and cultural significance.

Spanning eight city blocks, the Charlottesville Downtown Mall Historic District is a pedestrianized segment of Main Street located at the heart of Charlottesville’s commercial district. The Downtown Mall, which encompasses approximately four acres, signifies an important period in the city’s community planning and development efforts led by elected officials, business leaders, and local citizens in the years following the Second World War. It also exemplifies the work of Lawrence Halprin, a renowned landscape architect of the late 20th century, and his firm, Lawrence Halprin & Associates. Completed in two phases between 1976 and 1980, the Downtown Mall serves as an excellent example of Halprin’s urban design vision to accommodate for movement through space. The Downtown Mall’s design provides for the continuous flow of pedestrians while also incorporating areas for reflection, respite, and social interaction using focal points such as fountains. The only extant work of Halprin in Virginia, the Downtown Mall includes a variety of features, such as brick and granite paving, bosques of deciduous trees, historic fountains and bollards, planters, seating, and public artworks. In 1981, six steel sculptures by University of Virginia artist and professor James Hagan were installed at various locations, adding to the district’s historical significance as an attraction for visitors and shoppers on foot. While 200 downtown streets were pedestrianized across the United States between the 1960s and the 1980s, only about 30 remained pedestrian-only by the end of the 1990s. The Downtown Mall, which was one of those 30, continues to be preserved as the sole pedestrian-only portion of a Main Street in Virginia. Its construction was a turning point for Charlottesville’s commercial success and 20th-century revitalization—one that helps maintain the significant role that Main Street has played in the city’s history for more than 200 years.

Spanning eight city blocks, the Charlottesville Downtown Mall Historic District is a pedestrianized segment of Main Street located at the heart of Charlottesville’s commercial district. The Downtown Mall, which encompasses approximately four acres, signifies an important period in the city’s community planning and development efforts led by elected officials, business leaders, and local citizens in the years following the Second World War. It also exemplifies the work of Lawrence Halprin, a renowned landscape architect of the late 20th century, and his firm, Lawrence Halprin & Associates. Completed in two phases between 1976 and 1980, the Downtown Mall serves as an excellent example of Halprin’s urban design vision to accommodate for movement through space. The Downtown Mall’s design provides for the continuous flow of pedestrians while also incorporating areas for reflection, respite, and social interaction using focal points such as fountains. The only extant work of Halprin in Virginia, the Downtown Mall includes a variety of features, such as brick and granite paving, bosques of deciduous trees, historic fountains and bollards, planters, seating, and public artworks. In 1981, six steel sculptures by University of Virginia artist and professor James Hagan were installed at various locations, adding to the district’s historical significance as an attraction for visitors and shoppers on foot. While 200 downtown streets were pedestrianized across the United States between the 1960s and the 1980s, only about 30 remained pedestrian-only by the end of the 1990s. The Downtown Mall, which was one of those 30, continues to be preserved as the sole pedestrian-only portion of a Main Street in Virginia. Its construction was a turning point for Charlottesville’s commercial success and 20th-century revitalization—one that helps maintain the significant role that Main Street has played in the city’s history for more than 200 years.

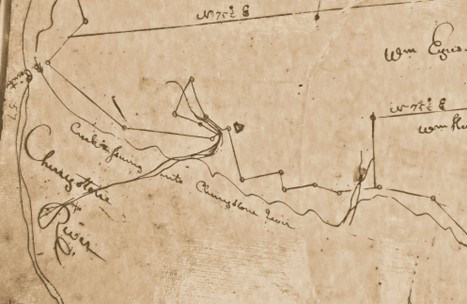

In the Eastern Shore county of Northampton, the bayside estate of Eyreville sits on the west side of U.S. Route 13, occupying a flat neck of land that extends into Cherrystone Inlet, which opens onto the Chesapeake Bay. The 6.5-acre property includes the main historic dwelling, several outbuildings, an ornamental garden, and a recorded multicomponent archaeological site, which experts in Virginia believe is the oldest colonial site to be excavated on the DELMARVA peninsula to date. The Eyreville estate revolves around a two-and-a-half-story brick mansion featuring three distinct sections built in 1800, 1806, and 1839. While the dwelling was initially completed in 1800 in the Federal architectural style for one of its owners, William L. Eyre, Greek Revival- and Colonial Revival-style additions and alterations were added in later decades.

