Cemetery Excavations in Charles City County Yield Surprising Discovery

In early spring, a cemetery delineation was conducted on a parcel of privately owned historic land in Charles City County. While no new graves were recovered from the delineation, the procedure allowed archaeologists to excavate the site. What they found could go on to reveal much more about the history of the property and the surrounding community.

By Michael Clem | DHR Eastern Regional Archaeologist

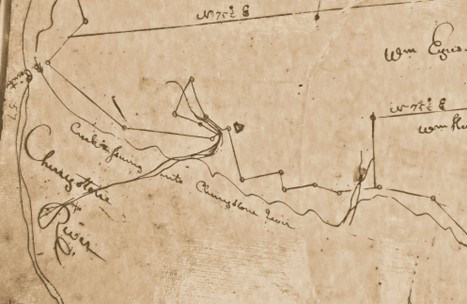

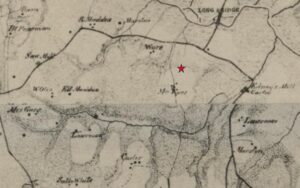

In March 2024, DHR Eastern Regional Archaeologist Mike Clem and two volunteers conducted excavations at a site in Charles City County located near the area known as Roxbury, a community close to the Chickahominy River that was named for a nearby plantation in New Kent County. Roxbury itself consists of just a couple of houses and is noted for having had a colonial-era tavern and, later, the only train station in the county. The site was initially discovered during the delineation of a cemetery on the same landform. The owner of the parcel was planning a new driveway to access the property and wanted to be certain that they would not impact any graves in that process. Cemetery delineation consists of mechanically stripping the topsoil to expose the top of possible grave shafts. In the case of the Charles City site, the stripping revealed no graves in the vicinity of a proposed new driveway. However, the archaeological team discovered several other cultural features that indicated that a house had once existed on the site. While the property owners were not obliged to conduct any archaeological work by local, state, or federal regulations, they allowed DHR and volunteers to conduct a salvage operation to retrieve important information from the site.

The delineated cemetery contains only one formal stone marker and approximately five additional depressions indicating graves in the immediate vicinity. The stone marker identified the grave of Rebecca Marston, a woman who died in 1857. Research shows that Rebecca was born into the Eppes family in 1813 and married Thomas Marston when she was about 20 years old. Records reveal that she had four sons and two daughters when she passed away at 44 years old. Based on historic maps, the cemetery appears to be on the Eppes family’s property. While the maps of the era show several Marston homes nearby, it remains unclear which one of the houses belonged to Thomas and Rebecca.

The cemetery delineation unearthed several backfilled postholes representing at least one post-in-ground structure. Remnants of the posts that decomposed in place—known as post-molds—were found inside the postholes. In distinct contrast to the natural clay found in the area, the postholes show up as a mix of the dug-out soil used to back fill holes. Due to the presence of wood that once made up the post, the post-mold often yields a much darker organic stain than the natural clay. A picture of a post feature is included in this article. The removal of the topsoil also revealed two large dark features, roughly in the shape of squares, that measured about three feet in length and width. Both features were contained within two rows of post-features. Experience led us to believe that these indicated subfloor storage pits, sometimes thought to be root cellars. Since the team did not find artifacts in the topsoil that had been removed, nor did they see any artifacts exposed on the surface of these features, the time period of occupation remained a mystery.

The first task was to hand trowel the entire exposed surface to identify, photograph, and map each of the features present. This is a time-consuming and yet satisfying job. It is the point at which the site will be its cleanest and every feature most visible for documentation. Once that was completed, the team began bisecting the larger cellar features by removing half of the fill soil in each. This is done by establishing a midpoint line and then removing the soil from that half by layer, which leaves intact a center wall that shows the fill episodes that resulted in the backfilled feature. It is likely that these features were backfilled near the end of the life of the structures and after the goods stored in them had been removed.

While the team did not find any artifacts before the excavations at the site, they were surprised by the amount of data they were able to recover from the features. The materials they found were extremely datable and representative of a very tight window in time. The largest category of artifact recovered from the site is known to archaeologists as cheetos, which are highly corroded nails and other metal fragments. The identifiable nails were all hand-wrought—each had been made by a blacksmith. These were the only types of nails available before the 19th century as the use of cut nails did not start until about 1800. This information gave the team their first clue regarding the age of the site.

