Cornerstone Contributions: Creating Monument Avenue

The story of the creation of Monument Avenue consists of several intertwined subplots: how the avenue came to exist, how it became an avenue both of monuments and of houses, and how mythmaking influenced which Confederates deserved monuments. Although this story is closely connected to the Civil War, the street evolved amid efforts to expand the city in the decades after the war. Making it an avenue of Confederate monuments between 1890 and 1929 was part of a deliberate reinterpretation of Southern history half a generation after the conflict ended.

Creating the Avenue of Monuments

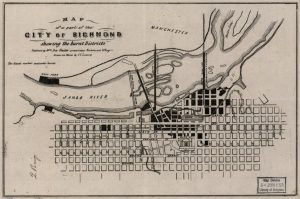

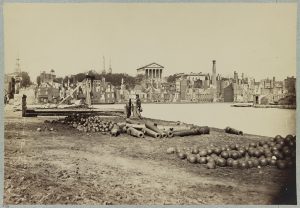

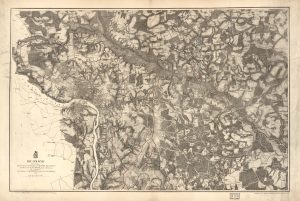

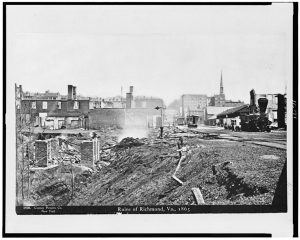

During the Civil War, Richmond and its surroundings, as with many other Southern cities and towns, suffered significant infrastructure damage. Federal troops burned railroad bridges and tore up tracks outside the city to cut Confederate supply lines. Roads and farm lanes were damaged or destroyed when Confederate engineers constructed three lines of earthworks and artillery batteries across them to defend Richmond. Near the end of the war, when the Confederate army burned several warehouses between Capitol Square and the James River on April 3, 1865, and the flames spread, the resulting Richmond Evacuation Fire destroyed much of the downtown business district. Fortunately, most of the residential areas survived unscathed.

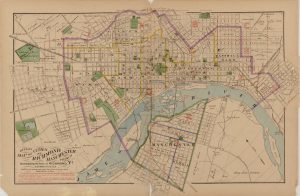

As the city quickly rebuilt and businesses reopened, new residential neighborhoods were developed, mostly to the north and west. For decades before the war, after the capital was moved from Williamsburg to Richmond in 1780, many members of Richmond’s upper class resided either near the Capitol or on Church Hill, to the east across Shockoe Creek. By the 1840s and 1850s, the area just west of Capitol Square was gaining in popularity, especially several blocks along Franklin Street, which terminated at Monroe Park, just west of Belvidere Street. After the war, Franklin Street and neighboring streets were extended west to present-day Lombardy Street, about one and a half miles from Capitol Square. Richmond’s elite (including newly prosperous merchants) continued to build new houses along Franklin Street.

At the war’s beginning, then, the western edge of the city’s web of streets was Monroe Park. Farms lay beyond. During the fifteen years following the end of the war in 1865, the streets resumed their westward advance to the vicinity of Lombardy Street and Richmond College. There, the urban streetscape largely ended, and the view toward the setting sun was of farmlands, stretching for miles. Immediately west of the college lay a large tract belonging to William C. Allen.[1]