In the Eastern Shore county of Northampton, the bayside estate of Eyreville sits on the west side of U.S. Route 13, occupying a flat neck of land that extends into Cherrystone Inlet, which opens onto the Chesapeake Bay. The 6.5-acre property includes the main historic dwelling, several outbuildings, an ornamental garden, and a recorded multicomponent archaeological site, which experts in Virginia believe is the oldest colonial site to be excavated on the DELMARVA peninsula to date. The Eyreville estate revolves around a two-and-a-half-story brick mansion featuring three distinct sections built in 1800, 1806, and 1839. While the dwelling was initially completed in 1800 in the Federal architectural style for one of its owners, William L. Eyre, Greek Revival- and Colonial Revival-style additions and alterations were added in later decades.

Documentary and archaeological evidence reveals English colonists may have settled at Eyreville as early as ca. 1623, but the first recorded occupation dates to 1637, when the first English colonist associated with the property, John Howe (ca. 1594-ca. 1638), patented the land. From the 17th and 18th centuries to the turn of the 20th century, Eyreville was owned by families of high social, economic, and political standing, including the Kendalls and the Eyres. In 1942, Eyreville was acquired by Guy L. Webster (1885-1976), who owned one of the largest canning businesses in the nation during the mid-20th century. Webster, who used Eyreville as a private home and social space for entertaining guests, made upgrades to the mansion, including a rear colonnade that connected to an indoor swimming pool, and added many surrounding outbuildings as well as a formal garden. Ongoing archaeological work suggests Eyreville possesses the potential to yield additional sites, features, and artifacts that could further inform the study of early Chesapeake society, trade relations between the colonies and Europe, and other research topics related to exploration, settlement, and architecture.

The Shenvalee Golf Resort, an approximately 145-acre property located in the Town of New Market in Shenandoah County, is comprised of a golf course, lodge, motel, and other buildings dating primarily from 1926 to 1972. Originally consisting of a nine-hole golf course and the lodge, Shenvalee was largely the brainchild of businessman Roland G. Hill, who believed Shenandoah Valley residents could use a resort-type destination for recreation. After purchasing a tract near New Market in 1926, Hill set out to establish his new venture by transferring the land to Shenandoah Valley Estates, Inc., which was then named developer of the new project. As the president of Shenandoah Valley Estates, Hill hired a team of designers, engineers, and architects to oversee the resort’s construction. The golf course, which was expanded in the late 20th century and now has 27 holes, features the standard elements of tees, fairways, greens, roughs, and hazards. The Massanutten Mountain rises more than 2,900 feet to the east, while U.S. Highway 11 bounds a part of the area on the west. The resort is surrounded by residences to the south. The Shenvalee lodge, built in the Colonial Revival style in ca. 1926-27, is a two-story, brick-veneered building boasting a monumental Doric portico with a porte-cochère, a metal-sheathed side-gable roof with an attic, and rear additions. The Colonial Revival poolside motel, which dates to ca. 1959-60, stands next to the lodge and features interconnected one-story, brick-veneered wings that encircle the swimming pool. Another motel, located near the golf course, was built in 1968-69 in the Modernist style and expanded in 1972. As the resort approaches its 100th birthday, it continues to offer recreational services to visitors in the Shenandoah Valley and beyond.

The Shenvalee Golf Resort, an approximately 145-acre property located in the Town of New Market in Shenandoah County, is comprised of a golf course, lodge, motel, and other buildings dating primarily from 1926 to 1972. Originally consisting of a nine-hole golf course and the lodge, Shenvalee was largely the brainchild of businessman Roland G. Hill, who believed Shenandoah Valley residents could use a resort-type destination for recreation. After purchasing a tract near New Market in 1926, Hill set out to establish his new venture by transferring the land to Shenandoah Valley Estates, Inc., which was then named developer of the new project. As the president of Shenandoah Valley Estates, Hill hired a team of designers, engineers, and architects to oversee the resort’s construction. The golf course, which was expanded in the late 20th century and now has 27 holes, features the standard elements of tees, fairways, greens, roughs, and hazards. The Massanutten Mountain rises more than 2,900 feet to the east, while U.S. Highway 11 bounds a part of the area on the west. The resort is surrounded by residences to the south. The Shenvalee lodge, built in the Colonial Revival style in ca. 1926-27, is a two-story, brick-veneered building boasting a monumental Doric portico with a porte-cochère, a metal-sheathed side-gable roof with an attic, and rear additions. The Colonial Revival poolside motel, which dates to ca. 1959-60, stands next to the lodge and features interconnected one-story, brick-veneered wings that encircle the swimming pool. Another motel, located near the golf course, was built in 1968-69 in the Modernist style and expanded in 1972. As the resort approaches its 100th birthday, it continues to offer recreational services to visitors in the Shenandoah Valley and beyond.

