Cornerstone Contributions: Black Richmonders, the Lee Monument, and the Lost Cause Redux

Throughout America’s long history, someone’s heroes are often someone else’s villains. This guest blog is an historical overview of Black Richmonders’ reactions to the Lee Monument’s 1890 dedication ceremonies in the context of the racial times and the Lost Cause as a sociopolitical force. At the intersection of the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries, as communities reassess who and what they memorialize, Confederate monuments require meaningful forms of redress to old grievances. Efforts to banish such monuments from public spaces reflect conflicted memories of what some historians characterize as “The War that Never Ended.”

“The Southern White Folks Is On Top”

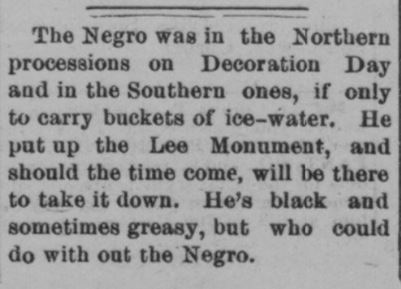

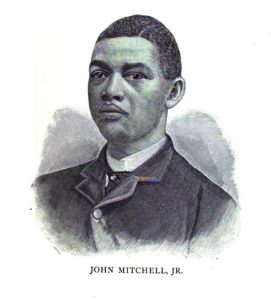

On Confederate Decoration (Memorial) Day, May 29, 1890, twenty-five years after the Confederacy’s defeat, during the unveiling of a gigantic equestrian statue of General Robert E. Lee in what was then empty farmland on the outskirts of Richmond, Virginia, “an old colored man, after seeing the mammoth parade of the ex-Confederates . . . and gazing at the rebel flags, exclaimed, ‘The Southern white folks is on top—the Southern white folks is on top!’” Others expressed disdain instead of despair. Richmond Planet editor and ex-slave John Mitchell Jr., was one of three Black city council members who voted against a $7,500 city appropriation ($209,000 in 2022 dollars) for the ceremonies. Among the few Richmond blacks who publicly ridiculed “Rebel flags,” Mitchell’s scathing front-page editorial reminded readers “these emblems of the ‘Lost Cause’ . . . had been perforated by Union bullets.” He continued: “The South may revere the memory of its chieftains. It takes the wrong steps in so doing, and . . . serves to retard its progress in the country.”

Mitchell’s March: “We Are American Citizens”

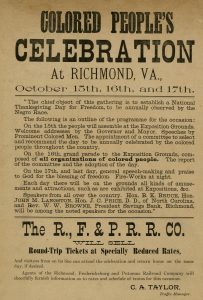

Five months after the Lee unveiling and unintimidated by Confederate veterans “from New York to Texas,” Planet editor John Mitchell countered with a massive two-mile long Emancipation Day parade in Richmond on October 16, 1890, which he led on horseback as chief marshal. Five thousand Black marchers representing forty civic, business and fraternal organizations were accompanied by bands and militia. The parade concluded with a public meeting and speeches before an audience of ten thousand. “We are American citizens,” declared renowned orator Reverend Joseph Charles Price, president of Livingston College, North Carolina, a black Christian school. “When the white people go back to Europe then we will go back to Africa.” John Mercer Langston, less than a month in office as Virginia’s only Black congressman, urged political participation in the post-Reconstruction South: “They say this is a white man’s government [but] I am here to tell you that it is a black man’s government as well.”[2]

Unable to prevent the parade, whites’ intransigence thwarted plans for an artillery salute at Capitol Square. “Citizens of African descent” had petitioned Governor Philip Watkins McKinney for this as “commemorative of our emancipation,” but he denied their request as “it has not been the custom for the executive to order salutes.” The organizers’ executive committee retorted they did not need whites “to fire any salutes for them, they would fire their own.” Other whites, not questioning the color of African American dollars, saw entrepreneurial opportunities. Reduced-rate round-trip tickets offered by the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad Company assured prospective passengers they could attend and return home the same day.[3]

