State Adds 10 Historic Sites to the Virginia Landmarks Register

—New listings are in the counties of Accomack, Northumberland, Pulaski, Fairfax, Loudoun, Westmoreland, Halifax, and Floyd; and in the cities of Norfolk and Newport News—

Among ten places recently added to the Virginia Landmarks Register (VLR) are properties that house one of the longest-lasting blacksmith services in the Eastern Shore, a 19th-century plantation with roots dating to the state’s colonial period, a storied dwelling that once served as a rest stop for travelers along the historic Georgetown Pike, and the first school in Pulaski County to integrate following the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) establishing that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

The commonwealth’s Board of Historic Resources approved the VLR listings during its quarterly public meeting March 16, 2023. The VLR is the commonwealth’s official list of places of historic, architectural, archaeological, and cultural significance.

The Samuel D. Outlaw Blacksmith Shop is a one-story, vernacular-style building located on a 0.10-acre suburban lot in Accomack County. The shop has an open, one-room plan, with unfinished walls exposing the building’s wood framing. A reconstructed brick forge with a chimney is located along the western wall to provide space for heating metals.

According to local residents, Samuel D. Outlaw, an African American blacksmith from Windsor, North Carolina, constructed the shop where he began his business about one year after moving to the Town of Onancock in 1926. Outlaw, a 1925 graduate of the blacksmithing program at the Armstrong-Slater Memorial Trade School of Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University), worked at his shop for more than 60 years during Virginia’s segregation period providing services to Black and white watermen, farmers, carpenters, and community members throughout the Eastern Shore. Outlaw produced specialized metal tools for his clients using a forge, cast iron vessels, vises, and planers. He made repairments and also created wheels, axles, plows, and other forms of farming equipment. Locals who remember Outlaw in the later years of his business, including Virginia’s former governor Ralph Northam, recall that his shop was “the place to go” when something was in need of repair, and describe him as a “gracious and welcoming man” who treated everyone equally, regardless of race. Today, the shop serves as a museum preserving the legacy of Outlaw’s contributions to the Eastern Shore’s communities.

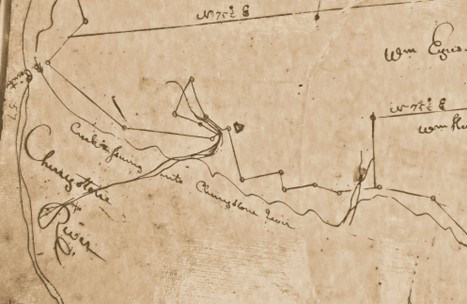

In rural Northumberland County, the magnificent 221-acre estate of Gascony encompasses a Greek Revival-style main house built in ca. 1856, a guest house, and numerous agricultural outbuildings and structures that contribute to the property’s historical milieu. The property, which is roughly bounded by Mill Creek, Gascony Cove, and Guarding Point Creek, was first settled in the mid-17th century by the Gaskins family. Members of the Gaskins family held prominent roles in the Northumberland County community. Most notably, Thomas Gaskins V, who inherited at least a portion of the estate after his father’s death in 1737, served the county in various capacities, including as a local sheriff and a delegate to the House of Burgesses from 1765 to 1768. During the Revolutionary War (1775-1783), Gaskins recruited men in Northumberland for the militia. In one of his letters to Thomas Jefferson, Gaskins recounted the sacking of his estate by British privateers in 1781. A deed from Gaskins to his son implies that the main house, which had presumably been destroyed by the British, was rebuilt by 1784. The Gaskins family continued to own the property until the 1840s, when John Hopkins Harding, Sr., purchased the lands from William M. and Susan Gaskins and Hannah H. Ball. Oral tradition passed down by the Harding family contends that the current ca. 1856 main house was built on the foundations of Thomas Gaskins V’s original dwelling. Although current research has not confirmed this oral tradition, future archaeological and documentary investigations may reveal information relating to the original Gascony dwelling’s location and about the lives of the enslaved African Americans who lived and worked on the property.

In Fairfax County, Drover’s Rest is a one-and-a-half story dwelling located along the north side of the Georgetown Pike in McLean. The building was constructed ca. 1757 to 1785 by prominent landowner Bryan Fairfax in support of an 18th-century mill complex on Difficult Run. Situated southwest of the Potomac River, the present property on which the dwelling stands once formed a portion of Fairfax’s larger estate, Towlston Manor. The setting of the dwelling’s location retains its rural, wooded character, with heavy tree growth screening the house from the historic Madeira School in the east.

Drover’s Rest is representative of the history of early milling and road development during the mid- to late 18th century. The house continued to be associated with the mill complex into the 1840s, but after 1866 it was documented by one of its previous owners as an inn for travelers along the Pike, which was constructed between 1813 and 1827 as a roadway linking merchants in Georgetown with the farms and plantations of northern Virginia. As a “drover’s rest,” the house provided lodging for livestock drovers, teamsters, and stagecoach travelers on the turnpike into the early 20th century. In 1975, renowned biologist and environmental conservationist Dr. Thomas E. Lovejoy purchased Drover’s Rest, where he would live, entertain, and complete some of the most important work in his distinguished career until his death in 2021.

