Virginia Landmarks: A Showcase of Successful Historic Preservation Projects

Before and after photos highlighting a few of the Commonwealth's most memorable preservation success stories from years past.

By Lena McDonald

A popular section of DHR’s website is the Virginia Landmarks Register Online, or VLR Online, where all of the properties listed in the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places are featured. Thousands of historic places across Virginia are part of VLR Online. At the time of listing, a property may be in pristine condition, or in need of minor repairs, or appear to be dilapidated. Fortunately, poor physical condition does not prevent listing a place in the historic registers. In fact, listing is often a pathway to bringing a historic property back into use and making it a part of the community again.

The Scrabble School in Rappahannock County had fallen into disuse after it closed as a public school in 1967. Constructed between 1921-1922, the Scrabble School was the first school in Rappahannock County to be built under the auspices of the Rosenwald Fund, a philanthropic effort conceived by Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute, and Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck & Company.

A community group made of school alumni and local residents organized to establish the Scrabble School Preservation Foundation, with the mission of preserving the building and sharing its legacy through educational programs. Community-based efforts such as these are often vital to successful historic preservation projects, especially for places with deep roots and cultural importance.

As is explained in the school’s nomination, the impetus for the school’s preservation began in the early 1990s with a notable alumnus, the late E. Franklin Warner, who envisioned the school as a vibrant community center. In November 2005, the Board of Supervisors for Rappahannock County approved the former school’s reuse as a recreational space for the county’s senior citizens and a heritage center. The Board of Directors of the Foundation then successfully applied for various private grants and received donations from numerous individuals to pay for the building’s rehabilitation. The Foundation also worked closely with the Carter G. Woodson Institute at the University of Virginia in conducting oral histories, thereby assuring that the memory of Scrabble School’s community significance would be preserved as well as the building.

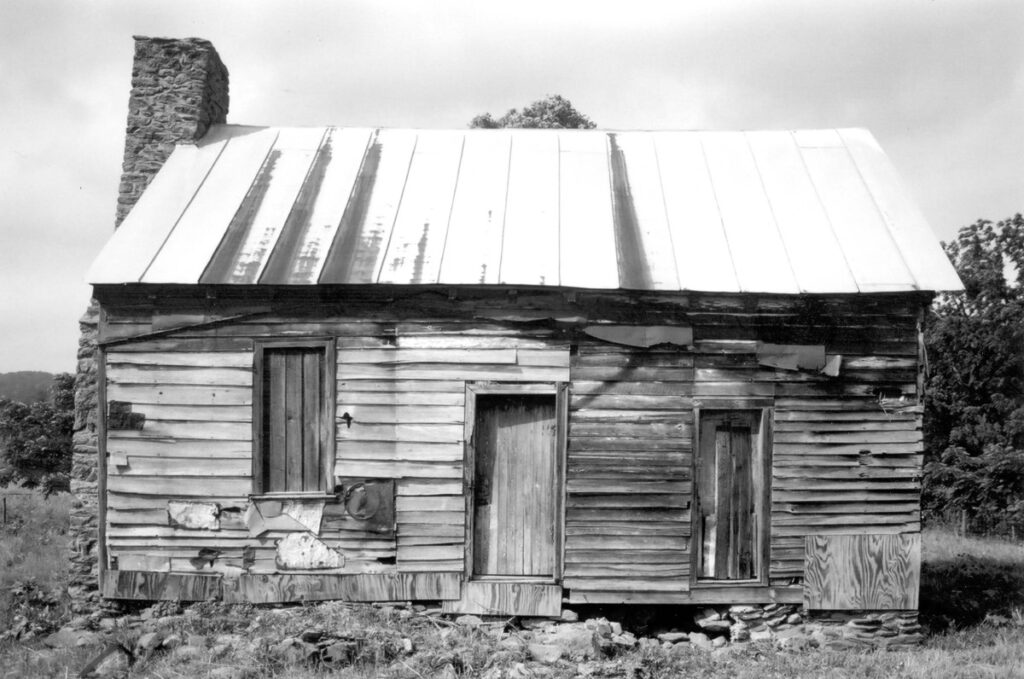

In Fauquier County, another dramatic transformation occurred at The Hollow, once the residence of Thomas Marshall, father of U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. In 1763-1764, Marshall built the dwelling named for the valley that surrounds it, where the future Chief Justice spent part of his boyhood after age nine. Its early date of construction makes The Hollow a rare survivor today, but by the late 20th century, it was not suitable for habitation.

An example of a hall-and-parlor house, one of the most common dwelling types of the 18th century, The Hollow had deteriorated even further by the time of its listing in the historic registers in 2003.

Dr. David C. Collins, CEO of Learning Tree International, purchased The Hollow and sponsored a program of architectural and archaeological investigations to inform restoration of the dwelling to its 18th-century appearance. Friends of the Hollow Inc. was created to manage the preservation of the building. Over the next two decades, a careful restoration project was carried out, bringing the hall-and-parlor house to its current condition.

The Hollow is among the historic properties included in John Marshall’s Leeds Manor Rural Historic District that encompasses more than 23,000 acres in the northwest section of Fauquier County. The district’s name comes from its association with the 18th-century Manor of Leeds, which once was part of Lord Fairfax’s Northern Neck Proprietary, and the Marshall family, who bought the land from Lord Fairfax’s heir in 1781. Chief Justice John Marshall, with his family and associates, farmed much of the land well into the 19th century.

A few more dramatic transformations between Register listing and conditions today are below. Such restoration successes are due to the efforts of countless private individuals whose energy, expertise, financial acumen, and desire to preserve Virginia’s heritage have proven essential to protecting these historic places today and for future generations. DHR staff frequently add new photos to VLR Online; even frequent visitors are likely to find something new to enjoy.

•••

•••

•••

•••

•••