The Lost Cause Defined

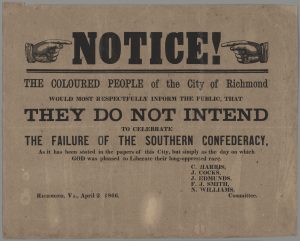

Early postwar public commemorations of the Civil War/the War Between the States occurred in a backdrop of social and racial tensions. Black Richmonders’ April 3, 1866 Emancipation Day parade marking the first anniversary of the city’s capture by Union troops prudently dissociated the South from slavery. Responding to rumors by nervous whites, a “Colored League” explained the commemoration as “the day on which God was pleased to Liberate their Long-oppressed race” and issued broadsides denying Blacks were celebrating the “failure of the Southern Confederacy.” The parade peacefully concluded at the State Capitol grounds where an audience of 15,000 were addressed by black and white speakers.[4]

This event coincided with the beginnings of the Lost Cause ideology as conceptualized in Edward Pollard’s The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates (1866), a sixty-word-titled tome of nearly eight hundred pages, and The Lost Cause Regained (1868). The Richmond Examiner’s wartime editor and a critic of Confederate president Jefferson Davis, Pollard had been imprisoned at Fort Monroe, Virginia, after his 1864 capture while attempting to reach Great Britain by running a Union naval blockade. Curiously, for all his championing of the South, several of Pollard’s books were published in Philadelphia and New York City.

Pollard conceded secession as unconstitutional but insisted slavery had made the South a “noble type of civilization.” He endorsed white supremacy, asserted Black racial inferiority, denounced their suffrage and citizenship, and opposed federalized Reconstruction. Some Southerners questioned whether slavery and secession were ever divinely sanctioned as the cornerstones of their cause; Jefferson Davis (whose memoirs concluded with “the Union, Esto perpetua”--‘may it endure forever’) told a clergyman “the failure of our righteous cause rendered doubtful the government of the world by an overruling providence.”[5]

Southerners have long downplayed slavery as the war’s cause and lynching and legalized racism as its horrific twentieth century perpetuations. The Lost Cause is the mother of all cultural wars, spawning holidays, commemorations, pseudo-nationalistic organizations, publications, radio and television programming, and movies. Its false nostalgia and distorted mythology rationalized Confederate defeat; its zenith (1880s-1920s) accompanied enactment of racist laws in the Jim Crow South, followed by a resurgence during the Civil War Centennial (1957-1965) and the American Civil Rights Movement (1950s-1960s).

Among the Lost Cause’s tenets: the South did not win the war but should have; the failure to establish a slavery-based nationhood as regrettable; veneration of Confederate “heroes” as justified; Reconstruction as federal oppression, thus vindicating the reestablishment of white-supremacist state governments (often at the expense of citizens of color). The Library of Congress defined it as an “idealization of a society and culture perceived as noble and civilized but doomed by overwhelming forces—an enduring myth to ameliorate defeat” with “nostalgia for Southern gallantry and the prewar status quo.” One Pulitzer Prize-winning historian belittled it as “a cult of the dead”; a twenty-first century historian cheekily remarked “white Southerners were more unified in looking back at the Civil War than they had been during it.”[6]

Dead Confederates on Horseback

According to historians, the difference between monuments and memorials is that monuments are commemorative statuary or buildings while memorials comprise everything else (historical markers, parks, ships, streets, place names) of events and persons deemed worthy of honored remembrance. Confederate monuments valorize and summarize what I define as ‘the seven S’s’ of Southern history’: sanitizing of Confederate history; sanctity of white womanhood; secession; segregation; slavery; States’ Rights extremism; and white supremacy.

