Cornerstone Contributions: Investing in the Confederacy: The Role of Bonds in Funding the Confederacy

How did the Confederacy finance itself? The author details how the Confederate government raised the necessary funds to support its operation and the war effort.

The Confederacy's Need to Raise Revenue

When the Confederacy seceded from the Union, they were confronted with the task of establishing a new government. They needed to act quickly to enact laws and establish offices to manage the affairs of state. Of immediate concern was the need to raise revenue through borrowing, taxation, and printing currency.

The Confederate government turned to issuing bonds and printing currency to generate the revenue needed to run government affairs and fund the war effort. According to one researcher, Confederate bonds accounted for 32% of CSA revenues compared to 60% from printing currency (Weidenmier 1993:2). Imposing taxes was not politically feasible in a newly established country advocating states’ rights, and collecting tariffs from imported goods was impeded by the Union blockade. As a result, taxation accounted for only 8% of the revenue the Confederacy was able to raise.

The Bond

A bond authorized by the Confederate legislature the same month the Confederacy was established in February 1861, was one of the items deposited in the cornerstone box (Figure 1). The first bonds authorized by Confederate legislation were intended to raise $15,000,000 to meet the immediate needs of the new government (Ball 1998:27). Additional bond acts from 1861 through 1864 authorized greater sums to support the war effort (Ball 1998:246-247).

The bond was deposited in the cornerstone box by John F. Mayer who also deposited the adjutant's seal. The first question that comes to mind is who was Mayer? Why did he leave this item in the box? His service records indicate he was a clerk at the War Department in Richmond during the war. He contributed archival material relating to the Civil War on several occasions to the Southern Historical Society (1876-1877) and was noted as being "an industrious collector of Confederate material" (Southern Historical Society Papers 1877:95). He was not only present at the unveiling of the Lee Monument but was also actively involved by pulling ropes when the monument was transported from the railroad station to Monument Avenue (SHSP 1889:253).

The bond depicts the image of a man and woman in the center and a woman standing with a shield (allegorical depiction of Liberty) in the lower left-hand corner. The bond has a value of $100,000, yielded 8% interest, and was issued on March 17, 1864. The bond had an 1871 redemption date, six years after the CSA ceased to exist. This type of bond is considered rare as it is estimated that only 445 were issued and only five in the amount of $100,000 (Ball 1998:42). The large denomination of this bond is unusual as the value of most bonds ranged from $100 to $1,000.

Who invested $100,000, an amount equivalent to $1,776,000 in today's money (CPI n.d.), in 1864 when the South was in dire straits and had lost decisive battles at Gettysburg and Vicksburg? The bondholder is not legible as the ink is smeared due to water damage but the last two legible letters "Co" indicate it was held by a company, not a person. Since the company was able and willing to purchase a $100,000 bond, they must have had a vested interest in the Confederacy. Additional examination of the bond in the future using multi-spectral imaging may reveal the identity of the bondholder.

As with most CSA bonds and currency, this bond was printed by a lithographer in a southern state, J. T. Paterson & Co. of Columbia, South Carolina. Paterson, a Scottish dentist living in Georgia when the Civil War started, was one of twelve known printers of Confederate bonds. According to one researcher, he entered the security engraving business to avoid the Confederate Conscription Act of 1862 because occupations that served the public interest were exempt from conscription (Ball 1998:18).

Other printers of Confederate bonds include an unknown firm in England and the American Bank Note Company of New York. Ironically, the first order for the printing of Confederate bonds was placed with the New Orleans branch of the American Bank Note Company but was actually printed at the American Bank Note Company in New York before war commenced with the bombing of Fort Sumter (Ball 1998:12). After war broke out, US marshals seized the plates used to print the bonds from the New York branch of the American Bank Note Company.

The person who signed the bond, Robert Tyler, Register of the Confederate States Treasury, was the son of U.S. President John Tyler who served in that office from 1841-1845. Before war broke out, Robert Tyler was the head of the Democratic Party in Pennsylvania and after the war, he became the head of the Democratic party in Alabama (Ball 1998:21).

Other Types of Confederate Bonds

What is known about Confederate bonds? The first attempt to categorize them was made in the 20th century with the goal to provide a guide for collectors (Criswell 1980). A more detailed study, involving the examination of tens of thousands of bonds, resulted not only in the publication of a definitive catalog but also the completion of a PhD dissertation from the University of London's School of Economics (Ball 1998). Ball’s research also led to the discovery and study of a large hoard of forgotten CSA bonds that had been stored in a foreign country for over a century.

Confederate bonds depict a variety of images. Most have lithographs of CSA figures (elected officials and cabinet officers) but also include historical American figures (George Washington and Andrew Jackson), monuments, ships, trains, bales of cotton, soldiers, allegorical figures (Liberty, Columbia and Ceres) and other subject matter (Criswell 1980, Ball 1998). The most common figures depicted on Confederate bonds were the first two Confederate States Secretary of the Treasury, C.G. Memminger (Feb 21, 1861-July 18, 1864) and George A. Trenholm (July 18, 1864-April 27, 1865).