In Pulaski County, Pulaski High School stands within a small residential area off U.S. Route 11, just northeast of downtown. This two-story Georgian Revival building was originally constructed in 1937 as a smaller elementary school known as the Pico Terrace School. Several additions were added to the main building during the 1950s to support its conversion to a high school and to accommodate an expanded student population. Pulaski High School was the first school in the county to racially desegregate, beginning with 14 Black students gaining access through the federal court system in the fall of 1960. Before the Civil Rights era, African American students in Pulaski County did not have access to a high school. Those who wanted to attend high school were bussed to the Christiansburg Institute in neighboring Montgomery County. It would not be until 1966 that Pulaski County Schools were fully integrated. After being replaced by a new consolidated county high school in 1974, Pulaski High School was converted to a middle school and remained open until 2020.

The new VLR listings also highlight the impact of commerce on the commonwealth’s historic districts and towns:

- The Montross Historic District comprises approximately 170 acres and encompasses a significant concentration of historic architectural resources along Virginia State Route 3/Kings Highway in the Town of Montross, established as the Westmoreland County seat of government in the 1680s. The heart of the district consists of the early 20th-century courthouse and court green, which stand on the site of the former colonial-era courthouse erected in ca. 1685. The district, which extends in a linear fashion along Virginia State Route 3/Kings Highway, is situated within the largely rural and agricultural landscape of Westmoreland County. The district’s historic architectural resources, including governmental and commercial buildings, residences, schools, and churches, mostly date to the early 20th century. The courthouse was first built in 1900 and remodeled in 1936, while the former jail was constructed in 1911. The Inn at Montross/Spence’s Tavern, which dates to the 19th century, is the oldest resource in the district. Important landscape elements include the former courthouse square, which is the site of several military memorial markers, and the “Virginia Presidents’ Garden” designed in ca. 1940 by noted landscape architect Charles Freeman Gillette of Richmond. The district’s buildings reflect assorted architectural styles, including Colonial Revival, Classical Revival, Vernacular, and commercial designs. The Federal, Gothic Revival, and mid-century Art Deco styles are also represented. Together, these historic resources represent the development of the Town of Montross from a small, but vibrant, court house village to an important commercial and transportation hub on Virginia’s Northern Neck.

- Nestled in western Loudoun County, the Philomont Historic District is a rural village located at the crossroad intersection of Snickersville Turnpike and JEB Stuart Road, atop a slight rise above Butcher’s Branch to the west. Residences in the village are organized so that many face one of these two roads. The general store, community center, and fire station anchor the village, which spans approximately 43 acres and includes vernacular-style buildings – generally local interpretations of nationally popular revival styles – made of native materials, such as log and stone. Many Philomont houses, the earliest of which were built in the late 18th century, include full or remnants of porches, an architectural feature that was once common in the village and likely the hallmark of local carpenters and woodworkers. Philomont and its sister communities, Airmont and Mountville, share settlement patterns derived from the growth and decline of commerce along the Snickersville Turnpike. Historically, all three villages drew economic vitality from developments along the Turnpike. The completion of the Turnpike and Hibbs Bridge fueled Philomont’s building boom of the 1830s and 1840s. While early dwellings also functioned as retail outlets, services, or workshops, purpose-made commercial establishments became more common in the village in the 1840s and 1850s. Philomont’s second building boom occurred during the decades of 1870 and 1880, coinciding with repairs made to the Turnpike after the end of the Civil War. Despite a few modern intrusions, Philomont continues to retain much of its pristine and rural setting today.

The effects of the urban renewal movement in the United States during the 20th century grounds two new VLR listings:

- In the 1950s, the City of Norfolk and the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority (NRHA) carried out a series of urban renewal and redevelopment programs to reshape downtown. These programs, alongside significant legislative action in Virginia to change the structure of the financial industry statewide, resulted in the development of the Downtown Norfolk Financial Historic District. A 19-acre commercial sector located in the heart of downtown, the district consists of a collection of high-rise buildings, parking decks, plazas, and pedestrian walkways designed in International, Brutalist, New Formalism, and other modernist styles by nationally and locally renowned architecture firms. The development of the district began in 1967 with the construction of the Virginia National Bank Headquarters Building. Starting from the 1950s, when planning efforts began, into the ‘60s and ‘70s, the city and the NRHA prioritized designs and improvements to the district’s infrastructure to ensure convenience for travelers on automobiles and pedestrians, a decision the city hoped would, in turn, keep people and businesses downtown. Constructed as part of the Downtown Norfolk revitalization plan, the buildings and structures of the financial historic district are a testament to the city’s efforts to be seen as a successful and modern financial center comparable to that in the commonwealth’s capital city of Richmond.