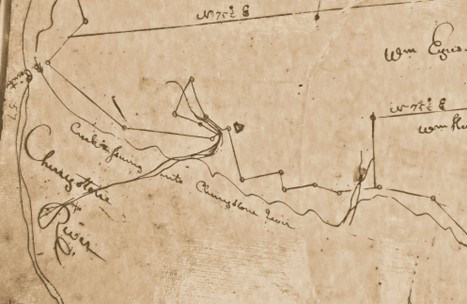

Allen had come to Richmond about 1810 with his mother and was apprenticed to a bricklayer. Through hard work, he gradually became a successful antebellum contractor and developer, amassing a substantial fortune, tracts of land, and city lots before he died in 1874, aged 81. Among his heirs were his son Otway S. Allen and three daughters (Mary C. Sheppard, Bettie F. Gregory, and Martha A. Wise). They inherited Allen’s tract, which he had acquired as a long-term investment, that extended from Lombardy Street three blocks west to present-day Allison Street. In part because of the economic panic of 1873 and its aftermath, Allen’s heirs were slow in developing plans for the tract. Finally, in 1887, Otway Allen had the city engineer, Collinson Pierrepont Edwards Burgwyn[2] (commonly and understandably referred to as C. P. E. Burgwyn), draw a plan for an extension of Franklin Street through the tract to its western end at Allison Street. The extension was drawn as a broad avenue intersected by a similarly wide north-south street named Allen Avenue. At the intersection, named Lee Place, was a large circle, and the avenue was named Monument Avenue. The drawing was attached to a plat that accompanied a deed of the circle to the Lee Monument Association; the avenues and streets were deeded to “the public,” meaning the city and Henrico County. The Allen heirs retained the rest of the tract for future development.[3]

The Lee Monument Association was formed from two earlier groups—one male, one female—in March 1886. Governor Fitzhugh Lee, a former Confederate general and nephew of Robert E. Lee, headed the new organization. For the site of the monument, the women preferred Hollywood Cemetery, where many Confederate dead were interred, while the men advocated for various locations including Capitol Square, Monroe Square, Gamble’s Hill, and Libby Hill. Two factors turned the tide in favor of the future Monument Avenue. First, it was on open and undeveloped land located in an area of impending growth, and second, it was just north of Robert E. Lee Camp Number One, the home established in 1883–1884 for destitute Confederate veterans. So, in 1887, Burgwyn endorsed the location and Otway Allen deeded the circle to the association.[4]

Although it took three more years to create the Lee monument, by June 1887 the association had selected a design and a sculptor, the renowned French artist Marius-Jean-Antonin Mercié. On October 27, 1887, the association held a parade of Confederate veterans who marched west from downtown Richmond to the circle to dedicate the cornerstone. Speeches were given, the cornerstone was laid, and the site was readied for the monument. In 1888, the Allen heirs in cooperation with Burgwyn produced a map of the area that showed Monument and Allen Avenues with their medians and the lots laid out along the streets from Broad Street south to Park Avenue. Monument Avenue was now ready for development.[5]

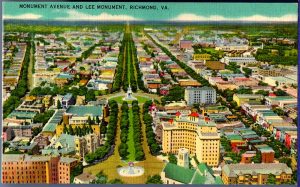

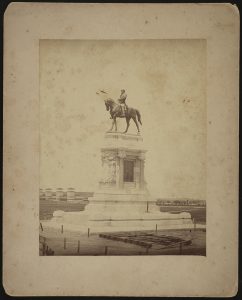

The development, however, was slow to come. No houses had been constructed there by the time the completed Lee monument was at last unveiled and dedicated on May 29, 1890. And then, in 1893, the financial panic of that year was followed by about a decade of slow growth. The first house, located at 1601 Monument Avenue, was completed in 1894 (it was demolished in 1978 for a parking garage). By the time Otway Allen died in February 1911, however, about sixty houses had either been built or were under construction. Monument Avenue had finally become the neighborhood for Richmond’s elite, living in houses designed by such notable architects as William Lawrence Bottomley, W. Duncan Lee, Carl Lindner, and Max E. Ruehrmund, among others. The avenue was extended west over sixty years following the Lee Monument dedication, stretching to Roseneath Road and beyond; house construction on the street between those two points was largely complete by the 1940s.[6]

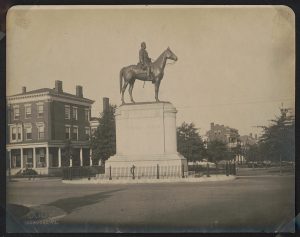

More monuments followed Lee’s as prosperity returned and funds were raised. The next one erected, for Major General J. E. B. Stuart, was dedicated on May 30, 1907. It was located in a circle a block east of Lee’s, at the intersection of Lombardy Street and Monument Avenue. Originally, the Stuart Monument Association had hoped to place it in Capitol Square, but the city’s board of aldermen insisted that it go elsewhere. The design, executed by Frederick Moynihan, was based on a concept drawn by Captain M. J. Dimmock, in turn based on the 1874 statue of General Sir James Outram in Calcutta, India. Both statues showed the riders reining in spirited horses with one front leg in the air, as the rider twisted in the saddle to look at the action behind him. The Stuart statue was in marked contrast to that of Lee, calm and unperturbed on his steady mount.[7]

