Alice Boucher of Colonial Virginia’s Eastern Shore

While researching the site of a former plantation in Northampton County, our intrepid archaeologist takes a detour down the rabbit hole of centuries-old court records, where he unearths the story of a tenacious 17th-century widow.

By Michael Clem | DHR Archaeologist for Virginia’s Eastern Region

I first came across the name Alice Boucher while searching through the Accomack County court order books from the 17th century. I was looking for anything related to Colonel William Kendall, the owner of Eyreville, the site of a 17th-century plantation in Northampton County where I have been excavating and documenting for some time. I was reading a passage about a court case involving Kendall when I scanned further down the page, past what seemed relevant. Often in these court order books, the story may not be fully linear. It can appear to end but pick up again after a brief unrelated item. In this instance, Kendall’s story ended but the one that followed was so compelling that I had to continue reading.

Alice’s name appears a total of seven times in the court records that I found. Her earliest appearance was in August of 1663. Her husband William Boucher appeared in 1655 in Northampton County as a witness and then again in Accomack in October of 1658. This latter entry was in reference to an eight-year lease agreement for 100 acres with George Hack, a physician, at a place called Hack’s Neck. In the agreement, William was required to plant 50 apple trees. William also shows up in a deposition in November 1663 about a dispute over a pig between two neighbors (pig disputes make up an inordinate number of court proceedings). The record of William Boucher’s statement reads, “This sow and others use Mr. Hack’s swamp near the branch by Boucher’s house.” William largely disappears from the records after this time. His fate is unclear. What is certain is that at some point before 1671, he passed away. He was born around 1615, and Alice was born about 1631. I only include these accounts of Alice’s husband to add some context for what follows. The records include various spellings of the last name as Boucher, Bouchier, Boutcher, and, on a few occasions, as Butcher.

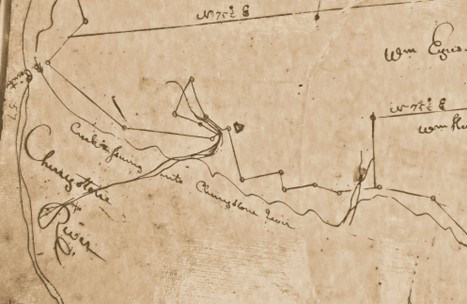

In August of 1663, Alice, along with Elizabeth Leverit and Robert Brace/y, were brought before the court. The charge was that the three had argued and fought on “ye Sabbath day”. All three were sentenced to be ducked and to pay court costs. The passage from the Court Order abstract reads:

Whereas Robert Brace having a woman servant named Elizabeth Leverit incorrigible and impudent, which said servant upon ye said Brace complaint ye preceding Court, was punished for insolent demeanor towards her master, and since ye Issue ye said woman servant, Alice Boucher and Robert Brace, have lawlessly scolded, fought, and misdemeaned themselves on ye Sabbath day the Court have therefore ordered the ye said Elizabeth Leveret & Alice Boucher be ducked, and for that ye said Brace hath degenerated so much from a man, as neither to bear Rule over his woman Servant nor govern his house, but made one in that scolding society, wherefore ye said Brace is censured to be ducked with his woman servant & Alice Boucher, and pay Court charges.

Ordered that Alice Boucher be committed to the sheriff’s custody and be ducked for fighting and scolding, and also to pay court costs. (Accomack County Court Orders Vol. 2, p. 26a)

Later, Brace/y paid a fine and was allowed to escape the humiliation of public ducking. Both Alice and Elizabeth, presumably not having the means, or perhaps the court did not allow any leniency for the two women, were required to withstand their punishment. Ducking is, of course, the practice of tying a person to a chair that is attached to beams by which it would be lowered into a body of water. A description of the process:

