After Dam Removal, Archaeology at Jordan’s Point, Maury River, Lexington

Revelations of an Early Industrial Landscape

The Maury River is neither deep nor wide where it rolls past Jordan’s Point. Only a couple hundred yards south, and up a steep wooded slope, cadets at Virginia Military Institute busily stride between the pale-olive buildings of the post. To the east, lazy traffic buzzes over the Route (US) 11 bridge and into downtown Lexington. Federal-style red brick shops and houses line the town’s streets, none of them level. The largest expanse of even ground in Lexington—outside of the football stadiums of Washington & Lee and VMI—is along the river at a place once clanking and bustling with mills. Jordan’s Point was the industrial and commercial center for Lexington for most of its early life.

Early History

In October of 1777 the General Assembly carved about 600-square miles from Botetourt and Augusta counties to form the new county of Rockbridge, named for a geologic oddity then owned by Thomas Jefferson, Natural Bridge. Almost concurrently, Lexington was established as the county seat, its name commemorating a Revolutionary War battle. As curtains closed on the 18th century a new nation formed and industry sprang up throughout the furrowed countryside surrounding Lexington.

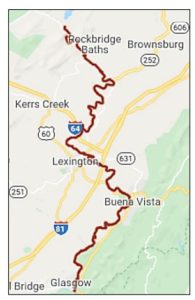

The Maury River, known as the North River until 1945, penetrated Rockbridge’s diamond shape from south to north. Farmers, colliers, ironmongers, millers, and timber men were well connected by overland routes up and down the Shenandoah Valley, but the North River offered a route east through the Blue Ridge Mountains and to the Port of Richmond. From there, pigs of iron were melted in foundries along the Kanawha Canal and in Petersburg to be cast and beaten into railroad rails, locomotives, and ordnance. Grain and other Rockbridge region goods were shipped to Richmond, as well, for domestic and export trade.

By the middle of the 19th century a newly incorporated Lexington was home to a state arsenal and two colleges. In 1850 the North River Navigation Company set to building locks, clearing river obstructions, and digging canals around dams and other obstructions up the North River from its confluence with the James at Glasgow. Packet boats from Richmond could then service Lexington, a 46-hour trip. Immediately following the Civil War, Lexington benefitted from post-war investment to rebuild industry destroyed by the war and build new infrastructure. Lexington’s first rail service closely followed the war and came up the Valley (southward) from Staunton to connect the city to the Virginia Central line. Each of these arterial tendrils—first, the Great Road (roughly today’s US 11); second, the canals; finally, the railroad—had one thing in common. They all crossed the North River at Jordan’s Point.

Hydraulic Power and Dams Spur Industry

In 1806, a grist mill and sawmill were built on a point of land between the North River and Woods Creek. John Moorhead and John Jordan partnered to raise the capital to construct a dam across the river and put the sawmill and grist mill into operation. A rapidly growing Lexington required thousands of board feet of lumber and provided a convenient nexus for grain milling. John Jordan formed a second partnership with the Darst family, who owned a pottery and brick kiln in Lexington. Between Jordan, Benjamin and Samuel Darst, and John Chandler, one of the region’s largest construction firms was established. By 1810 the construction firm had built portions of Washington College (now Washington & Lee), Anne Smith Academy, and the industrial center at Jordan’s Point.

Harnessing stream and river power for milling was not new during the early 1800s. Indeed, the concept of water power goes back many centuries. However, the early 19th century was different. Steam power was in its infancy yet the need for mechanical power increased exponentially throughout the young Republic, especially where tumbling streams and high-velocity rivers could turn valley grains into export flour. Indeed, by 1816 a large cotton factory was built at Jordan’s Point and operated entirely off water power.