The violent August 2017 Unite the Right rally against the removal of Charlottesville statues of generals Robert E. Lee (1924) and Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson (1921) resulted in their white supremacist defenders inadvertently provoking their subsequent removal. Were it not for this ‘Battle of Charlottesville’ these and similar statues would still be in their public spaces. The rally resulted in the death of one anti-racism protestor, dozens injured, and subsequent removal of thirty-seven similar monuments around the nation by year’s end. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, Virginia has the most such monuments and as of 2021--for the second year in a row--has removed the most such monuments of any state, followed by Texas and Florida.[7]

A Charlottesville cemetery monument epitomizes the Lost Cause mindset: “Fate Denied Them Victory But Crowned Them With Glorious Immortality.” Confederate statuary in bronze, granite or marble are Lost Cause idolizations and, like battlefields, favored destinations of neo-Confederate pilgrimage. Union/Northern military monuments are triumphalist; Confederate/Southern statues symbolize unapologetic defiance and typically face north, ready to hurl back their foes 160 years after the Civil War.[8]

Slavery’s Sword: General Lee and African Americans

Robert E. Lee is the subject of more Confederate monuments than anyone else; “as America’s most honored traitor, his image is indelibly etched across the landscape and his reputation is based largely on national gratitude for what he did not do: win Confederate independence and his refusal to endorse guerrilla resistance against restored federal authority.” A product of his region (the Slave South), social class (First Families of Virginia), gender (white male patriarchism) and race (white supremacy), Lee’s loyalists consider “Marse Robert” a benevolent, reluctant slaveholder and too much of a gentleman to have been a racist.

One quirky legal matter ironically made him a reluctant emancipator. Three days before Abraham Lincoln’s January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, Lee dutifully complied with the provisions of the antebellum last will of his father-in-law George Washington Parke Custis by manumitting 194 slaves whom Custis ordered freed within five years of his death (1857); none took “Lee” or “Custis” as their new surnames.

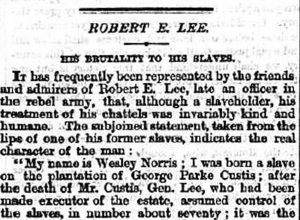

There are a few surviving first-hand accounts by African Americans personally acquainted with Lee. An 1866 newspaper interview of ex-slave Wesley Norris recalled the “real character of the man.” Lee ordered him, his sister Mary and their cousin George Parks whipped fifty lashes each for their 1859 failed escape attempt. They were sent to Alabama before being sent to Richmond from where Norris escaped in 1863. Employed by the federal government at Arlington National Cemetery (Lee’s former estate), Norris offered to arrange for black and white witnesses to verify his statements; no doubt he was struck by the irony of again laboring in Lee’s symbolic shadow.

Lee never became reconciled to his defeat. The historical fact is the antebellum Lee supported slavery and the postwar Lee publicly reembraced white supremacy and recommended Blacks’ forced deportation to Africa. At an August 1868 meeting of twenty-seven ex-Confederate leaders at The Greenbrier resort, White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, he endorsed what became known as the White Sulphur Springs Manifesto that called for whites’ national reconciliation but opposed African American suffrage and political equality. Greenbrier welcomed Lee as an esteemed guest during his vacations, hosted annual Lee Monument Balls as fundraisers for his Richmond equestrian monument after his 1870 death, and observed Robert E. Lee Week well into the 1940s.[9]

Frederick Douglass, the nineteenth century’s most influential African American, shed no tears at his passing: “General Lee . . . is dead, and so is Benedict Arnold . . . . The one great fact of Lee’s life [is] namely, his treason.” Douglass criticized Lee statue proposals: “Monuments to the ‘lost cause’ will prove monuments of folly . . . of a wicked rebellion . . . It is a needless record of stupidity and wrong.” (Owing to the South’s postwar poverty, twenty years elapsed before the erection of Richmond’s Lee statue.) A generation later African American intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois, a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), castigated Lee as a fool and a traitor because “he led a bloody war to perpetuate human slavery . . . [and] helped maim and murder thousands in its defense.”[10]

Blacks in the Box?