Most self-respecting settlements also had a ducking stool, a seat set at the end of two beams twelve or fifteen feet long that could be swung out from the bank of a pond or river. This engine of punishment was especially assigned to scolds—usually women but sometimes men—and sometimes to quarrelsome married couples tied back to back. Other candidates were slanderers, "makebayts," brawlers, "chyderers," railers, and "women of light carriage," as well as brewers of bad beer, bakers of bad bread, and unruly paupers. In the absence of a proper ducking stool, authorities in some climes, as in Northampton County, Virginia, ordered the offender "dragged at a boat's Starn in ye River from ye shoare and thence unto the shoare again." (James Cox, Colonial Williamsburg)

Just three months later, Alice Boucher next appears in court on November 10, 1663, the day before her husband William gave his testimony about the pig. This time, she was charged with using “scandalous words against the court.” She confessed and asked for the court’s favor with a promise to “behave better.” She was acquitted and had to pay court costs. The court deposed a woman named Joane Brookes on the same day. Her testimony gives us some further insight into the case:

She (Brookes) was at William Wotton’s house last Monday along with Alice, the wife of William Boutcher. Alice said she was pregnant with a child as big as her fist when Capt. Parker (Sheriff) caused her to be ducked. She miscarried and said she would be revenged on him within a year. Joane told her she should do it soon and not keep it in her breast so long. Alice said, “He kept malice in his breast three years, for which I was ducked.” Alice wanted to have it tried in another place. Signed Jone (O) Brookes. (Accomack County Court Orders Vol. 2. p. 38a)

Several questions arise from this statement. First, who was Joane Brooks? Was she a friend? Was she an indentured servant in Wotton’s house? Alice evidently trusted her enough to tell her about something so personal. Joane Brookes doesn’t seem to appear elsewhere in the records. There is mention of a “Mrs. Brookes” in an unrelated instance some years later, but it is unclear if it is the same individual. Who was Wotton? Was he a neighbor of Alice and William Boucher? Was Alice there on a social visit or some other business? Did the case come to the court’s attention because of Brookes or Wotton? How did the story get into the ears of the court? Finally, what was the malice that Captain Parker held for Alice? Did one or the other commit a transgression three years before? The records I found at this point don’t provide any answers. It’s clear the relationship between Alice and Captain Parker were strained enough that the former had wished for a trial in another jurisdiction, either to attempt to protect her reputation in her community or she felt she would not be tried fairly.

Alice next appears in the books some eight years later, on July 19, 1671. The court ordered the sheriff to take Alice and her two daughters, Dorothy and Francis, into custody. They, along with John Browne, were examined by Southy Littleton. Littleton was a prominent citizen and served on the court. The testimony from this date is difficult to summarize, so I will just let it speak for itself:

July 19, 1671

A jury inquired and examined Alice Boucher and her two daughters about a child delivered in private to Alice. Ordered that the sheriff take Alice and her two daughters into custody till they gave a bond for good behavior and paid court costs.

Examination of John Browne aged about 25 years: On Monday, the third of July, the widow Alice Boucher requested him to help her reap, which he did. As it was late, he was forced to stay all night; about midnight Alice Boucher called to him and said she had dreamed that some of the neighbors had raised a scandal, saying that she and Browne had lain together. She asked Brown to leave the house immediately, but he refused. The two daughters took light wood into the loft where they kept a “great light” all night, whispering and twice coming down to see if Browne were asleep. He lay still and pretended to sleep. About an hour before day he heard them fetch scissors. Looking up into the loft through wide spaced boards, Browne saw the two daughters holding Alice; from that place in the loft, at least a quart of blood fell down on a chest. Browne saw that Alice’s legs were bloody with something hanging down from her body. She immediately sent to see if Browne was asleep, which he feigned. The two daughters went out, one with a shovel and hoe, the other with something “wrapped up in her lap”. Browne followed at a distance and saw them bury in the corner of the cornfield fence what the last girl had been carrying. When they went up to their mother again it was daybreak. When Alice came down, her legs were bloody, and wherever she stood, she immediately bloodied the place. Several times she complained of pain in her belly and asked Browne if he knew of anything “good for the plague of the guts” or if he thought Tobias Selvey could do her any good. Signed 6 July 1671, by John (X) Browne before Sowthy Littleton.