- Located within the southern end of the City of Newport News, the Newport News Downtown Historic District exemplifies nearly 100 years of historical change and growth during the urban renewal movement, which reached its peak in the country in the mid-20th century. Evolution of this 91-acre district began in the late 19th century and continued for the next 60-plus years as the city attempted to reverse the impacts of rapid suburbanization, aiming to retain residents and businesses downtown through redevelopment and federal programs. The district encompasses a wide variety of architectural designs, from the International, Brutalist, and New Formalism styles to more traditional types, such as the Romanesque and Gothic and Colonial Revival buildings in the northern parts of the district. Parking lots and garages interspersed throughout the area indicate the city’s efforts to support citizens’ increasing reliance on the automobile during the 20th century. Common exterior materials found on buildings include brick veneer, stone, concrete, and vinyl siding. Many churches boast additions to accommodate growing congregations and expanded community services. The height of the district’s redevelopment era ended in 1973, just shortly before the creation of Interstate 664.

The Board of Historic Resources approved two other VLR listings, a boundary increase for a previously listed historic district, as well as a multiple property document (MPD), which facilitates designation of properties with similar historic background and character to the registers, in its March quarterly meeting:

- The Roberson Mill, located on the West Fork of Dodd Creek in south central Floyd County, was built by miller and blacksmith John W. Epperly in the mid-1880s and acquired by miller Homer Roberson in 1931. It was one of the last two commercial mills to operate under water power in the county and one of only two existing flour mills that was neither designed to incorporate a roller mill nor modified afterward to accommodate one. The Roberson Mill represents, therefore, the county’s most authentic picture of flour milling as it was done in the United States through most of the 19th century. The frame building is two stories, with the waterwheel location on the east side. Two sets of millstones with a chamfered wooden hoist, and a buckwheat huller are safely intact within the mill, along with well-preserved machinery including two rare bolting chests. Among Roberson Mill’s unusual features are a split-level main floor and the absence of a basement. The Roberson Mill was last in operation around 1988 under the ownership of Homer’s son Harry Roberson. The mill is currently being restored by the non-profit Friends of Roberson Mill.

- The imposing two-story, five-bedroom Greek Revival mansion of the Clarkton estate stands atop a promontory near the Staunton River in rural Halifax County. Built for Charles Clark between 1844 and 1848, the house’s brick exterior is rough-coated and scored to simulate granite or marble blocks, and features a monumental two-story Doric portico with paired columns. The house represents one of the finest examples of the Greek Revival style of architecture in Halifax County. Originally known as Rosebank, and later as Hoveloak (an Indian name for “high promontory”), the estate was renamed to Clarkton around the turn of the 20th century by Charles Clark's son, Thomas. At its peak, Clarkton included over 6,000 acres. Directly in front of the house is an alley of large English boxwoods extending from the portico to an iron-gated entrance. The grounds include additional rows of Osage Orange trees, American Holly trees, and oak trees, as well as a grouping of mid-19th century dependencies behind and flanking the main house, which are significant for both their age, historic functions, and architectural interest.

- Previously listed on the historic registers, the Lower Basin Historic District defines the City of Lynchburg’s historic wholesale and industrial center. The district’s 2023 Boundary Increase is located on a low terrace that extends between the south bank of the James River and a parallel ridge, and it stretches to a length of Main Street south and east of the current historic district. The history of the Boundary Increase area is tied to the historic development of the original historic district and Lynchburg as a whole. The Lynchburg riverfront had historically been industrially focused, with businesses using first the river and then the James River-Kanawha Canal to ship materials and products east. However, the coming of the railroad in the mid-19th century allowed for larger businesses and companies such as Helme Tobacco, a national company, to set up shop in the city. The new boundaries of the Lower Basin Historic District incorporate historic industrial and commercial buildings that contributed to the success and growth of the city.

- African American Watermen of the Virginia Chesapeake Bay MPD was created as part of a three-state effort involving Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, to recognize the contributions of African American watermen to the seafood industries of Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay. The MPD provides the historic context for African American watermen within a portion of Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay watershed, which is defined as the tidal waters east of the fall line that drain into the Chesapeake Bay. While the MPD focuses on a select number of counties within the study area, the historic context is inextricably linked to all of those geographic areas within this portion of the watershed. The MPD concentrates on the resources associated with African American watermen during and after the Reconstruction period. However, to document and recognize all possible associations with African American watermen, the historic context provided in the MPD begins with an overview of the origins of African American watermen in Virginia's earliest colonial contact period.

DHR will forward the documentation for these newly listed VLR sites to the National Park Service for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.

Listing a property in the state or national registers is honorary and sets no restrictions on what property owners may do with their property. The designation is foremost an invitation to learn about and experience authentic and significant places in Virginia’s history.

Designating a property to the state or national registers—either individually or as a contributing building in a historic district—provides an owner the opportunity to pursue historic rehabilitation tax credit improvements to the building. Tax credit projects must comply with the Secretary of Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation.