Cornerstone Contributions: Virginia Is for Huguenot Lovers

Editor’s note: All of the previous articles in this series have been based on artifacts from the copper cornerstone box. For Valentine’s Day week, we have this special offering on a book found in the lead container under the Lee monument in Richmond. The inventory for this container can be found at the end of this article.

On a cold, bleak day in December of 2021, a crew charged with removing the Lee Monument pedestal finally found what they thought to be the long-sought-after cornerstone box. A small metal box was removed and rushed over to the conservation lab at DHR. After painstakingly long hours of gently opening the box, the contents were ultimately revealed by my former colleagues Kate Ridgway and Chelsea Blake. Soon, it was surmised that this was not THE box (news articles told of a box buried with fanfare, press coverage, etc.), but another box.

The box’s contents, wet from condensation, included: an 1875 almanac; a plumbing supply catalog; a silver 1887 British Victorian penny; an envelope with a photo of master stonemason James Netherwood, made by Virginia Artists Studio; an 1888 brochure by Collinson Pierrepont Edwards Burgwyn titled “Civil Engineer of the Natural Advantages and Water Power Facilities of the City of Manchester and the County of Chesterfield with Accompanying Maps.”

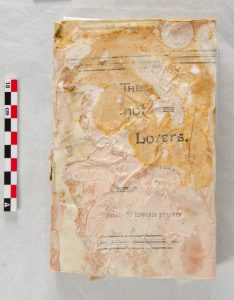

The contents of the box did, in fact, document the builders of this monument—and this particular box was a time capsule in its own right. All of the contents made sense, except for one final historic inclusion: a copy of the 1889 book, The Huguenot Lovers: A Tale of the Old Dominion, by Collinson Pierrepont Edwards Burgwyn, A.B., C.E., M. Am., Soc. C.E.

Wait, what?!?

I immediately decided I absolutely, positively, HAD to read this novel. Mr. Burgwyn was the consulting engineer for the monument, but was it possible that a civil engineer could also pen a “bodice-ripper” romance novel?

“This is good stuff,” I thought. So, I sat down with a large matcha latte in hand and read an original scan of the book available for free on Google Books—and so began my introduction to the tidy literary oeuvre of C.P.E. Burgwyn.

The story is an amorous tale of courtship between a young woman of Bostonian aristocracy and a former Confederate General. The couple not only suffer the slings and arrows of love itself, but also manage to wound each other with words. They wield their merciless tongues and sharp wits as weapons in the latest struggle of North vs. South—their courtship. Our heroine–Ms. Edyth Prescott—is brought to Richmond by her father so she may learn about his native city. This southern sojourn ends up being more than she bargained for. But no spoilers here. That said, it should be noted, that the ending of The Huguenot Lovers is both sudden and ambiguous—and open to interpretation.

The first paragraph of the Preface explains how and why the book came to be:

“In the Autumn of 1888, the Author was engaged in assisting at the transferring of the Monitor fleet from City Point to an anchorage near Richmond, Va. After the heavy vessels were under way, there was an interval of several hours each day, in which he had no duties to perform, and it was during that brief respite from the demands of a busy professional career that most of the pages were written.”

The novel is very much of its time—there are good aspects, but there are also characterizations of people that today would be deemed racist. However, if one is able to look past that, it is an interesting portrait of Richmond after the Civil War.

The Colonel takes our young heroine on carriage rides and introduces her to Libby Prison, the James River, and other sites around the former Capital of the Confederacy. I don’t know if I would choose Libby Prison as one of my destinations for an evening rendezvous, as it was a location where much human misery ensued during the Civil War—but Burgwyn clearly wanted to make a point about the South and dispel “rumors” here.

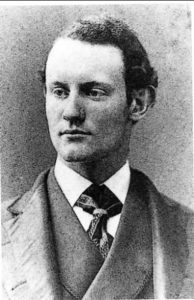

It is often said that all art is autobiography. The book was not just the dalliance of a bored southern engineer between projects. C.P.E. Burgwyn was a southerner, yes, but also a Harvard man whose mother (Anna Greenough Burgwyn) belonged to a distinguished New England family and whose father (Henry King Burgwyn) was of New England and southern heritage.[1] The novel captures the internal turmoil and difficulties many, including C.P.E. Burgwyn, must have felt during the war. He lost a brother (Colonel Henry K. Burgwyn) at Gettysburg and another was wounded and captured at Cold Harbor. The book, and much of his other work—both professional and para-professional—are decidedly pro-South.