Because Alice Boucher, widow, about 3 July had a child which she concealed, privately buried and denied, it was ordered that Thomas Leatherberry, constable, take Alice to the house of Mr. Thomas Fowlkes and give her to the sheriff, where she was to stay till the court made further decision. Signed 19 July 1671, by Sowthy Littleton.

Examination of Alice Boucher aged about 40 years: On 4 July, about an hour before day, Alice delivered a son; she did not know if he was born alive or dead, having no one with her but her two daughters. She cut and tied the “naval string” herself. As soon as she could, she went to dress the child, but found it to be dead; she ordered her two daughters to bury it. Alice declared that the child was alive immediately before it was born.

Examination of Dorothy Bouchier aged about 14 years: On 4 July, to the best of her knowledge, her mother was delivered of a stillborn son. Her mother asked Dorothy and her sister to bury the child, which they did about eight or nine o’clock on the same morning.

Examination of Francis Bouchier aged about 13 years: She declared the same as her sister. All three were questioned before Southy Littleton and recorded by John Culpeper 2 August 1671. (Accomack County Court Orders p. 8, 9)

The jury considered the case of Alice Bouchier and her daughters. They determined that the child was lost for the want of help.

(Accomack County Court Orders Vol 3. p. 9)

Alice only appears three more times after this, while her daughters appear once more. Browne never appears in the court order books again.

In August of 1671, a mere month later, Alice was required to pay a debt of 450 pounds of tobacco to John Terry along with the cost of the lawsuit (Accomack County Court Orders, Vol 3. p.13). It is not clear from the records what this debt was for. This gives the impression that the debt was paid without issue. Tobacco was the primary currency in the colony during that time, and most debts were measured out in pounds. The amount of tobacco Alice paid was not great but also not insubstantial. Tobacco’s value constantly fluctuated due to crop failure, demand, shipping costs, and other variables, making it difficult for us to accurately place its value during the time of Alice’s payment. However, there are records from the same time showing 100 acres selling for 2300 pounds. In just five such payments, Alice could have possessed her own farm—if she didn’t already. John Terry is nowhere to be found in the records following this exchange. Could Terry have been the owner of John Browne’s indenture? Was it possible that Terry rented Browne’s labor to assist the widowed Alice with her farmwork? It’s also possible that this was simply a payment to Terry for some goods.

On December 19, 1671, the sheriff was ordered to summon seven women, including Alice, to court to answer to the charge of fornication. In the 17th century it was not unusual for the court to regularly summon multiple women for this charge. The punishment was either public whipping or a fine of 500 pounds of tobacco. In many of these cases, a “gentleman” would step forward and pay the fine. It appears to be, in some ways, an easy means of collecting tax for sex. In the case of Alice, her old friend from her first court appearance, Robert Brace/y, paid the fine for her. It is unclear what the social or financial impacts of such charges were for “free” women. Indentured women, however, often had their fine paid by their master, which typically resulted in an additional two years being added to their (typical seven-year) original indenture agreement. If a child was born out of the indentured woman’s “crime,” an additional year was added for the “hindrance and loss of time during pregnancy and delivery.” The child would also be subjected to an indenture until the age of approximately 24 years to make up for the cost of housing, clothing, and food.

The final entry that I found in the books for Alice Boucher is from May 1672. She was about 40 years old. It was recorded that Alice divided a number of cattle amongst her children. Dorothy, listed as her oldest child, was given three cattle, as was Francis; Robert and Martha were given two each; and Anne was given one. That were eleven cattle in all. Did Alice have more? There were no other details about this substantial gift, and one wonders: what was the point? Was Alice concerned that her children needed to be provided for? Her oldest children were about 14 and 15 years old. The ages of the others were not listed in the records. Was Alice ill and preparing for death? Was she about to remarry and wanted her children to hold some form of financial security? Researchers familiar with these records contend that it was common in the 17th century for a woman, before remarrying, to give her valuables to her children from a previous marriage to ensure that the new husband would not gain ownership of treasured possessions.