Four days after the Stuart Monument unveiling, the Jefferson Davis Monument was dedicated on June 3, 1907. The Jefferson Davis Monument Association had been formed in December 1889 ten days after the former Confederate president died in Mississippi. Various proposals were put forth but died for lack of funds, including a massive domed temple and a huge arch, to be placed in Monroe Park and at Broad and 12th Streets respectively. Finally, in 1903, the United Daughters of the Confederacy approached the Richmond city council to suggest a Monument Avenue site four blocks west of the Lee Monument at a street renamed Davis Avenue. The council approved, and the UDC engaged local talent—architect William C. Noland and sculptor Edward V. Valentine—to design the monument. The final product, oriented east toward Capitol Square, depicted Davis giving a speech with a tall column immediately behind him, topped with a female statue of Vindicatrix. To the rear of both is a semicircular “screen” of thirteen smaller columns. The monument presents the Lost Cause in full flower, with inscriptions in both Latin and English referencing “the Rights of States.” The speeches delivered at the dedication likewise pounded the message home.[8]

During the war, Confederate authorities had erected three defensive lines to protect the city: the Outer, Intermediate, and Inner Lines. All but the Inner Line consisted of miles of earthworks with intermittent artillery emplacements; the Inner Line featured large earthen forts or batteries for multiple cannons but no earthworks to connect the batteries. Battery No. 10 was constructed astride the future route of Monument Avenue. Like almost all of the other batteries and earthworks surrounding the city, it gradually disappeared as farmers re-leveled their torn-up fields and pastures. By the time Monument Avenue came into being, only a hump of earth remained on the street’s south side, and soon it was gone, too. In 1915, the Confederate Memorial Literary Society and the city erected a miniature monument (in comparison to the others) to mark the site, half a block east of the Davis Monument in the median at about 2319 Monument Avenue. The small memorial consisted of a cannon aimed west and mounted on a short pier of stone and concrete, with a plaque.[9]

The next monument, which commemorated Lieutenant General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, was dedicated on October 11, 1919. One might wonder why it took so long for the first major hero of the Confederacy during the war to claim his place on Monument Avenue at Boulevard (now Arthur Ashe Boulevard). Several statues of Jackson had already been erected, including one in Capitol Square; however, all presented him standing, while this was the first to show him mounted. The Jackson Monument Corporation was founded at the Lee Camp on November 29, 1911. Sculptor F. William Sievers, known for his ability to create exact likenesses, was chosen in 1915 to create the monument. Instead of Little Sorrel, Jackson’s favorite horse, Sievers used a Thoroughbred named Superior as his horse model, probably because its proportions worked better on the twenty-two-foot-high pedestal. Appearing as calm as Lee, Jackson faced north, seemingly awaiting the battle to come.[10]

The last of the Confederate monuments installed on Monument Avenue was dedicated to Matthew Fontaine Maury, "The Pathfinder of the Seas.” Born in Virginia in 1806, Maury joined the U.S. Navy in 1825, sailed around the world, and wrote a treatise on navigation. A knee injury suffered in 1839 disabled him from further sailing; he was appointed first head of the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., in 1842. Far from the sea, he undertook the mapping of stars and oceans, seabeds and land masses. He is considered the father of scientific oceanography and hurricane forecasting, the focus of the future U.S. Weather Bureau. After Virginia seceded, he served in the Confederate Navy, invented an electric “torpedo” or mine to protect Southern harbors, and traveled abroad as a Confederate government agent. Returning to Virginia after the war, he taught at Virginia Military Institute until he died in 1873. Ironically, although Maury’s oceanographic discoveries gained him worldwide fame, he was almost unknown in America outside the naval and scientific spheres. Maury enthusiasts raised money for a monument, F. William Sievers sculpted it, and it was unveiled three blocks west of the Jackson Monument, at the intersection with North Belmont Street, on November 11, 1929. The monument, like the man himself, was very different from those dedicated to Confederates known for their political or military accomplishments. Maury was seated, deep in thought, while behind and above him several storm-battered allegorical figures strain beneath the weight of a globe. As depicted in the monument, Maury’s scientific accomplishments rendered his Confederate associations almost incidental, although the United Daughters of the Confederacy contributed to the monument fund and helped raise money for it.[11]

