Grave Markers for Veterans: Military History in a Rural Cemetery

A visitor to most cemeteries in Virginia sees markers for servicemen and servicewomen who served from the Civil War up to the present. The stone slabs, made famous by images of row upon row at national cemeteries such as Arlington, are stark reminders of the sacrifices made by those who answered the call to duty. These markers are found in cemeteries large and small, in urban and rural areas, in church cemeteries established in the 19th century, municipal burying grounds of the early 20th century, and privately owned lawn cemeteries of the post-World War II period. [1]

The Oak Grove Baptist Church Cemetery in York County is a rural cemetery for a historically Black church established after the Civil War (1861-1865). The cemetery is significant for its association with Black history in York County and for the remarkable range of funerary art it contains. Distinctive characteristics include a range of government-issued military marker designs reflecting historic periods for veterans from the Civil War onward.[2]

Early Standardized Military Markers

The marker for John B. Whiting (photo), who served in the 5th Regiment Massachusetts Cavalry, commemorates service in a segregated unit assigned to Fortress Monroe, City Point (Hopewell), Petersburg, and Richmond during 1864-1865.[3] Among the marker’s notable attributes are the sunken shield and the inscription in bas-relief (raised lettering). It presents the earliest standardized design used for U.S. government-issued stone markers and is known as the “Civil War” headstone type.[4]

The name of the war associated with Whiting's service is not included, nor are Whiting’s birth and death dates. Such information was omitted on government-issued markers until the 20th century.

Veterans of the Spanish-American War received government-issued markers almost identical to those issued for the Civil War. One difference, the abbreviation “SP-AM” could be included to differentiate markers of those who had served in the much briefer Spanish-American War, fought April to December 1898, from veterans of the Civil War.

World War I Era Design

The Oak Grove Baptist Church Cemetery also has markers for veterans of World War I, which the United States entered on April 6, 1917.

After the fighting ended with an armistice on November 11 (now Veterans Day), 1918, a board of military officers composed of Assistant Secretary of War J.M. Wainwright, Army Chief of Staff General John J. Pershing, and Quartermaster General Harry L. Rogers authorized a new design, popularly known as the “General” type, for government-issued grave markers. They specified it could be used for all military graves except for those of the Civil War and Spanish-American War.

The World War I–era design is less austere than the earlier design. The inscription typically includes the name of the military member, along with their rank, regiment and division, state of origin, and date of death. For the first time, a religious emblem was added to the standardized design, but options were limited to a Latin Cross for Christian or a Star of David for Jewish faiths.[5] Interestingly, on the World War I–era marker, only the symbol of faith is in bas-relief, the lettering is recessed.

George Robinson (see photo) served under the U.S. Army’s 93rd Division in the 369th Infantry Regiment, one of just three all-Black National Guard regiments that fought in World War I. Each regiment was assigned to a French division upon reaching Europe. The 369th gained the nickname “Harlem Hellfighters” for their valor and tenacity on the battlefield: The regiment took part in major operations in the Champagne-Marne, Meuse-Argonne, Champagne and Alsace campaigns … [and] spent 191 days on the front-line trenches. For its actions, the 369th was cited 11 times for bravery and was decorated with the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Star for service during the Meuse-Argonne campaign.[6]

George Robinson’s date of death, August 1, 1917, occurred during the Second Battle of the Marne (July 15–August 6, 1918), widely considered to be the turning point of the war on the Western Front.[7]

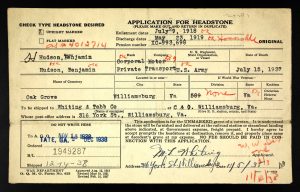

A later design example approved after World War I is the marker for Benjamin Hudson (photo), who died on July 15, 1937.

The marker’s inscription bears the same information as George Robinson’s, who died almost 20 years earlier: name of the military member, along with their rank, regiment, and division, state of origin, and date of death. The symbol of faith on Hudson’s marker is the same bas-relief design as Robinson’s marker.

In Hudson’s case, however, the sparsity of information on his marker makes it difficult to understand the time and place of his service.

During World War II, in 1944, the Under Secretary of War authorized adding the service member’s date of birth as part of a marker inscription. After the war ended, he authorized “World War I” or “World War II” be added to inscriptions as well.

Benjamin Hudson’s marker predates both of these decisions. With this information available, however, a cemetery visitor will know that Hudson served in World War I but his death (1937) occurred a few years before the U.S. entered World War II (1941).