To mill with hydraulic power means to control a flowing water source. Diverting a river or creek into a small ditch, called a headrace, allows energy to be compounded and focused. A current of water bulleting down a headrace can be directed over a mill wheel (overshot), across the bottom of a mill wheel (undershot), or through a turbine. Mill wheels and turbines can be extraordinarily efficient, capturing up to 90 percent of ambient energy. Through gearing, often made of wood, the power of a millwheel could be imparted to a rising and falling sash sawmill to cut logs, to a run of millstones to grind grain, to a trip hammer to pound iron, or any number of mechanical devices. This infrastructure was costly, and usually required a great capital investment often undertaken through partnership. Keeping it running was the only way to make money and pay off construction and operating costs. Running machinery needed lots of running water, lots of it.

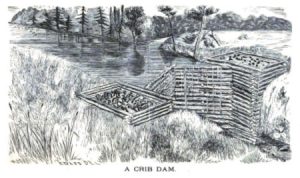

Early American dams were most often made from stone, the most common of which were called “crib dams.” A set of timber boxes, laid like a set of connected log cabins, was set into a waterway. Vertical pinning and giant sill logs formed a heavy base and as each course of timbers was laid rocks from the streambed were used as rubble infill. On the upstream side, many crib dams use plank armor to divert extraordinary hydraulic pressures of floods up and over the dam (see the plank crib dam illustration below). We often think of dams now as having dry tops but many early dams utilized a notch to maintain constant pool depth or a dissipated spillway across the top of the dam. Crib dams were an efficient and cheap method of impounding water, raising the level of a river to create stored energy for mills. The more water stored, the longer a mill could run and avoid shutdowns during periods of low water. Crib dams also were the least resilient to floods and the most prone to washout.

The Dam at Jordan’s Point

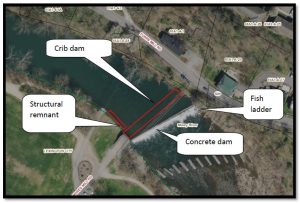

The dam at Jordan’s Point was replaced or substantially repaired during the first half of the 19th century and by 1840 was considered stout enough serve as a footer for a double lane covered bridge. In 1850, land at Jordan’s Point was bought by the North River Navigation Company as a strategic asset for their canal connecting the upper North River to the James River at Glasgow. A short section of canal bypassed the crib dam, threaded through the mill complex, and included a gauge lock used for measuring cargoes and assessing tolls for boats passing through. Just below the dam was a wharf area for loading and unloading cargo, the Port of Lexington.

Not long after the canal was established through Jordan’s Point a rail trestle was constructed perpendicular to the canal and over the river, one of the few cases where the rail line didn’t supersede the canal by laying tracks directly on the towpath. During the 1880s Breechenbrook’s Foundry and Machine Works was built up the hill from the canal and on the rail line, perhaps leveraging the intermodal nature of Jordan’s Point.

In 1911, a large concrete dam was built to replace the crib dam and provide water power to the Lexington Roller Mills. It was much higher than the earlier crib dams and more likely to survive floods. The cotton factory and sawmill were by then a distant and unpleasant memory, having been burned by Gen. David Hunter during his 1864 campaign to deprive the Confederacy of industrial centers. The Lexington Roller Mills not only produced flour but sorted bran, ground corn meal, made animal feed, and even operated its own cooperage to produce barrels.

The 1920s were particularly hard on the river and its infrastructure. Floods in 1926 and 1927 caused sufficient damage to the mill that its owners, the Moses family, ceased operations and abandoned the concept of rebuilding. If those floods weren’t enough, a flood of more than four times the magnitude of the 1920s flooding swept the North River in March of 1936. By then, the river was abandoned to industry in Lexington. During the 1945 General Assembly, legislation renamed the North River for Matthew Fontaine Maury. Maury had been a noted professor at VMI and, prior to the Civil War, Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Observatory. At about the same time the river changed names, Jordan’s Point was purchased by VMI, which then transferred it to the City of Lexington where it is now a public space and interpreted historical landscape.