The Confederacy and its heroes, then, were well represented on Monument Avenue, beginning with the Lee monument in 1890 and continuing with the memorialization of Stuart (1907), Davis (1907), Jackson (1919), and Maury (1929). Each monument presented an idealized image of its subject; and each was erected during a period when the war and its causes, like the Confederate defeat and the utter destruction of the antebellum way of life, were receding into history along with the dwindling number of Confederate veterans. During the same period, however, just as the heroes gained mythic status in Southern memories, so too did a new way of “remembering” the causes, course, and conclusion of the war, as well as its aftermath. It was known as the myth—or cult—of the Lost Cause.

The Path from States’ Rights to Secession and War to the Lost Cause

The pedestals and statues erected on the avenue have been called monuments to the myth of the Lost Cause, in part because the street and its monuments evolved simultaneously with the myth. To understand the Lost Cause, it is first necessary to understand what led up to it. In other words, to understand the progression, especially in the South, from states’ rights to secession and war, and finally to the end of enslavement and the postwar period of Reconstruction.

The political philosophy of states’ rights—that a state could countermand or “nullify” federal laws that it considered an encroachment of central government power—dates to at least the 1780s and the adoption of the Constitution. The first states’ rights or nullification crisis occurred during the War of 1812 when a few New England states threatened secession over the war, which they opposed because Great Britain was a major trading partner. The crisis ended with the war’s conclusion and did not return as a serious threat to unity until the 1830s and 1850s.

Meanwhile, during the first half of the nineteenth century, support for the abolition of enslavement grew in Europe and in North and South America. Haiti (1804), Mexico (1829), Great Britain (1834), France (1848), and several South American countries were among those that abolished the institution. As the abolition movement grew in the Northern United States, so too did the countermovement in the South to preserve the institution, often claiming that it was the “states’ right” to repudiate abolition and enforce enslavement.

After the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), the United States expanded westward and the debate over enslavement in the territories and new states intensified. The delicate balance of U.S. Senate power between the Northern “free states” and the Southern “slave states” would collapse if a majority of the new states in the West were admitted to the Union as either “slave” or “free.” In 1854, U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois proposed that the voters in each new state decide for themselves whether to allow enslavement or not. Although his proposal (approved by Congress as the Kansas–Nebraska Act) seemed the very epitome of the states’ rights principle, the South opposed it because antislavery majorities in the new states could upset the balance in the Senate. In the North, opposition to permitting enslavement at all in new states caused the collapse of the Whig Party and the rise of the Republican Party. And then, in 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the Dred Scott case that enslavers could recapture their self-liberated “property” in free states, further enraging abolitionists.

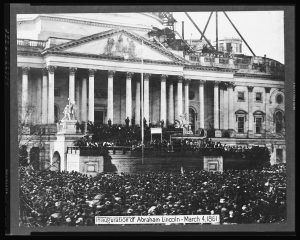

When the Republicans, endorsing an antislavery platform, nominated Abraham Lincoln for president in 1860, and Lincoln won, the Southern enslaving states rejected the result. Once again embracing their interpretation of states’ rights, they began to secede from the Union. But why, specifically, were they seceding?