The National Cemetery Administration of the Department of Veterans Affairs maintains the records of applications that family members or other authorized applicants of a deceased veteran could submit to obtain a government-issued veterans grave marker.[8]

The application for Hudson’s marker includes information about his service and date of death, as well as the dates of his enlistment (July 29, 1918) and honorable discharge (May 23, 1919). Information about the applicant, including shipping address, also is available, along with notes made by the government staff member who reviewed the application and the date the marker was shipped.

World War II and Post-War Designs

Albert Strong Jr.’s grave marker (photo) is an example of the post-World War II–approved design. In addition to his symbol of faith, state of origin, rank, regiment and division, his dates of birth and death are included.

After World War II, birth dates appeared on veterans’ markers, although that information was not always available due to inconsistency in creating and maintaining birth records across the country. Strong died in 1966, more than 20 years after his World War II service. His marker’s inscription notes his service in the 432nd Port Company Transportation Corps.

During the war, U.S. military forces were racially segregated as they had been throughout the nation’s history. African Americans served in all-Black units, often in support roles, but these were every bit as important to the war effort as front-line infantry, medical, communications, and other units.

The Transportation Corps was responsible for creating and maintaining a constant stream of supplies to wherever lines of engagement were established, from Europe and North Africa across Asia and down to the South Pacific. Their work included loading ships manually and with heavy equipment such as cranes. Tanks, gasoline, guns, food, and other necessities were loaded on a 24-hour basis, even when the transport units themselves were under fire. Soldiers typically were on duty for 12 to 24 hours at a time.[9]

Two other markers for World War II veterans at Oak Grove Baptist Church Cemetery are examples of slight variations on the “General” marker type that remains in use today.

The marker for Thade Hall, who served in the Army as a Private First Class during World War II shows his birth and death dates, but not the military regiment and division. Robert W. Cowles achieved the rank of Sergeant in the U.S. Army during World War II. He received an almost identical marker, although his death occurred approximately 9 years after Thade Hall’s.

Flat Markers

An example of the flat-profile markers the federal government began issuing is found at the grave of James Green, who survived the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Green served in the U.S. Army and his marker lists his rank as “Tec 5,” meaning he was a non-commissioned officer with a pay grade the same grade as corporals, but ranked one level below corporals. Technician ranks were developed to provide extra pay for soldiers who had extra skills and/or experience but who did not have a leadership role of a traditional noncommissioned officer. There was no one job description for a technician because the duties they performed depended on their military occupational classification.[10]

Flat markers gained popularity during the mid-20th century as lawn cemeteries proliferated. As the name suggests, such cemeteries feature broad expanses of grassy lawns with grave markers placed flush to the ground. To assure the marking of all graves of all eligible members of the armed forces and veterans interred in private cemeteries, who due to cemetery regulations were permitted only a flat marker type, a flat marble marker design was adopted August 11, 1936. One month later a flat granite marker type was adopted September 13, 1939. An act of April 18, 1940, authorized the use of other materials and flat bronze markers were adopted on July 12, 1940. A new design was approved beginning with federal fiscal year 1973.[11]

Korea and Vietnam

After World War II ended, the United States had to begin reconciling its goal to be a beacon of freedom to those abroad while tolerating Jim Crow segregation and racial discrimination at home. The need for change reached even President Harry Truman, who had to overcome a lifetime of his own prejudiced beliefs to commit to civil rights for everyone.[12] On July 26, 1948, President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 abolishing all racial segregation in the U.S. military and ordering full integration in the federal workforce “without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.” Considerable resistance to the order among white servicemembers hampered the pace of desegregation, but by the end of the Korean War, almost all of the military was integrated.

In February 1951, the Buddhist emblem became the third symbol of faith approved for usage on government-issued markers. By this time, the armed conflict in Korea had begun. The Secretary of Defense directed that the word “Korea” be included as part of the authorized inscription for servicemembers who served within the areas of military operations in the Korean Theater between June 27, 1950, and July 27, 1954.

A decade later, a similar authorization was provided to include the word “Vietnam” for servicemembers killed while in service, retroactive to 1954, and was later expanded to apply to all servicemembers who were “in country” (in Vietnam) between February 28, 1961, and May 7, 1975.

Rudolph Streeter’s grave marker (photo below) exemplifies the bronze, flat marker that the federal government began issuing in 1940. His marker includes his rank, Specialist 4, which signifies a noncommissioned officer rank, and denotes his service in the Vietnam War as well as his birth and death dates.

Starting with World War II, government-issued marker designs included less information about the servicemember’s military career, but birth dates (when available) and death dates were included as standard practice. This information assists descendants and genealogists with conducting further research into the individual’s life, especially as genealogical data has become increasingly available through massive projects to digitize vital records.

