Remembering What We'd Rather Forget–Memento Mori

The image of the naked skull and crossed femurs is a universal symbol that warns viewers of the presence of mortal danger. From poison to pirates, that hard grin is a reminder of the basic fragility of the human body. The same imagery can be seen in artwork, including funerary art, with human skulls and bones used in both portraiture and still life painting to reference the brevity of life. This artistic tradition is known as memento mori, Latin for “remember death.”

In Europe the tradition has deep roots in the 13th to 18th centuries, and likely reflects the grim acknowledgment of the realities of death brought about by successive waves of famine, war, and plague. The Western philosophical underpinnings of this attitude are many, beginning with Socrates, who posited that fear of death was pointless as no human being knew what, if anything, lay on the other side of that veil. In the context of funerary art, memento mori serves as a visual confirmation that—all philosophies and spirituality aside—the physical reality of death is the same for everyone.

The use of memento mori in the United States began with Puritan immigrants, who brought both their familiarity with the frailty of human life and their aversion to unnecessary embellishment to North America. The iconic skull, with or without crossed bones, fit the Puritans’ aesthetic nicely and can be seen in 17th-century graveyards throughout New England and the upper Mid-Atlantic.

This stark, plain imagery can occasionally be seen in early 17th-century funerary markers in Virginia, although it is uncommon and appears to be confined to high-status gravesites. The capstone for Edward Travis (1700), located on Jamestown Island next to the reconstructed church, is a good example of this form. An evolution of the straightforward iconography that pairs an often-stylized skull with wings is known as a death’s head and comes into regular use in the early to mid-18th century. This form eventually transitions into the winged cherub common in the later 18th century, which itself reflects the beginnings of the larger theoretical transition from death as ending to death as doorway.

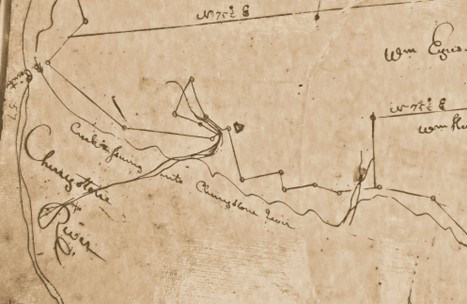

As white society moved away from its Puritan roots (and its strict biological interpretation of death), the iconography associated with memento mori changed as well. In addition to images of decay, the range of symbols grew to include the outlines of the tapered and hexagonal coffins in common use at the time, as well as images of sexton’s tools (pick and spade), themselves a reminder of the grave. A good example in Virginia may be found in Falmouth Cemetery just north of Fredericksburg, where two capstones in the form of hexagonal coffins (see photo below) are located.

The use of memento mori evolved along with the American attitude toward death, veering farther away from the blunt-force imagery of the 17th century to embrace a much more metaphorical iconography. Instead of skulls, bones, and coffins, stone carvers focused on representational imagery—urns standing in for the physical body, hourglasses to acknowledge the finite nature of life (often with added wings: essentially, “time flies”), and cut or broken flowers and branches to symbolize life cut tragically short. The focus on a gentler, indirect visual language persisted through the late 19th century, when it was generally replaced by modern styles containing little to no symbolic meaning. This likely reflects yet another change in the American way of death, away from its home-centered and deeply personal beginnings to the current sterile and often hospital-based reality of today.

Next time in GraveMatters: Trees, trees, and more trees.

–Joanna Wilson Green

Cemetery Preservationist

Community Services Division, DHR

Other readings:

2007 Greene, Meg. Rest in Peace: A History of American Cemeteries. Twenty-first Century Books: Minneapolis, MN.

2000 Ludwig, Allen. Graven Images: New England Stone Carving and its Symbols, 1650-1815. Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, CT.

1990 Williams, Richard Hayes. The Expression of Common Value Attitudes toward Suffering in the Symbolism of Medieval Art. Garland: New York, NY.

Var. Plato’s Apology of Socrates and Crito