As historian Charles R. Dew explains in his book Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001), the reason was simple and clearly stated: to preserve enslavement from the threat of abolition. South Carolina, the first state to secede (December 20, 1860), explained its rationale succinctly in a pamphlet published by the secession convention (Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina). Secession was necessary, it explained, because “an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the Institution of Slavery has led to a disregard of their obligations” to capture and return “fugitive slaves” to their owners.[12]

The secession commissioners, sent from Deep South states to persuade the Upper South and border states to secede, likewise were clear as to the states’ motivation. On February 18, 1861, for example, two commissioners addressed the Secession Convention in Richmond, held at the Mechanics’ Institute Hall at 9th and Bank Streets. Commissioner Fulton Anderson of Mississippi proclaimed that the Lincoln administration’s goal would be “the ultimate extinction of slavery.”[13] Commissioner Henry L. Benning of Georgia made his state’s reason for Southern secession as plain as the South Carolina declaration: “a separation from the North was the only thing that could prevent the abolition of her slavery.”[14] The message was delivered clearly, both in Virginia and in other Southern states, that secession was the only way to preserve enslavement.

One reason to preserve it was economic: enslaved men, women, and children were the second largest capital investment in the South, next to the land itself. But there were other, more emotional reasons that the secession commissioners collectively iterated, that abolition would create a “nightmare world”:

A South humbled, abolitionized, degraded, and threatened with destruction by a brutal

Republican majority. Emancipation, race war, miscegenation—one apocalyptic vision

after another. The death throes of white supremacy would be so horrific that no self-respecting

Southerner could fail to rally to the Confederate cause, they argued. Only through disunion

could the South preserve the purity and ensure the survival of the white race.[15]

Then came March 1861 and Lincoln’s inauguration, followed by failed negotiations and the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter, which ended in the fort’s surrender on April 14. Lincoln called for volunteers to suppress the insurrection, and soon war began in earnest. Over the next four years, the Confederate states followed a strategy that they hoped would end in victory for their side. Not a military victory in which their armies would crush their opponents, for the Northern states were too superior in numbers of men and quantities of war matériel, but a political victory that would result in the Southerners being left to go their own way, with enslavement intact.

For a precedent, the Confederates could look to General George Washington’s strategy in the American Revolutionary War. Washington could not hope to crush the British Army, arguably the most powerful such force on the planet. What he could do, though, was avoid a crushing defeat, maintain his army in the field to strike hard whenever possible, prove the viability of the so-called “United States” sufficiently to attract foreign recognition and military support, and succeed finally in wearing down the United Kingdom’s desire to keep fighting to no end, so that Britain would at last give up and let the colonies go. This approach ultimately succeeded, and seven years after the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the British yielded with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, and the United States became an independent nation.

This became the Confederate strategy, especially in Virginia after General Robert E. Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia. In constant consultation with Confederate president Jefferson Davis, Lee fought a largely defensive war, avoiding any definitive defeat while inflicting several hard blows on Federal armies, invading north across the Mason-Dixon Line twice in hopes of gaining foreign recognition, and sustaining his army as a fighting force until surrendering at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. In contrast with Washington’s strategy, however, the Confederate strategy failed. No foreign country ever recognized the Confederate States of America. Lee's invasions—culminating at Antietam and Gettysburg—failed both diplomatically and militarily, inflicting losses on his army from which it never recovered. General Ulysses S. Grant’s campaigns of 1864 and 1865 further wore Lee’s army down while the Federal numbers increased. Lee’s army, depleted by casualties and desertions, was a shadow of its former self at Appomattox. As a measure of Confederate desperation, only a few months earlier, Lee’s catastrophic losses forced the Confederates to do what had long been unthinkable: recruit enslaved men to fight in exchange for freedom. That scheme failed, too.

Both militarily and politically, the Confederates lost the war to preserve enslavement. Soon after the fighting started, Lincoln had realized that even if the North won the war to reunite the Union, little would have been gained if the institution still existed in the United States. Abolition became a military as well as a political necessity. After the Union victory at Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln issued a carefully worded preliminary Emancipation Proclamation (to take effect January 1, 1863) that announced the liberation of enslaved persons in states or parts of states still fighting for the Confederacy. The Proclamation in effect eliminated enslavement in areas outside Union military control but left it intact in areas that it did control. But it put the United States on the side of abolition, which further dissuaded England and other foreign countries from recognizing the Confederacy, it directly attacked the Confederacy’s principal reason for secession, and it authorized Black men to serve in the army and navy, further inducing them to flee to Union lines in increasing numbers to deprive the Confederates of their labor.