In northwest Russell County, the Dante Downtown Historic District is a rare surviving example of a company coal town in Virginia that sprang into existence during the early 20th century. Spanning approximately 3.5 acres, the town was originally a small village known as Turkey Foot that developed into Dante, first by the Dawson Coal Company in 1903. Then in 1906, Dante officially became a company coal town when Clinchfield Coal Corporation acquired the town and fully developed it. By 1950, the downtown area comprised a company store, hotel, jail, post office, commercial building housing a pharmacy, and more. The surviving buildings in the district include a bank, dry-cleaning building, railroad depot, commercial buildings, and a steam-heat plant. These buildings represent the operations of the Clinchfield Coal Corporation as well as the services it provided for its workers and their families. The architectural designs within the district include Richardsonian Romanesque, Classical Revival, Main Street Commercial, and International styles. These stylistic influences reflect the periods in which they were built and the craftsmanship and materials of the region. Although their functions, styles, and materials vary, all buildings are of masonry construction and modest in scale and detailing.

In northwest Russell County, the Dante Downtown Historic District is a rare surviving example of a company coal town in Virginia that sprang into existence during the early 20th century. Spanning approximately 3.5 acres, the town was originally a small village known as Turkey Foot that developed into Dante, first by the Dawson Coal Company in 1903. Then in 1906, Dante officially became a company coal town when Clinchfield Coal Corporation acquired the town and fully developed it. By 1950, the downtown area comprised a company store, hotel, jail, post office, commercial building housing a pharmacy, and more. The surviving buildings in the district include a bank, dry-cleaning building, railroad depot, commercial buildings, and a steam-heat plant. These buildings represent the operations of the Clinchfield Coal Corporation as well as the services it provided for its workers and their families. The architectural designs within the district include Richardsonian Romanesque, Classical Revival, Main Street Commercial, and International styles. These stylistic influences reflect the periods in which they were built and the craftsmanship and materials of the region. Although their functions, styles, and materials vary, all buildings are of masonry construction and modest in scale and detailing.

The new VLR listings also highlight the history of medicine and healthcare development in Virginia during the 19th and 20th centuries:

The De Paul Hospital Complex Historic District (De Paul) in the City of Norfolk is a large evolved hospital representative of multiple generations of innovative healthcare developments and service to the Norfolk community. Located in a suburban environment between the Riverpoint and Talbot Park neighborhoods and spanning over 13 acres, the complex consists of five associated resources including the main hospital building, which first opened in 1944 as one of only two major hospitals serving the greater Norfolk area. The buildings in the complex feature a mix of Modern and International architectural elements, incorporating smooth textures, flat roofs, minimal ornamentation, and window treatments characteristic of the styles. Each building utilizes expansive amounts of brick with contrasting concrete and cast stone elements to subtly separate their features and break up the façades. As an ensemble, they boast a cohesive design representative of mid-20th century Modern and International styles.The Catholic Daughters of Charity started the hospital in downtown Norfolk in the donated home of Ann Plume Behan Herron. By 1856, it was called The Hospital of St. Vincent De Paul and served as Norfolk’s first hospital for the public. The hospital was expanded several times, growing from the single building to an institution with 150 rooms and a school of nursing. At the current location, the construction of the main hospital building, which used World War II Lanham Act funds, was the largest hospital project in the southeastern region overseen by the Federal Works Agency (FWA). As a direct result of increased demand in healthcare services following a post-World War II population growth and the advent of new healthcare treatments, equipment, and procedures, the main hospital was upgraded with several additions to accommodate those advancements during the years after its initial construction. The expansion of the main hospital and the addition of associated facilities in the medical complex reflect the innovative local and regional changes in health care. As one of two main hospitals serving Norfolk, De Paul has played a significant role as a unifying force for the city for more than 70 years.