Removal of the Dam and What It Revealed

In 2019, the failing concrete dam at Jordan’s Point had become an unsafe blight on the Maury River. Public outcry to save the dam was outweighed by the cost to rebuild and restore as well as a push to reopen the river to fish, who seek out the cool, oxygenated waters that spill out of Goshen Pass. And so, the dam came down. Footers for the railroad bridge were removed and a large, tracked excavator chewed a hole in the concrete edifice to release the Maury back to a state of nature. As waters poured through, released from captivity, history was unveiled. For the first time in two centuries the various wood and stone dams were exposed. Giant pine, chestnut, oak, maple, gum, and locust timbers, preserved by the cold water, lay silently embedded in the river’s rocky bottom. Preservation attempts were made to salvage some of the crib logs and they were tagged and removed to a storage yard. Two millstones were also recovered; one may now be seen in front of the nearby Miller’s House.

But even once the dam removal project was completed, the historic unveiling had just begun. The Maury River, free to flow as it wished, began to scour away at thousands of tons of gravel, rocks, and silt that had come to rest behind two centuries of dams. Slowly, more and more was revealed. In July of 2020, I received a call from a local gentleman who kindly informed us of his discoveries. Upon visiting the site, our team from DHR found an incredible, once-drowned landscape of early American industry. From the concrete dam remnants to the crib dams, from mortise-and-tenon joinery of the old bridge footers to a small wrecked wooden ferry, the underwater history of Jordan’s Point was laid before us.

During three site visits we recorded everything we could see. Even upstream near the entrance to the headrace timbers in the riverbed revealed the footers for the early diversion dam. These, and some of the lower crib dam timbers likely date to the 1806 construction undertaken by Jordan and Moorhead. Rare is the opportunity to see such an intact landscape, even when most of the historic buildings are gone. That is the beauty of archaeology, it allows us to reconstruct and reinvestigate the past through material culture concealed in soil or sunken in our rivers, lakes, and oceans.

A little wooden ferry (its remnants shown in the photos above), carefully crafted of quality pine, once served the hamlets of Rockbridge by transporting horses, people, livestock, anything, from one side to the other. It may seem mundane but like a power outage, remove the simple things from everyday life and suddenly we clamor for their return. The loss of the boat likely caused a hardship for its owner and the community. Toll collectors and ferry operators were a part of rural Virginia life in the 1800s and watercraft like these were their tools.

And so the timbers, the ferry, the story remain. Their uppermost parts ripple the surface of the Maury as testament to the history.

Underwater Artifacts & Our Shared History

Why not remove it all to a museum?

It’s a common and frustrating question. Conserving large, complex, wooden items from a wet environment requires a huge space, lots of labor, expensive processes to slowly conserve the wood, and finally a place to interpret the remains for … ever. It’s a commitment to stewardship and cost that can only carefully and selectively be made. The most common, and sensible, alternative is to record these resources in place and share the results.

Historic artifacts in Virginia’s waterways are held in public trust. They are nonrenewable resources that are protected. If you find an artifact in the water, enjoy the experience through memory. Learn about the place, the people, the story and share that but please leave the artifact in place. Our shared history cannot be so if it is removed, imagine a river without artifacts – cleaned, so to speak. How sterile and uninteresting that would be. Instead, we study in place and sometimes scientifically study artifacts through careful removal and conservation. The story of Jordan’s Point is one worthy of study and it is best left in place as an intact outdoor laboratory. Enjoy the park, the natural setting, and the unique history of Lexington and its river.

To learn more, visit the web links below to read about Jordan’s Point including the 2016 nomination for listing the Jordan’s Point Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places. For questions about underwater archaeology in Virginia, contact me at Brendan.burke@dhr.virginia.gov or 804-482-8088.

–Brendan Burke

Underwater Archaeologist

State Archaeology Division, DHR

I would like to thank the following people for providing historical background on Jordan’s Point: Maral Kalbian and Dan Pezzoni for their 2019 report on the dam removal project; DHR staff for preparing the National Register Nomination; the Miller’s House Museum Foundation; and Bobby Jones for his consideration of the public historic resource.

Read the nomination form for more information on Jordan’s Point Historic District.

Click here to See historic photographs of the Jordan’s Point area: https://www.millershousemuseum.org/local-history-pictures