By the end of the war, large portions of the South lay in ruins—buildings burned, railroads and bridges destroyed, and farms deserted. Most important, the enslavement-based Southern way of life, its social system, and white supremacy were destroyed or heavily damaged, at least momentarily. Instead of merely ordering the enslaved around, white southerners were reduced to the indignity of having to negotiate with them for their labor. United States Army troops occupied the South, in large part to protect the formerly enslaved persons as they transitioned to freedom. Military and political Reconstruction soon upended the social system even more, offering education to Blacks, extending suffrage to Black men, and even encouraging them to campaign for elective offices. In almost every way imaginable, the “nightmare world” that the secession commissioners had predicted had arrived. The Confederacy had failed on every front with a vast cost in lives and fortunes.

For many white Southerners, it was far too much to bear. Counter-Reconstruction efforts, including the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, lynching, and segregationist Jim Crow laws, quickly emerged. To further compensate for their losses, white Southerners also began to create and subscribe to a myth that rewrote the history of secession and the war and assuaged to a degree the catastrophic failure of the Confederacy. It was called the Lost Cause.

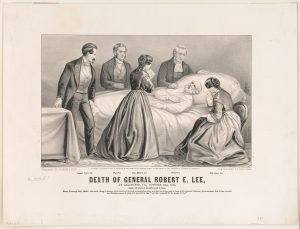

The phrase originated as the title of a book about the war from the Southern point of view, Edward A. Pollard’s tome The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates, published in 1866. The book began a reinterpretation of the war and its causes that produced six tenets or assertions. First, that secession caused the war, not enslavement. Second, that enslaved persons were faithful to their masters and the Confederacy and unprepared for freedom. Third, that the Confederacy lost the war only because of the overwhelming superiority of the North in men and resources. Fourth, that Confederate soldiers were universally brave and saintly. Fifth, that Robert E. Lee was the saintliest of them all, the epitome of Southern manhood. And sixth, that Southern women were all loyal to the Confederacy and sanctified by the sacrifices of their men. Each of the assertions contained at least several grains of truth, but taken as a whole, the myth or theory was contrary to the facts of history.[16]

First, the preservation of enslavement in the face of a perceived abolitionist threat prompted Southern secession, as the secession commissioners candidly stated; the war began when the secessionists attacked Fort Sumter and Lincoln called for volunteers to suppress the rebellion. Second, soon after the war began, enslaved persons fled in droves to the Union lines and freedom, as Federal officials refused to return them to their owners, and after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, approximately 200,000 Black men enlisted. At least 60 percent of Virginia’s enslaved adult males escaped from bondage during the war. Third and fourth, although Union superiority in men and resources obviously played a role in grinding down the Southern armies, so too did desertions, soldiers failing to return from furloughs, and illness. Every army has its problems with cowardice and desertion, and the Confederate army was no different. Fifth, Lee himself would have declined the label of “saint,” or of the perfect general (several modern historians have offered mixed reviews of his generalship). He did, however, maintain his army as a fighting force until the end, and earned the admiration and devotion of his soldiers. Finally, although it was claimed that during the war all white Southern women as well as men supported the Confederacy, this in fact was not the case. Unionists were plentiful although many were quiet about it depending on their local situations. In the Upper South especially, there was a bloody but often overlooked “war within the war” featuring divided families, guerilla attacks, and civilian bushwhackers. Some of the fighting had less to do with secession or unification and more to do with the settling of old scores. Generally, support for secession was lower in mountainous areas, which had smaller populations of enslaved persons.[17]

During the war, women on both sides of the conflict formed organizations to support their men in several ways. Women raised money, sent food and clothing to the troops, nursed the sick and wounded, accompanied the armies as cooks and seamstresses, and in some cases disguised themselves as men and served in the ranks. After the war, women again led movements to support veterans, especially in the South. The U.S. government funded and created national cemeteries to inter the Union dead; pensions and soldiers’ homes for Union veterans; and a program for giving amputees artificial limbs. Former Confederates, of course, were not eligible for such benefits at federal taxpayer expense, so Southern women formed societies to promote and support cemeteries, state pensions and homes, and artificial limb programs. They also formed organizations that encouraged and advanced the memorialization of the Lost Cause and Confederate heroes such as Lee, Stuart, Jackson, Davis, and Maury.