The De Paul Hospital Complex Historic District (De Paul) in the City of Norfolk is a large evolved hospital representative of multiple generations of innovative healthcare developments and service to the Norfolk community. Located in a suburban environment between the Riverpoint and Talbot Park neighborhoods and spanning over 13 acres, the complex consists of five associated resources including the main hospital building, which first opened in 1944 as one of only two major hospitals serving the greater Norfolk area. The buildings in the complex feature a mix of Modern and International architectural elements, incorporating smooth textures, flat roofs, minimal ornamentation, and window treatments characteristic of the styles. Each building utilizes expansive amounts of brick with contrasting concrete and cast stone elements to subtly separate their features and break up the façades. As an ensemble, they boast a cohesive design representative of mid-20th century Modern and International styles.The Catholic Daughters of Charity started the hospital in downtown Norfolk in the donated home of Ann Plume Behan Herron. By 1856, it was called The Hospital of St. Vincent De Paul and served as Norfolk’s first hospital for the public. The hospital was expanded several times, growing from the single building to an institution with 150 rooms and a school of nursing. At the current location, the construction of the main hospital building, which used World War II Lanham Act funds, was the largest hospital project in the southeastern region overseen by the Federal Works Agency (FWA). As a direct result of increased demand in healthcare services following a post-World War II population growth and the advent of new healthcare treatments, equipment, and procedures, the main hospital was upgraded with several additions to accommodate those advancements during the years after its initial construction. The expansion of the main hospital and the addition of associated facilities in the medical complex reflect the innovative local and regional changes in health care. As one of two main hospitals serving Norfolk, De Paul has played a significant role as a unifying force for the city for more than 70 years. In Smyth County, the Southwestern State Hospital Tubercular Building stands on the campus of what is now known as the Southwestern Virginia Mental Health Institute. The hospital opened in 1887 as one of Virginia’s four historic-period mental healthcare hospitals. The classically inspired brick and stone building was designed in the mid-1930s by the Roanoke-based architectural firm Eubank and Caldwell. Built as two wings connected by a kitchen, the building exterior features quarry-faced limestone foundations, round-arched and square-headed windows and entries, and parapet gables with lunettes. Each wing centers on a sun porch where tuberculosis patients recuperated. The east wing also has glass-fronted bedrooms opening onto the sun porch. The interior features include an axial corridor which links together the three parts of the building: the east wing, the west wing, and a connecting kitchen. The Tubercular Building’s site, located somewhat removed from the hospital’s core, reflects its use for the treatment of an infectious disease and the need to isolate its occupants from the general hospital population. The facility historically served as an important component of Southwestern State Hospital, the principal healthcare facility serving Southwest Virginia’s white population (the first African American patient was admitted in 1967). Use of the building for tuberculosis care was discontinued in 1969. The building is currently being considered as a new home for the Appalachian Center for Hope, a residential drug treatment center.

In Smyth County, the Southwestern State Hospital Tubercular Building stands on the campus of what is now known as the Southwestern Virginia Mental Health Institute. The hospital opened in 1887 as one of Virginia’s four historic-period mental healthcare hospitals. The classically inspired brick and stone building was designed in the mid-1930s by the Roanoke-based architectural firm Eubank and Caldwell. Built as two wings connected by a kitchen, the building exterior features quarry-faced limestone foundations, round-arched and square-headed windows and entries, and parapet gables with lunettes. Each wing centers on a sun porch where tuberculosis patients recuperated. The east wing also has glass-fronted bedrooms opening onto the sun porch. The interior features include an axial corridor which links together the three parts of the building: the east wing, the west wing, and a connecting kitchen. The Tubercular Building’s site, located somewhat removed from the hospital’s core, reflects its use for the treatment of an infectious disease and the need to isolate its occupants from the general hospital population. The facility historically served as an important component of Southwestern State Hospital, the principal healthcare facility serving Southwest Virginia’s white population (the first African American patient was admitted in 1967). Use of the building for tuberculosis care was discontinued in 1969. The building is currently being considered as a new home for the Appalachian Center for Hope, a residential drug treatment center.