In the year of the Lee Monument dedication, the 1890 federal census enumerated Blacks as comprising 38 percent of the state’s 1,655,980 population and 44 percent of “gainful occupations.” Richmond’s 32,555 Black residents comprised 40 percent of the city’s 81,388 inhabitants. They owned $968,736 in real estate ($27 million in 2022 dollars)—and were 30 percent of Black property ownership among sixteen major Virginia cities. But all did not bode well; between 1870 and 1892, three thousand Black males were disenfranchised after felony or larceny convictions in Richmond courts. In 1890, three Black men were lynched in the counties of Russell, Charlotte, and Mecklenburg; thirty-four Black males, six white males and one white female were lynched during the 1890s.[11]

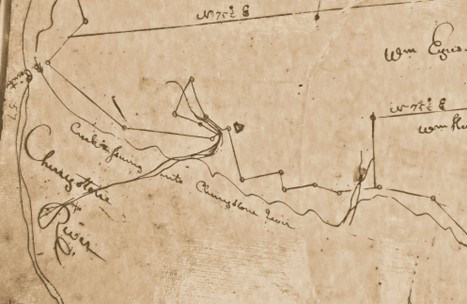

Of approximately one hundred items discovered in the monument’s copper cornerstone box in 2021, at least three are publications referencing Black Richmonders. Chronologically, the first is History and Reminiscences of the Monumental Church (1880). It contains fourteen mentions of “colored” and slavery/slaves and whites’ postwar forebodings of them as indigenous threats: “By the action of the Federal government, several millions of slaves have suddenly been set free, and left amongst us a potent power for good or evil, in connection with the destinies of this country.”[12]

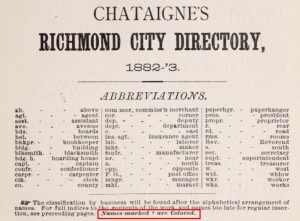

![Chataigne’s Directory of Richmond, Virginia asterisked entries for various Black Richmonders surnamed “Mitchell” including Rev. Henry H. Mitchell, first pastor, Fifth Street Baptist Church, organized 1880, in Richmond’s predominately black Jackson Ward [Source: https://www.fifthstreetbaptist.org/our-history], 1882-1883. Public Domain](https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Page-245-Mitchell-detail-217x300.jpg)

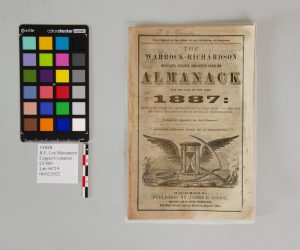

A third publication, The Warrock-Richardson Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina Almanack (1887), contains miscellaneous information and a monthly chronology of noteworthy events. Among these is the Emancipation Proclamation (January), Black members of the General Assembly (“Italics, colored”), and “Virginia Congressional Votes” by race (“White” and “Colored”). The almanac mentions Lee’s January 1807 birthday, of April as when the “Civil War begun 1861” and of the 1865 Appomattox surrender, and Lee’s October 1870 death.[14]

Unsurprisingly, items representative of Black civic, fraternal and business institutions such as John Mitchell’s Richmond Planet, William Washington Browne’s the Grand Fountain, United Order of True Reformers, the First African Baptist Church and similar exemplars were excluded. As far as whites were concerned, Black Richmonders were Unionist collaborators during the war, postwar “racial agitators” for Republican “radical political agendas,” and social inferiors.[15]

“Whose history? Who decides?”

The escalating war of words between neo-Confederates and descendants of the enslaved awaits an equitable closing chapter. In the postmodern reshaping of public memory, Lee and other Confederates, demoted and demythologized from the pantheon of American heroes, are increasingly regarded as anti-Black proslavery secessionists and unrepentant racist traitors seemingly shackled to the Lost Cause. Their modern-day apologists resent what they perceive as demonization of their cultural icons and ‘heritage’ (which incidentally includes racism).