The avenue, the monuments, and the Lost Cause, then, all developed and evolved at the same time over several decades. First came the veneration of Lee and the construction of his statue in 1890, when many Confederate veterans still lived and the organizations that supported them during the war continued to do so. And then, as the numbers of old soldiers dwindled, the descendant organizations—the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy—aggressively supported and encouraged the Lost Cause myth, securing its place in history books, public celebrations, and (with the help of sympathetic lawmakers) in laws and the new state constitution of 1902. The Constitution, combined with Jim Crow laws, effectively removed Blacks from public life, driving them from the polls and ensuring white dominance. The monuments epitomized this victory and the myth that supported it.

A Final Question

What would Lee himself have thought of his monument and the cult of hero-worship and mythology that it initiated? It is not a far reach to conclude that he would have disapproved of it. He was frequently quoted as admonishing his former soldiers to be good citizens of the reunited country and not to harbor ill will or to say or do anything that would promote sectionalism. When he was offered the presidency of Washington College in 1866, he hesitated to accept, concerned that his name might attract bad publicity to the college. That same year, he declined the request of a baseball club in Richmond to name itself for him. A year before he died in 1870, Lee wrote a letter regarding a proposal to erect granite monuments on the Gettysburg battlefield, to illustrate the movements of the armies. Asked to participate in the effort, Lee declined, with the following comment: “I think it wiser moreover not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the example of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife and to commit to oblivion the feelings it engendered.”[18]

Lee died twenty years before his statue was erected and the Lost Cause took hold on Monument Avenue. It is interesting and ironic that—although he may have changed his mind had he lived—Lee’s opinions were in opposition to what occurred, and why it occurred, on this grand avenue.

– John Salmon

Historian

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR’s archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

[1] Kathy Edwards, Esme Howard, and Toni Prawl, Monument Avenue: History and Architecture (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, Historic American Buildings Survey, 1992), 26–27.

[2] For more information about Collinson Pierrepont Edwards Burgwyn read about the book he wrote which was placed in a lead box under the Lee Monument here: https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/news/virginia-is-for-huguenot-lovers/

[3] Ibid., 14; Sarah Shields Driggs, Richard Guy Wilson, and Robert P. Winthrop, Richmond’s Monument Avenue (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 99–101.

[4] Driggs et al., Monument Avenue, 29–31.

[5] Ibid., 34–35.

[6] Ibid., 100–101.

[7] Ibid., 55–63.

[8] Ibid., 64–74.

[9] Ibid., 67–68.

[10] Ibid., 74–79.

[11] Ibid., 79–87.

[12] Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina on Archives.org website, https://web.archive.org/web/20170808015740/http://teachingushistory.org/pdfs/DecImmCauses.pdf, accessed Feb. 25, 2022.

[13] Charles R. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001), 62.

[14] Ibid., 65.

[15] Ibid., 58.

[16] Caroline E. Janney, “The Lost Cause,” on Encyclopedia Virginia website, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/lost-cause-the/, accessed Feb. 28, 2022.

[17] Ibid. See “U.D.C. Catechism for Children (1904)” on Encyclopedia Virginia website, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/u-d-c-catechism-for-children-1904/, accessed Mar. 3, 2022, for the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s summary of the Lost Cause myth; see “Slavery during the Civil War” on Encyclopedia Virginia website, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slavery-during-the-civil-war/, accessed Mar. 3, 2022, for analysis of the numbers of enslaved persons who self-emancipated to Union lines during the war; see “Unionism in Virginia during the Civil War” on Encyclopedia Virginia website, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/unionism-in-virginia-during-the-civil-war/, accessed Mar. 3, 2022.

[18] Emory M. Thomas, Robert E. Lee: A Biography (New York: W. W. Norton & Sons, 1995), 383, 392; Lee wrote the letter about the battlefield monuments to Hon. D. McConaughy, Lexington, Aug. 9, 1869, Lee Papers, Washington & Lee University.