Rediscovering the Blick Plantation Home in Southside Virginia

After a decades-long search, one family uncovers their 18th-century ancestral home along with the lessons from its history in rural Brunswick County. Read more about the Blick family's search and take a virtual tour through photographs of the plantation's main house and grounds.

By Joanna McKnight | DHR Eastern Region Preservation Specialist

In 1952, 5-year-old Earl Blick accompanied his father on a visit to the site of his ancestral home—historically known as the Blick Plantation or Holly Grove—in Brunswick County, where they attempted to find the family cemetery on the property. At the time, Earl could not have guessed that his search would continue for the next 71 years, culminating in the rediscovery of the property in 2023.

The Blick Plantation dates to the mid-18th century and was once a large tobacco plantation and millseat with approximately 1,000 acres at the peak of its production. While research is ongoing, Blick family papers, maps, photographs, and other documents provide insight into the history of the main house and land, the lives of family members, agricultural operations, and even lesser-known details of the enslaved laborers who worked and lived on the plantation. The Blick family owned the plantation until 1919, at which point the house and the contents within, the outbuildings on the grounds, and the rest of the land were catalogued and sold out of family ownership. However, Blick family burials continued in the cemetery for years thereafter. As generations passed, the family lost track of the property entirely and the land was subdivided multiple times, eventually dropping off the county property tax records.

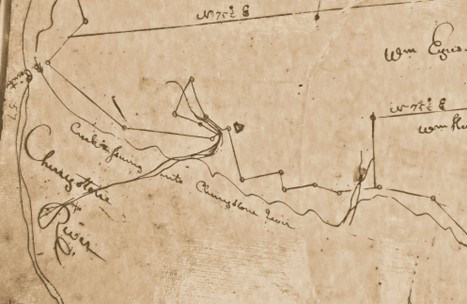

Throughout his adult life, Earl Blick continued his father’s pursuit of the historic cemetery. Its approximate location was documented in family papers and passed down through oral tradition. In the 27 years that Earl worked in the area, he drove around on his lunch breaks hoping to find the remains of the plantation’s main house and family cemetery. Blick was at a disadvantage in his search when he relied solely on an old family-drawn map and on family recollections; the map was outdated, and at the time it was drawn, the main access road did not yet exist. The old map showed the driveway to the house encompassing what is now the main access road, but the family was unaware of the connection between the two.

Earl continued the search and eventually included his son Richard in the effort. They continued the exploration started years earlier by Earl’s father. As time passed, Earl prioritized finding his grandmother’s grave site, but faced difficulty as the landscape had changed over time to include new roads, land subdivision, and the overgrowth of wooded areas. The plantation’s acreage had vastly shrunken in size. Most of the land had been subdivided into five- and ten-acre parcels in the 1980s. Before that, the plantation’s main house—the only known residential building in the vicinity—was not visible from the public road due to the wooded landscape.

Still, Earl and Richard continued their research. In 2012, they identified present-day Wilson Creek Lane as the road nearest to the cemetery. Eleven years later, in July of 2023, they planned an all-day excursion in the projected area of the historic plantation. Richard referenced maps dating to the Civil War and early 20th century and used modern mapping technology to plot a search route, but they failed to identify any sign of a cemetery or house among the wooded areas between developed parcels. Then, as they drove, they noticed a “For Sale” sign on the edge of the road. Since the sign marked the only evidence of a defined parcel within the search area, Richard took a photo of the sign and found the listing online. He magnified an aerial photograph on his computer and noticed what appeared to be a building. He immediately knew that this was the site they had been targeting for years.

After signing a safety waiver with the seller’s real estate agent, Richard made his way through the dense vegetation of the parcel and found himself staring at a two-story frame house in disrepair. The 4-feet-high side entrance door was missing its access steps, so he pulled himself up and over the threshold into a large room. Inside, Richard stood on hardwood floors, face-to-face with the room's plaster walls that feature wood trim and wainscoting. He studied its paneled doors. The house proved to be worth the years of research and exploration that his family had put in. It was highly intact and retained most of its 18th-century features and materials, with a few changes dating to the early 19th and 20th centuries. Prominent mortise-and-tenon framing stood feet away from a high-style Chinese Chippendale balustrade at the top of a winding staircase. As Richard would later discover, neither a kitchen nor interior bathrooms had ever been added in the house. Bullet-fuse electricity and a telephone line were connected to the building in the mid-20th century, but the house was only wired for pull-string ceiling lights and one two-prong wall outlet.

The Blicks negotiated with the property owner, and on November 7, 2023, they purchased the ten-acre property. The acreage primarily consists of unmanaged woodland and overgrown grounds that compromise the former driveway; remnants of structures and buildings; and clusters of periwinkles that surround many depressions and stone markers signaling unidentified burial locations.

In clearing the property by hand, Richard also discovered the long-lost family cemetery. Located directly behind the main house on a slight ridge fenced by metal stakes, the cemetery featured unmarked depressions and burials that have yet to be formally evaluated by archaeologists. The vast number of burials could correlate with the plantation’s large size and the enslaved laborers who lived and worked on the property. While research is in a preliminary stage due to the condition of the site, the Blick family hopes that the land, building, and structural remnants of the property will become resources for research and education that will result in a better understanding of the stories of those who once worked and lived on the property. After the house is stabilized, a more intensive examination of its architecture and materials will be possible. The house provides a rare opportunity to study an unrestored 18th-century dwelling in rural Brunswick County.