The Confederate practice of depicting portraits of contemporary political figures on their bonds and currency differs from the US tradition of never depicting living figures on currency, a practice still held to this day. US coinage in the 19th century relied on Liberty style images and it was not until 1909, when an image of Lincoln was placed on the penny to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth that an exception was made to place a deceased figure on US coinage.

Over three-hundred and sixty varieties of CSA bonds are recognized based on differences in vignettes, their value, or other attributes such as the paper they were printed on. Interest rates on CSA bonds varied from 4% to 8% and the maturation date varied from 1864-1893 depending upon the amount of interest authorized by the Confederate legislature. To provide a sense of other types of bonds issued by the Confederate government a few varieties will be discussed.

The two bonds depicted in figures 2 and 3 have images of Confederate office holders, the President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, and the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury, Christopher G. Memminger. The bond with Davis includes a vignette of Richmond viewed from the west. Both bonds were authorized to fund treasury notes by an act of the Confederate legislature dated February 20, 1863. They yielded 8% interest and were redeemable on the first day of July 1868. These two bonds were signed by Charles A. Rose, the Assistant Register of the Confederate Treasury, who was appointed in 1863 and served until the end of the war (Ball 1998:21). Both bonds have coupons that have been clipped to redeem interest.

Bonds also depict images of Richmond buildings and statues. The Old Customs House in Richmond and the equestrian statue of George Washington are depicted on two bonds (figures 4 and 5). The redemption dates (1868 and 1893) and rate of interest (6% and 8%) differ on the bonds, one of which was authorized by an act dated August 19, 1861 and the other by an act dated March 23, 1863. One bond has coupons that have been removed to redeem the interest and the other has pen cancellations.

Two bonds with military themes: a $500 bond of a Confederate soldier by a campfire (Figure 6) and a $100 bond of a Confederate officer by a tree overlooking the Rappahannock River (Figure 7), are both 7% coupon bonds authorized by the Confederate Congress on February 20th, 1863. They were authorized to fund treasury notes issued from May - December 1863 and redeemable on the first day of July, 1868. They were printed on pink paper by a Richmond lithographer. Both bonds have all the coupons attached indicating that interest was never collected. Since interest was paid in Confederate currency, perhaps the bondholders realized that Confederate currency held little value.

The CSA issued mostly domestic bonds but also collaborated with European countries to market bonds. One of the foreign bonds was backed by cotton which traded mainly in England and the other was a high risk (junk bond) traded in Amsterdam. The cotton bonds were redeemable in cotton during the war but the holder of the bond had to navigate through the Union blockade to receive bales of cotton at designated southern ports. There was a political motivation behind the foreign bonds, especially the cotton bonds, for they provided an incentive for European intervention to support the South.

During the brief four-year history of the Confederacy, monetary reforms were implemented to encourage the conversion of currency into bonds. These reforms also had the effect of increasing the price of goods (Burdekin and Weidenmier 2003:420). The inflation rate in the Confederacy rose to over 9,000% at the end of the war as compared to only 80% for the Union (Ball 1991).

Despite numerous legislative acts to control the fiscal economy, rampant inflation caused social unrest. In March and April of 1863, the price of basic commodities led to bread riots in southern cities, included an organized riot in the city Richmond (Figure 8).

Post-War Speculation and 20th-Century Hoard Discovery

CSA bonds were actively traded on the London and Amsterdam stock markets and their value steadily declined as the war progressed due to CSA military setbacks. The bonds continued to be traded after the Civil War based on speculation that the United States government may partially redeem their value but the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, passed on July 9, 1868, prevented this from happening:

"neither the United States nor any state shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void."

Despite the passing of the 14th Amendment, speculation continued in European markets with offers to buy the bonds for 10% of their face value during the period 1879-1884 (Ball 1998:9). At that time, there was a Confederate depositary in Europe that was still receiving assets after the war and a Confederate Bond Holder's Committee was established in England to redeem the bonds. Bonds flowed into Great Britain from southern states during this period (Ball 1998:10).

Whenever there is fiscal speculation, there is also fraud. The speculation on Confederate bonds by European countries after the war led to the manufacture of counterfeits. The forged bonds were not well made, had forged signatures, and were printed on wood pulp paper that became brittle over time (Ball 1998:234). Most of the counterfeit bonds appear to be manufactured in the Netherlands as many have Dutch tax stamps.