High-style architecture grounds three new VLR listings:

In Augusta County, Black Oak Spring is a two-story brick house dating to ca. 1820. Black Oak Spring’s distinctive brickwork and architectural elements embody the characteristics of the Colonial-, Georgian Early Republic-, and Victorian-era styles. The house has a symmetrical three-bay front, a metal-sheathed side-gable roof, a stone foundation, wood-sash windows, and gable-end brick chimneys. The front entry, with its fanlight and richly ornamented surround, is sheltered by a small Victorian-style porch. Black Oak Spring is a significant example of two architectural themes: the blending of stylistic influences in the domestic architecture of Augusta County and the region during the early 19th century, and the influence of technomorphism in architectural expression. Stylistically, the house’s interior blends the Georgian and Federal styles with technomorphic detail, an approach in which the design expresses the technology used to create it. Technomorphism is usually associated with the latter part of the 19th century, when machine production imparted a specific look to architectural elements.

In Augusta County, Black Oak Spring is a two-story brick house dating to ca. 1820. Black Oak Spring’s distinctive brickwork and architectural elements embody the characteristics of the Colonial-, Georgian Early Republic-, and Victorian-era styles. The house has a symmetrical three-bay front, a metal-sheathed side-gable roof, a stone foundation, wood-sash windows, and gable-end brick chimneys. The front entry, with its fanlight and richly ornamented surround, is sheltered by a small Victorian-style porch. Black Oak Spring is a significant example of two architectural themes: the blending of stylistic influences in the domestic architecture of Augusta County and the region during the early 19th century, and the influence of technomorphism in architectural expression. Stylistically, the house’s interior blends the Georgian and Federal styles with technomorphic detail, an approach in which the design expresses the technology used to create it. Technomorphism is usually associated with the latter part of the 19th century, when machine production imparted a specific look to architectural elements. Dameron Cottage in the Town of Amherst is a rare example of a Rustic Revival-style dwelling located about one mile south of the downtown courthouse. The cottage was constructed around 1890 by Archey and William Cullen Bibby, two African American siblings, though it remains unknown what they used it for. The Bibby brothers built the cottage as a single-pen log building with a stone fireplace. Archey died before 1912, and his heirs, along with William, sold the property to George L. Dameron, who added a second pen to the southern end of the original cabin. After George died in 1923, his brother Joyner T. Dameron, Sr., purchased the cottage in 1928 and lived there with his wife Lois. Joyner remodeled and enlarged the log cabin in the Rustic Revival style, a design influenced by the Adirondack movement in New York and popular in the western United States and the national parks during the late 19th century. The cottage’s rustic style includes exposed log walls on the interior and exterior. The interior also features batten doors and rustic hardware, simple square newel posts and balusters of the stair rail, and a simple door and window trim. Much of the house retains original wood flooring. The surrounding landscape includes a nearby creek and the yard features mature hardwoods and pines. Notably, a magnolia tree—cultivated from a seed by Lois Dameron—is located at the northwest corner of the house.

Dameron Cottage in the Town of Amherst is a rare example of a Rustic Revival-style dwelling located about one mile south of the downtown courthouse. The cottage was constructed around 1890 by Archey and William Cullen Bibby, two African American siblings, though it remains unknown what they used it for. The Bibby brothers built the cottage as a single-pen log building with a stone fireplace. Archey died before 1912, and his heirs, along with William, sold the property to George L. Dameron, who added a second pen to the southern end of the original cabin. After George died in 1923, his brother Joyner T. Dameron, Sr., purchased the cottage in 1928 and lived there with his wife Lois. Joyner remodeled and enlarged the log cabin in the Rustic Revival style, a design influenced by the Adirondack movement in New York and popular in the western United States and the national parks during the late 19th century. The cottage’s rustic style includes exposed log walls on the interior and exterior. The interior also features batten doors and rustic hardware, simple square newel posts and balusters of the stair rail, and a simple door and window trim. Much of the house retains original wood flooring. The surrounding landscape includes a nearby creek and the yard features mature hardwoods and pines. Notably, a magnolia tree—cultivated from a seed by Lois Dameron—is located at the northwest corner of the house. Located in southwestern King William County, Cherry Grove sits on a 1.25-acre parcel in the rural community of Aylett, off Manfield Road and close to the border of Hanover County. The frame dwelling, which was constructed in two stages, stands on a cleared section of land surrounded by woods on all sides. The building is situated atop a Flemish-bond basement and flanked on both sides by Flemish-bond exterior-end chimneys. The original house—a two-bay, single-pile, one-and-a-half-story dwelling—was built in ca. 1792 by its owner William Cocke (1759–ca. 1802), who purchased the property from Ralph Wormeley, the heir of an aristocratic colonial family. In 1821, the house passed to Cocke’s son Isaac, who constructed a two-story, two-bay, single-pile frame addition onto the western end of the building in ca. 1834-1835. Isaac also hired Boston-born painter Daniel T. Rea to execute interior decorative touches on the first-floor parlor mantel and baseboards, stairs, and doors. Rea, who came from a long line of Massachusetts decorative painters, designed the first-floor mantel and baseboards of the frame addition to resemble marble, and tinted the home’s door panels to look like burled walnut, maple, and mahogany. Cherry Grove is presently the only known example of Rea’s decorative work in Virginia. After Isaac Cocke died in 1835, the estate was divided among his widow, Harriet Timberlake Cocke, and their children. One of Isaac and Harriet’s daughters, Julia F. Cocke, who married Dr. William T. Downer, eventually inherited the house and tract. Descendants of the Downer family owned Cherry Grove until 1982, when it was sold to brothers James Wilson and Timothy Lee Ramsey. The current owners, Lee and Elaine Ramsey, became the sole owners in 1991 and restored the house.