Monuments matter. Is there a middle ground for recontextualization of history and memory in a pluralistic society? In an essay commemorating the 400th anniversary of the first enslaved African arrival in Virginia, I posed three questions: “How much history is too much? Whose history? Who decides?”[16] These remain emotively relevant across the Old Dominion’s history—and perhaps always will.

–Professor Ervin L. Jordan Jr.

Research Archivist

Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library,

University of Virginia

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR’s archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

[1]Monument Association, Official Souvenir of the Dedication of the Monument to General Robert E. Lee: Containing a Full and Lee Monument Association, Complete History of the Monument Association, Together With the Order of Exercises and Other Matter (Richmond: R. Newton Moon & Co., 1890); Anne McCrery, Errol Somay & Dictionary of Virginia Biography, “John Mitchell (July 11, 1863-December 3, 1929),” Encyclopedia Virginia, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/mitchell-john-jr-1863-1929/; Richmond Planet articles: “The Lee Monument Unveiling: Thousands Present—Confederate Flags Everywhere Displayed,” May 31, 1890 (“Rebel flags,” “The South may revere,”), p. 1, col. 2, and, untitled articles, June 7, 1890, p. 2, cols. 2 & 3 (“an old colored man,” “The Negro”); Ann Field Alexander, Race Man: The Rise and Fall of the “Fighting Editor,” John Mitchell Jr. (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2002), 36-37 (Planet’s influence), 39, 74, 208, 220n36, 248n8; Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1997), 148, 151-54 (“an old colored man”), 245n64-67, 246n71; Virginia Writers’ Project, The Negro in Virginia (New York: Hastings House, 1940; reprint, Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair, 1994), 314 (Planet’s circulation); https://www.wric.com/news/local-news/richmond/unanimous-vote-richmond-confederate-monuments-going-to-black-history-museum/.

[2]Richmond Planet articles: “The Lee Monument Unveiling: Thousands Present—Confederate Flags Everywhere Displayed, May 31, 1890 (“from New York”), p. 1, col. 2; “A Gala Day: The Parade A Success,” October 18, 1890, p. 1, cols. 1-2 (“We are American citizens”) and p. 4, col. 5 (“They say”); “Thanks,” October 25, 1890, p. 1, col 2 (Mitchell’s parade staff); Rev. William J. Simmons, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising, With an introductory sketch of the author by Rev. Henry M. Turner (Cleveland, Ohio: G. M. Rewell & Co., 1887), 314-20 (Mitchell), 754-56 (Price); Alexander, Race Man, 39; Savage, Standing Soldiers, 151-154; Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego & Dictionary of Virginia Biography, “John Mercer Langston (1829–1897),” Encyclopedia Virginia, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/langston-john-mercer-1829-1897); Rayford W. Logan and Michael R. Winston, Dictionary of Negro Biography (New York: W. W. Norton, 1982), 503-504 (Price).

[3][C. A. Taylor, Traffic Manager, R., F. & P. R. R. Co.], Colored People’s Celebration at Richmond, Va., October 15th, 16th, and 17th . . . to establish a National Thanksgiving Day for Freedom, to be annually observed by the Negro Race. . . . Speakers from all over the country (Richmond, Va., 1890), Library of Virginia, Richmond; “The Governor Refused: The Committee’s Explanation in Re-Request for the Howitzers to Fire,” Richmond Planet, October 18, 1890, p. 4, col. 3 (“Citizens of African descent,” “commemorative of our emancipation,” “it has not been the custom,” “to fire any salutes for them”).