C.P.E. Burgwyn was born on April 5, 1852, in Northampton County, N.C. Immediately following the Civil War, his family moved to Boston, where Burgwyn attended school, and lived, until 1877. He became a civil engineer who worked for the U.S. Coastal Survey, designed harbor improvements for the federal government, and won the commission for the expansion of Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery—a design compatible with the original 1848 plan by John Notman. He also supervised the installation of Richmond’s first telephone lines. In 1886, Burgwyn worked for the City Engineer (Wilfred Emory Cutshaw) and assisted with supervision of the construction of Richmond’s City Hall. The building, recently renovated, stands on Broad St. and was designed by architect Elijah E. Myers in the High Victorian Gothic style. Burgwyn also worked on several mammoth public works projects along the James River.

The novel takes its name from its final setting: the Huguenot Springs Hotel. Located in Powhatan County, Huguenot Springs is a 12-acre rural property once popular as a summer resort where Richmonders took in the waters at nearby sulfur springs. The original hotel was constructed in 1847-1850 by the Huguenot Springs Mining Company. Curiously, the hotel’s landscape was designed by John Notman—a fact Burgwyn would have known. The landscape was an ample bowling green with a semicircular driveway directly in front of the three-story wood frame hotel with wraparound porches. Cottages located along the carriage lane provided additional accommodations. A very popular location for antebellum socials, balls, and dances, the hotel also served as a Confederate soldier hospital during the Civil War. In the post-war era, the hotel was once again a site of social activity, visited by many. Robert E. Lee and other notable Confederates served on the hotel’s board. The three-story hotel burned down in 1890, and what remains today are the brick outline of its foundation behind the current house, and one extant free-standing cottage.[2]

What compels me to tell you about this is not to discuss political sympathies, nor to debate the book’s literary merit. As an architectural historian and preservationist, I do feel that Huguenot Lovers serves as a primary source providing insight into the thoughts, opinions, and look of Richmond during a period when the city was attempting to rebuild and remarket itself as a rising beacon of the industrialized “New South.” The book embraces ideas from the vanguard in landscape architecture, which would crystalize shortly thereafter in the City Beautiful Movement.

The best example of Burgwyn’s work is Monument Avenue. A National Historic Landmark (NHL), Monument Avenue is regarded as one of the best examples of the City Beautiful Movement. As stated in the NHL nomination, “when a grand avenue as a setting for the Lee Monument was proposed, it appealed to many different desires and goals. A grand avenue could provide a showcase of residences for the wealthy merchants and professionals of Richmond's changing community, lay out a modern civic centerpiece for the Richmond of the New South, and combine forces with the evolving movement to express pride in the ‘Lost Cause.’”[3] Indeed, Burgwyn sings the song of Richmond in this passage, perhaps an attempt to not only expose the Huguenot lovers, but also breathe life into a city hollowed out by the ravages of a fratricidal Civil War.

The engineer leaves us with a vignette:

"In all her ideas of Richmond she had imagined it a low-lying city, surrounded by flat lands and waste woods. Her surprise was great when she found it what it is. This was the city of which she had heard so much and knew so little. This long, broad street, down which the train was passing, was apparently unending, and what a beautiful park, what fine residences, and how bright the sun was reflected from the large windows. Presently the train shot into a tunnel, from which it emerged and soon came upon the long bridge across the James. What a sight to see the water breaking over the rocks and glittering like streaks of light, and how high the train was up in the air; what colossal foundries were underneath, and what a picturesque castle on top of the hill overlooking the river!” (pp. 93-93)

Review the inventory of contents from the lead container found under the Lee monument in Richmond.

—Laura Lavernia

ACHP Program Analyst and GSA Liaison

Former DHR Architectural Historian, Review and Compliance Division

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR's archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

References

[1] “Biography of Collinson Pierrepont Edwards Burgwyn,” Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia (accessed 1/31/2022). https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.php?b=Burgwyn_C_P_E

[2] Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR) Architectural Survey Form, “Huguenot Springs (DHR ID #072-0092)”

[3] Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR). Monument Avenue National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, 1997. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/127-0174_Monument_Avenue_HD_1997_Nomination_NHL-4.pdf. For discussions of Richmond's progressive era, see Michael Chesson, Richmond After the War, 1865-1890 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1981); and Kathy Edwards, Esme Howard, Toni Prawl, Monument Avenue, History and Architecture (Washington, D.C.: HABS, National Park Service, 1992), Chapter 1.