At Oak Grove Baptist Church Cemetery, the marker for Cornelius C. Bartlett (photo) is among the more recent government-issued markers for veterans. Bartlett apparently served during peacetime, as no war or conflict is included on the inscription. It does state that he served in the U.S. Army and provides his birth and death dates. Bartlett served after the military was racially integrated, but otherwise information about his time in the Army is not apparent on the marker.

Researchers who would like to learn more about military burials and government-issued veterans’ grave markers will find ample information at the websites operated by the National Cemetery Association (NCA) and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). The NCA’s records pertain only to those individuals who are interred in a national cemetery (including those that are overseas). NARA’s records include military servicemembers from 1862 to the present.[13] Additionally, a private genealogical website, Family Search, hosts an online, searchable database of headstone applications for U.S. Military veterans that is available with creation of a free account. Another free website that is a great place to start is History Hub, maintained by NARA staff.

–Lena S. McDonald

Historian, Register Program, DHR

Read other blogs about Virginia’s historic cemeteries

Footnotes:

[1] “History of Government Furnished Headstones and Markers,” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration, https://www.cem.va.gov/history/hmhist.asp, accessed September 13, 2021. The U.S. government has provided standardized grave markers for military veterans for more than 150 years. The first such markers were issued to mark the graves of soldiers who died while in service at frontier outposts and garrisons during the 1850s. Originally, such markers were made of wood and, therefore, subject to weathering and decay within a few years. During the Civil War, battlefield graves received similar wood markers. After the war, the U.S. government established national cemeteries and undertook a comprehensive effort to recover battlefield burials and remove fallen soldiers to the newly created cemeteries. In 1873, Secretary of War William W. Belknap adopted the first design for stones to be erected in national cemeteries. The same year, Congress granted the right to burial in national cemeteries to all honorably discharged Civil War veterans. In 1879, Congress authorized use of the stone marker for graves in private cemeteries as well. In addition to the Civil War, the stone markers were made available to mark burials for eligible deceased of the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, Mexican War, and the Indian Campaigns. By the late 19th century, deceased of the Spanish-American War were added to the list of eligible burials. Since then, graves of servicemembers who served in World War I, World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War, and in campaigns such as Panama, the Persian Gulf, Somalia, and onward to the present have been eligible for the distinctive military markers.

[2] All photographs herein were taken by DHR archaeologist Mike Clem in 2016.

[3] “Battle Unit Details: Union Massachusetts Volunteers, 5th Regiment, Massachusetts Cavalry (Colored),” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UMA0005RC00C, accessed September 13, 2021.

[4] Ibid., Jennifer M. Perunko, “The Evolution of Government Headstones and Markers,” 2009 Nationwide Cemetery Preservation Summit, https://www.ncptt.nps.gov/blog/the-evolution-of-government-headstones-and-markers/, accessed September 13, 2021. Reproductions of the Civil War marker are now available through the National Cemetery Association, https://www.cem.va.gov/hmm/pre_WWI_era.asp.

[5] “History of Government Furnished Headstones and Markers.”

[6] Army National Guard Staff Sgt. Michelle Gonzalez, “Black History Month: Highlighting the 93rd Division in World War I,” https://www.nationalguard.mil/News/Article/653966/black-history-month-highlighting-the-93rd-division-in-world-war-i/, accessed September 13, 2021.

[7] Stephen C. McGeorge and Mason W. Watson, The Marne, 15 July – 6 August 1918, The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War I Commemorative Series (Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington DC, 2018), p. 7.

[8] The National Cemetery Administration’s website address is https://www.cem.va.gov/. The website includes a nationwide “Grave Locator” database that can be searched to identify burial locations of veterans and their family members in VA National Cemeteries, state veterans cemeteries, various other military and Department of Interior cemeteries, and for veterans buried in private cemeteries when the grave is marked with a government grave marker.

[9] Douglas Bristol Jr., “What Can We Learn About World War II from Black Quartermasters?” The National World War II Museum, New Orleans, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/world-war-ii-black-quartermasters, accessed September 13, 2021.

[10] Jason Atkinson, “Seeking Explanation of Duties of Army Tech 5,” https://historyhub.history.gov/thread/7682, accessed October 4, 2021.

[11] “History of Government Furnished Headstones and Markers,” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration, https://www.cem.va.gov/history/hmhist.asp, accessed September 13, 2021.

[12] DeNeen L. Brown, “How Harry S Truman went from being a racist to desegregating the military,” The Washington Post July 26, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/07/26/how-harry-s-truman-went-from-being-a-racist-to-desegregating-the-military/, accessed September 13, 2021.

[13] Note that applications for burials of veterans of the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, Mexican War, and Indian Campaigns after Congress authorized their inclusion in the government-issued marker program in 1879.