The second largest category of artifacts recovered was ceramics. The team found multiple fragments of white salt-glazed stoneware, tin-glazed earthenware, two sherds of Staffordshire type ware, small fragments of Westerwald, and two small sherds of early creamware. The team also recovered fragments of at least two colonoware ceramic bowls. Colonoware, a topic long debated among professionals in archaeology circles, ultimately refers to a locally made ceramic-type object that often resembled European-style ceramics in form. Some early types of colonoware dating to the colonial period were made by Native Americans. Some were made by enslaved people of African origins. Created from local clay, colonoware is generally unglazed and its surface is almost always burnished and smooth. Colonoware is mainly associated with the living quarters of enslaved people. One vessel that the team identified is well burnished and made of orange clay. It appears to have been a very simple bowl. The team uncovered multiple fragments from this vessel. The other vessel that the team identified is a thin black-and-gray bowl with a distinct lip on the rim. Several fragments of that bowl were found.

Since colonoware was made throughout the colonial period and well into the 19th century, it is difficult to determine the date of manufacture. Fortunately, the remainder of the ceramics that the team found indicate the site was likely first occupied during the first half of the 18th century. Two sherds of creamware give the team a good terminus post quem (TPQ), a Latin term meaning “date after which.” Based on several characteristics, the team deduced that the creamware was created shortly after its introduction to the market following 1762. This led the team to conclude that the sherds could not have ended up on the site until after that year. All the other wares uncovered from the site consisted of common types that were made from the 17th century well into the 18th century, though most of them were largely out of fashion by the 1770s. It seems likely that the creamware was left here sometime during this general period.

The team also recovered more than 20 fragments of tobacco pipe stems and bowls from the site. Archaeologists determine the origin and the date of a tobacco pipe by its bowl shape and the hole size on its stem. In the 1950s, archaeologist J. C. Harrington used drill bits and studied pipes from sites with known dates to determine that the hole in the pipe stems decreased in size over time in regular 30-year intervals. Thus, a pipe made in 1620 had a hole of about 9/64 of an inch in diameter, while a pipe made in 1740 had a diameter of 5/64 of an inch. The pipes found at the Marston site featured holes ranging somewhere between 5/64 and 4/64 of an inch. This indicates that the pipes were made sometime between circa 1720 to the end of the century. Additionally, several of the pipes are made of locally sourced red clay, unlike the white-clay pipes imported from England.

Finally, the team also recovered personal items from the site, including buttons and buckles. While datable, archaeologists would have to work with a wider range of years to determine the dates of origin for these items. The team found one-half of a pair of sleeve buttons. These buttons were made in linked pairs for the wearer to attach to shirt sleeves, like cuff links. The sleeve button from the site (pictured in this article) features a copper back with a hand-painted ceramic inlay. The team also found two larger pewter buttons: one rather plain in style while the other boasted an engraved decoration on the front. Other personal items recovered include one small clothing buckle and one decorative shoe buckle with remnants of what appears to be silver.

Considering the information derived from the excavation—from the presence of colonoware and a post-in-ground structure, to the overall paucity of artifacts, to the site’s location on a known plantation property—the team concluded that the site had once been the home of enslaved people in the 18th century. It is common to find a variety of handed-down ceramics at historic sites associated with enslaved people. The presence of creamware, usually handed down from the main house of a plantation, indicates the site was occupied at least until the 1760s and maybe a little later. The types of the other wares, which were also likely handed down, had gotten well past the peak of popularity by the time this site was abandoned. The absence of pearlware, a white tableware created starting in the late 1770s that featured a hint of cobalt, indicates that the site was probably abandoned by the 1780s. The combined tobacco pipes range from 1720 at the earliest, to approximately 1800 at the latest, with an average somewhere around mid-century. The few small fragments of bottle glass that the team found were undatable but are representative of typical glass from the 18th century. The existence of a post-in-ground structure, which would have had a 25- to 30-year lifespan, combined with the evidence provided by the ceramics and pipes, suggests that the Marston site was inhabited from about the 1740s to the 1770s.

In the end, there is still little information about the site and its inhabitants. Undoubtedly the site extends much farther than the portion the team was able to excavate. There may even have been small dwellings clustered nearby. Further research into the Eppes and Marston families, such as looking into an early plat or a probate inventory, may reveal more information about the individuals who once lived and worked on the property. What is certain is that an enslaved person, or a family or a group of enslaved people, made their home at this site for at least a quarter of a century. They likely worked in the neighboring fields. They were probably given the old dishes when the plantation owners bought a new set. It can also be deduced that the people who lived at or near the site made their own pottery and tobacco pipes. They may have done that out of necessity or for a supplemental income. Perhaps the most intriguing of the artifacts recovered from the site is the decorative sleeve button. Beyond merely utilitarian, it seemingly represented a personal item, a small piece of beauty in a world filled with endless labor and struggle.