[4]“Notice!: The coloured people of the city of Richmond would most respectfully inform the public, that they do not intend to celebrate the failure of the Southern Confederacy, as it has been stated in the papers of this city, but simply as the day on which God was pleased to liberate their long-oppressed race/C. Harris, J. Cocks, J. Edmunds, F.J. Smith, N. Williams, Committee,” “Broadside, from the Committee, 2 April 1866,” Virginia Museum of History & Culture, Richmond, Virginia, https://virginiahistory.org/broadside-committee-2-april-1866; Ervin L. Jordan Jr., “‘Traitors shall not dictate to us’: Afro-Virginians and the Unfinished Emancipation of 1865” in William C. Davis and James I. Robertson Jr., eds., Virginia at War, 1865 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012), 121 (“Colored League”).

[5]Edward A. Pollard, The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates. Comprising a Full and Authentic Account of the Rise and Progress of the Late Southern Confederacy--the Campaigns, Battles, Incidents, and Adventures of the Most Gigantic Struggle of the World’s History, Drawn from official sources, and approved by the most distinguished Confederates, With Numerous Steel Portraits (New York: E. B. Treat & Co., Publishers, 1866), 50 (“noble type of civilization”), 750, 752; Edward A. Pollard, The Lost Cause Regained (New York: G. W. Carleton & Co., London: S. Low, Son & Co., 1868); Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, 2 vols. (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1881), 2: 764 (“Esto perpetua”); Jefferson Davis, Beauvoir, Harrison County, Mississippi, to Rev. F. Stringfellow, June 4, 1878 (photostat), Jefferson Davis Letters to Frank Stringfellow (“the failure”), Accession 5162, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

[6]Margaret E. Wagner, Gary W. Gallagher, and Paul Finkelman, eds., The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference, with a foreword by James M. McPherson (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002), 743 (“idealization of a society”), 805 (“nostalgia for Southern gallantry and the prewar status quo”); Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991), 217 (“cult of the dead”); David Ulbrich, “Lost Cause,” in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, David Heidler and Jeanne Heidler, eds. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 1222 (“white Southerners”).

[7]Southern Poverty Law Center, “Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy (3rd Edition),” February 1, 2022, https://www.splcenter.org/20220201/whose-heritage-public-symbols-confederacy-third-edition]; Seth C. Bruggeman, “Memorials and Monuments,” The Inclusive Historian’s Handbook, July 18, 2019, https://inclusivehistorian.com/memorials-and-monuments/; Anna Ivanov, Karyn Pugliese, Lucy Yip and Meesh Zucker, “Monumental Memory in Space,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, https://lyip12.github.io/memorial/.

[8]Tony Horwitz, Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1998), 152, 171-172; Ervin L. Jordan Jr., Charlottesville and the University of Virginia in the Civil War, second edition, The Virginia Battles and Leaders Series (Lynchburg: H. E. Howard, Inc., 1988), 109 (“Fate”).

[9]Ervin L. Jordan Jr., “Monument Man: Robert E. Lee: America’s Most Honored Traitor,” symposium “Lightning Rods for Controversy: Civil War Monuments Past, Present & Future,” Library of Virginia, February 25, 2017, https://www.c-span.org/video/?423748-101/controversy-general-robert-e-lee-monuments (“As America’s most honored traitor”); Wesley Norris interview, “Robert E. Lee—His Brutality to His Slaves,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, April 14, 1866, p. 4, col. 4; John W. Blassingame, Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977), 467-68 (Norris interview); Ervin L. Jordan Jr., Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 1995), 258-59, 324-25 (Custis slaves); Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading The Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters (New York: Viking, 2007), 144-46, 149-151, 154, 266, 286, 431, 451-54, 456 (Lee’s racism); Alan T. Nolan, Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 139, 141-150; Robert S. Conte, The History of The Greenbrier: America’s Resort (Charleston, West Virginia: Published for the Greenbrier by Pictorial Histories Pub. Co., 1998; ninth printing, 2014), 66-73, 67-68, 84-85, 118-119.

[10]Frederick Douglass, “Monuments to Folly,” The New National Era (Washington, D. C.), December 1, 1870, p. 3, col. 2; [W. E. B. Du Bois], “Robert E. Lee,” The Crisis, vol. 1, no. 3 (March 1928): 97 (“he led a bloody war”).