The records are silent about Alice from this point onward. I found no indication that Alice and her family moved after her late husband William Boucher signed the eight-year agreement with Dr. Hack in 1658. There is no lease agreement elsewhere recorded with the court. I suspect that, as a widow who seemed to be prospering, Alice had reached an agreement with Hack to stay in place—at least until 1672, the year of her final appearance in the court order books.

In the end, we are left with a mystery. A brief encounter with the life of Alice Boucher. We find her in her early 30s and lose her again after about 11 years. It is possible that further searches for records in other jurisdictions may reveal more clues about the fate of Alice. Perhaps we may find the record of her birth. Maybe her death was recorded in a church elsewhere in the colonies. For now, this is all we have. I did not find a record indicating that she remarried after the death of William, though it’s possible she moved out of Virginia and remarried elsewhere.

We can only imagine the life that Alice led. While the difficulties displayed in the records speak about the hardships of being a woman in colonial Virginia, there are still likely many burdens that we will never know. Raising five children as a widow must have been difficult when her labor comprised her sole income. A bad crop of tobacco or a decline in produce in the garden could easily have made life much more difficult for Alice and her family. Yet, somehow, Alice made it to a point where she could pay a sizeable debt, and then shortly thereafter, give each of her children a substantial gift. I’d like to think of Alice as the kind of strong woman who decided to take on the challenges at any cost and succeeded, even though she had little choice in the matter.

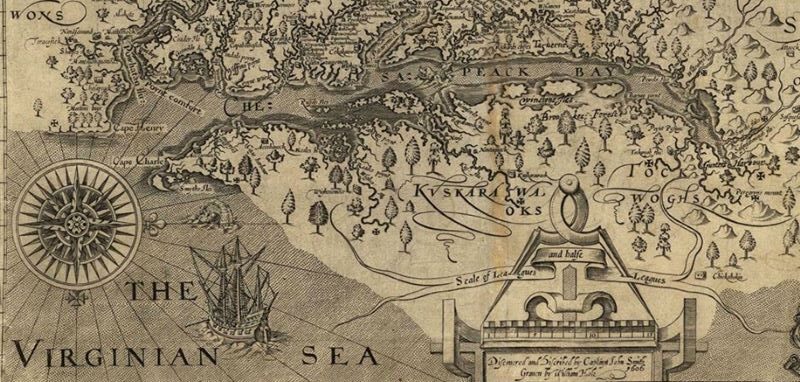

After studying Alice’s life, I began a search for the possible location of her home. I attempted to find the oldest map of the area that features the area of Hack’s Neck, and I had to rely on relatively recent 20th-century United States Geological Survey (USGS) topographic maps as well as old nautical charts. I studied these sources and found an area that fits the description given by William Boucher in his testimony about the pig. The area, consisting of mostly swamp, is located by a branch (creek) where William had said his house stood. We know from the initial lease that the property was 100 acres, and that William was required to plant 50 apple trees. On the maps, I followed various indicators of property boundaries, such as tree lines and ditches. I also looked for swampland along a creek. I then checked DHR’s site records and found an entry for a site that is on the edge of a parcel containing a 100-acre field. According to DHR’s records, this site dates to approximately the third quarter of the 17th century, based on the artifacts recovered there. The site was recorded by a passerby traveling on a boat. They had found artifacts eroding from the shoreline of a creek that bears a version of Alice’s name.

After conducting some research into tax records, I found the owner of the property. A retiree who lives outside of Virginia, he told me that he visits the property from time to time. I mentioned the story of Alice to him and described the site’s location. He responded, “Oh, you mean up where the old crabapple trees are growing?” Old apple orchards left to re-seed on their own will, over time, revert to yielding smaller apples that have little resemblance to the original parent variety. Have we found the location of Alice’s home, where William planted 50 apple trees and where her infant son was laid to rest more than 350 years ago? Where she and her children worked so hard to survive?

Swampy conditions exacerbated by inclement weather waylaid several planned trips to examine the site this winter. As warmer months approach, joined by a bit of luck—and possibly a kayak—I’m hopeful we’ll get there.