Located in southwestern King William County, Cherry Grove sits on a 1.25-acre parcel in the rural community of Aylett, off Manfield Road and close to the border of Hanover County. The frame dwelling, which was constructed in two stages, stands on a cleared section of land surrounded by woods on all sides. The building is situated atop a Flemish-bond basement and flanked on both sides by Flemish-bond exterior-end chimneys. The original house—a two-bay, single-pile, one-and-a-half-story dwelling—was built in ca. 1792 by its owner William Cocke (1759–ca. 1802), who purchased the property from Ralph Wormeley, the heir of an aristocratic colonial family. In 1821, the house passed to Cocke’s son Isaac, who constructed a two-story, two-bay, single-pile frame addition onto the western end of the building in ca. 1834-1835. Isaac also hired Boston-born painter Daniel T. Rea to execute interior decorative touches on the first-floor parlor mantel and baseboards, stairs, and doors. Rea, who came from a long line of Massachusetts decorative painters, designed the first-floor mantel and baseboards of the frame addition to resemble marble, and tinted the home’s door panels to look like burled walnut, maple, and mahogany. Cherry Grove is presently the only known example of Rea’s decorative work in Virginia. After Isaac Cocke died in 1835, the estate was divided among his widow, Harriet Timberlake Cocke, and their children. One of Isaac and Harriet’s daughters, Julia F. Cocke, who married Dr. William T. Downer, eventually inherited the house and tract. Descendants of the Downer family owned Cherry Grove until 1982, when it was sold to brothers James Wilson and Timothy Lee Ramsey. The current owners, Lee and Elaine Ramsey, became the sole owners in 1991 and restored the house.

The Board of Historic Resources approved two other VLR listings, a boundary increase for a previously listed historic district and an apartment building for senior citizens, both located in the City of Richmond, in its June quarterly meeting:

The Hermitage Road Warehouse Historic District is associated with Richmond’s industrial growth and history from the early to mid-20th century. The district was originally listed in the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places in 2014 with a period of historical significance of 1913 to 1958. Located in the northwestern part of the city, just east of the neighborhood known as Scott’s Addition, the 2023 Boundary Increase and Update consists of two discontiguous areas adjacent to the original district and extends the period of significance to 1906 through 1965. After the Seaboard Air Line (SAL) Railroad connected to the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac (RF&P) Railroad in 1900, various large industrial and commercial companies established themselves within the vicinity of Hermitage Road near its intersection with the SAL Railroad. The new rail connection made the transportation of materials and products faster and more efficient than ever before. The Richmond Foundry and Manufacturing Company, which constructed its distinctive complex at 2300 Hermitage Road in 1906, was among the first organizations to take advantage of the opportunities that the railroad offered. The district, which became comprised of a cohesive group of warehouse buildings exhibiting unadorned architecture and engineering trends of the period, would subsequently go on to house several of the city’s most prominent businesses, including Richmond Foundry and Manufacturing Company, Richmond Food Stores, Inc., and Brown Distributing Co., in the current expansion. The 2014 listed area includes buildings constructed for Export Leaf Tobacco, Miller & Rhoads, and the A. H. Robins Company. The International-style Salvation Army Building, designed by leading Richmond architect Carl M. Lindner, was constructed in 1965.