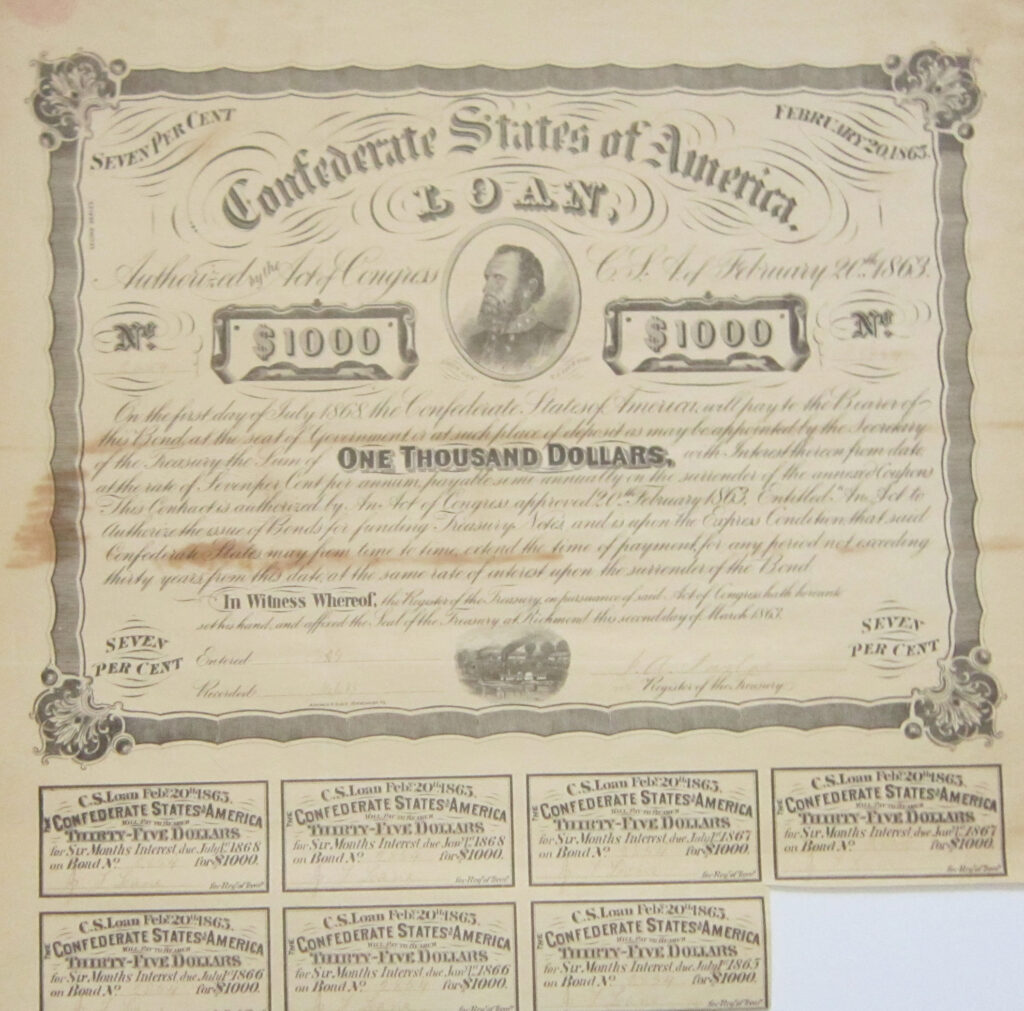

The following figures depict an authentic (Figure 9) and a counterfeit (Figure 10) $1,000 bond of Stonewall Jackson. This type of bond is believed to have been forged more so than other bonds (Ball 1998:9).

Once it was finally determined that the bonds had no monetary value, many if not most were discarded. However, more than 100,000 unclaimed and unredeemable CSA bonds, held in a vault by the Coutts Bank of England for over a century, were rediscovered and sold to an American numismatic company in the 1980s (Ball 1998:10; Heathcote 1997). Today they sell and trade on the open market as Civil War memorabilia.

—Robert L. Jolley

Department of Historic Resources

Archaeologist for the Northern Regional Preservation Office

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR's archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

References:

1998 Comprehensive Catalog and History of Confederate Bonds. BNR Press, Clinton, Ohio.

2000 The Politics of Selective Default: The Foreign Debts of the Confederate States of America. Department of Economics, Claremont Mckenna College.

Ball, Douglas B.

1991 Financial Failure and Confederate Defeat. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

Burdekin, Richard C. K. and Marc D. Weidenmier

2003 Suppressing Asset Price Inflation: The Confederate Experience, 1861-1865. Economic Inquiry: 41 (3):420-432.

CPI Inflation Calculator

n.d. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed March 6, 2022.

Criswell, Grover C.

1980 Confederate and Southern States Bonds. Second Edition. Criswell Publications.

Fold3

https://www.fold3.com/. Accessed February 23, 2022.

Heathcote, Graham

1987 U.S. Civil War Bonds Found in London Vault. AP News, October 31, 1987.

Southern Historical Society Papers

1877 Southern Historical Society Papers: Volume 3: 95.

Weidenmier, Marc. D.

1993 Money and Finance in the Confederate States of America. In Explorations in Economic History 30 (1): 352-376.