[11]Table 1, p. 1, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/bulletins/demographic/51-population-va.pdf; Virginia Writers’ Project, The Negro in Virginia, 338-339 (1890 Virginia; “gainful occupations”); Alrutheus Ambush Taylor, The Negro in the Reconstruction of Virginia (Washington, D. C.: The Association For The Study of Negro Life and History, 1926), 135 (real estate); Alexander, Race Man, 79 (1890 Richmond); Richmond Hustings Court, Official List of Colored Persons Convicted of Felony or Petit Larceny in the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond and Thereby Disfranchised, From 1870, to October 1892 (Richmond, 1892), 3-13; Richmond Police Court, Official List of Colored Persons Convicted of Petit Larceny in the Police Court of the City of Richmond and Thereby Disfranchised, From April 2d, 1877, to January 12th, 1892 (Richmond, 1892), 3-14; Gianluca De Fazio, Department of Justice Studies, James Madison University, “Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia,” https://sites.lib.jmu.edu/valynchings/view-by-decade/.

[12]“Corner-stone Contributions: “Unboxing the Lee Monument,” January 12, 2022, updated January 13, 2022, https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/news/corner-stone-contributions-unboxing-the-lee-monument/ and “Contents of Richmond Robert E. Lee Monument Copper Cornerstone Box”: https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Contents-of-the-Richmond-Robert-E-Lee-Monument-Copper-Cornerstone-Box.pdf; George D. Fisher, History and Reminiscences of the Monumental Church, Richmond, From 1814 to 1878 (Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson, 1880): 3-4, 121, 133-34, 209, 259 (12 references “colored”); 234 (2 references “slave/slaves”); 311 (“By the action of the Federal”); Jordan, “‘Traitors shall not dictate to us,’” 119-120.

[13]J. H. Chataigne, Chataigne's Directory of Richmond, Va., to Which is Added a Street and Number Directory, Giving Names of Occupants After the Numbers; A List of the Post Offices of the State Of Virginia and Appendix Pertaining to State and City Governments (Richmond: J. H. Chataigne, compiler and publisher, 1885), 67-68 (Black Richmond city councilmen), 83 (“Colored Churches”), 96 (“Colored Persons’ Burying Ground”), 101 (“Names marked”), 313 (John Mitchell Jr., editor), 342 and 492 (Richmond Planet and Planet Publishing Company).

[14]David Richardson, John Warrock, R. K. Bowles, The Warrock-Richardson Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina Almanack (Richmond: Published by James E. Goode, 1887), mentions of General Robert E. Lee: p. 9 (January 1807 birth), p. 12 (April 1861 “Civil War begun 1861”), p. 12 (April 1865 Appomattox surrender), p. 18 (Lee’s October 1870 death); Black-related events: p. 9 (January 1865 Emancipation Proclamation), 26-27 (Black members of the General Assembly), 30-35 “Virginia Congressional Votes” (“White” and “Colored”).

[15]Alexander, Race Man, 34-38, James D. Watkinson, “William Washington Browne and the True Reformers of Richmond, Virginia,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography vol. 97, no. 2 (July 1989) 375-98, see also Michael B. Chesson, Richmond After the War, 1865-1890 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1981); Ervin L. Jordan Jr., “Lies & Legacies: Cultural Spaces, Public Places, Reparations,” Albemarle-Charlottesville NAACP Branch Annual Freedom Fund Banquet, September 16, 2016 (“racial agitators,” “radical political agendas”).

[16]Ervin L. Jordan Jr., “Jamestown Shuffle: Foundations of American Racism and Slavery in Virginia, 1619-1830,” in William H. Alexander, Cassandra Newby-Alexander and Charles Ford, eds., Voices from within the Veil: African Americans and the Experience of Democracy (Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008), 46-67 (“How much history”).