The Hermitage Road Warehouse Historic District is associated with Richmond’s industrial growth and history from the early to mid-20th century. The district was originally listed in the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places in 2014 with a period of historical significance of 1913 to 1958. Located in the northwestern part of the city, just east of the neighborhood known as Scott’s Addition, the 2023 Boundary Increase and Update consists of two discontiguous areas adjacent to the original district and extends the period of significance to 1906 through 1965. After the Seaboard Air Line (SAL) Railroad connected to the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac (RF&P) Railroad in 1900, various large industrial and commercial companies established themselves within the vicinity of Hermitage Road near its intersection with the SAL Railroad. The new rail connection made the transportation of materials and products faster and more efficient than ever before. The Richmond Foundry and Manufacturing Company, which constructed its distinctive complex at 2300 Hermitage Road in 1906, was among the first organizations to take advantage of the opportunities that the railroad offered. The district, which became comprised of a cohesive group of warehouse buildings exhibiting unadorned architecture and engineering trends of the period, would subsequently go on to house several of the city’s most prominent businesses, including Richmond Foundry and Manufacturing Company, Richmond Food Stores, Inc., and Brown Distributing Co., in the current expansion. The 2014 listed area includes buildings constructed for Export Leaf Tobacco, Miller & Rhoads, and the A. H. Robins Company. The International-style Salvation Army Building, designed by leading Richmond architect Carl M. Lindner, was constructed in 1965. The eleven-story, 200-unit High-Rise for the Elderly, also known as the Frederic A. Fay Towers, represents the impacts of the Housing Act of 1959, which extended and amended laws related to the provision and improvement of housing and the renewal of urban communities, and later authorized direct federal loans for private nonprofits to develop rental housing for senior citizens. In line with this nationwide focus to provide low-income housing for the elderly, the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) constructed the High-Rise for the Elderly as its first high-rise, purpose-built residential tower for senior citizens in 1971. Completed in the International style, the building is located within the larger public housing complex known as Gilpin Court in the city’s Jackson Ward neighborhood. Smaller-scale, multi-family housing designed by prominent Virginia architect E. Tucker Carlton surround the building and its associated landscape, which was designed by Kenneth R. Higgins. Equipped with elevators, an emergency alert system in each unit, a ground-floor mailroom, laundry area, trash shoot on each floor, lounge, and cafeteria, the building provided residents increased accessibility, safety, and activities that improved overall quality of life. Residents were asked to form a “buddy system” so they could check in on each other periodically. The RRHA also offered additional services, such as transportation to nearby markets, and hosted group activities in the building’s common areas.

The eleven-story, 200-unit High-Rise for the Elderly, also known as the Frederic A. Fay Towers, represents the impacts of the Housing Act of 1959, which extended and amended laws related to the provision and improvement of housing and the renewal of urban communities, and later authorized direct federal loans for private nonprofits to develop rental housing for senior citizens. In line with this nationwide focus to provide low-income housing for the elderly, the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) constructed the High-Rise for the Elderly as its first high-rise, purpose-built residential tower for senior citizens in 1971. Completed in the International style, the building is located within the larger public housing complex known as Gilpin Court in the city’s Jackson Ward neighborhood. Smaller-scale, multi-family housing designed by prominent Virginia architect E. Tucker Carlton surround the building and its associated landscape, which was designed by Kenneth R. Higgins. Equipped with elevators, an emergency alert system in each unit, a ground-floor mailroom, laundry area, trash shoot on each floor, lounge, and cafeteria, the building provided residents increased accessibility, safety, and activities that improved overall quality of life. Residents were asked to form a “buddy system” so they could check in on each other periodically. The RRHA also offered additional services, such as transportation to nearby markets, and hosted group activities in the building’s common areas.

DHR will forward the documentation for these newly listed VLR sites to the National Park Service for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). Listing a property in the state or national registers is honorary and sets no restrictions on what owners may do with their property. The designation is foremost an invitation to learn about and experience authentic and significant places in Virginia’s history. Designating a property to the state or national registers—either individually or as a contributing building in a historic district—provides an owner the opportunity to pursue historic rehabilitation tax credit improvements to the building. Tax credit projects must comply with the Secretary of Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation.