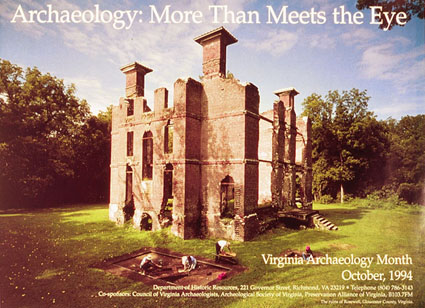

Preservation: Archaeologists are advocates for preservation and the care of historic resources.

Lab work: Archaeology labatory activities include cataloging, conservation, analysis, and research.

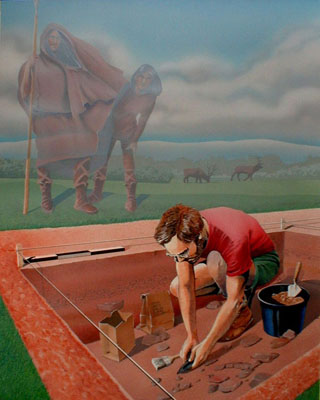

Field work: Archaeology field activities include survey, excavation, and remote sensing.

Resources for Virginia Archaeology

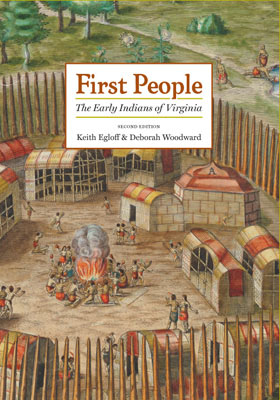

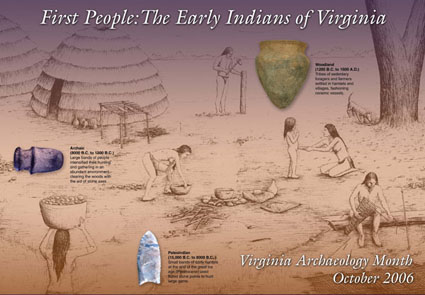

First People: The Early Indians of Virginia by Keith Egloff and Deborah Woodward:

This book incorporates recent events in the Native American community as well as additional information gleaned from publications and public resources. First People (second edition, 2006) brings to the fore a concise and highly readable narrative. Full of stories that represent the full diversity of Virginia’s Indians, past and present, this popular book remains the essential introduction to the history of Virginia Indians from the earlier times to the present day. Purchase through local bookstores, online or through University of Virginia Press.

FAQ

Question: Where can I go to get more information on archaeology?

Answer: One can go to books, organizations, and websites.

Question: What are some good books that I can read?

Answer: There are many books and magazines on Virginia archaeology. Many of these publications are listed on websites.

Three good books to start with are: “First People: The Early Indians of Virginia” by Keith Egloff & Deborah Woodward; “Jamestown, The Buried Truth” by William M. Kelso, both published in 2006 by the University of Virginia Press; and “A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America” by Ivor Noel Hume, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Question: Is there an organization that I can join?

Answer: The Archaeological Society of Virginia (ASV) is composed of a mix of professional archaeologists and other people who are interested in archaeology. Archeological Society of Virginia, 12106 Weyanoke Rd. Charles City, VA 23030. Phone: 804-829-2272. virginiaarcheology.org

Question: Is there a site where I can volunteer?

Answer: Please visit the Archeological Society of Virginia website for a listing of field schools and other field and lab opportunities across Virginia, or contact the ASV for more information.

Preservation

Almost all of what we know about people who lived here previously but did not leave written records has been learned from archaeological sites. It is important to understand the serious and urgent need to preserve these sites. Many are in danger of being destroyed. Each site is unique in the information it contains. It cannot be replaced. When sites are damaged before archaeologists can study them, the information–and our understanding of the past–is lost forever.

Sites are destroyed in two ways: by nature and by man. Natural forces wear down the earth’s surface and gradually remove traces of any markings, postmolds, and material remains. Normally, exposed areas on high or sloping ground are the ones most battered by wind, rain, and water. Rivers and the Atlantic Ocean also slowly erode land and can damage sites.

Man can unwittingly destroy sites in the normal course of constructing houses, roads, lakes, and factories. Even the very important work of cultivating fields to raise food may harm sites through soil erosion. A survey of an area before any building or farming begins can reveal the hidden assets beneath the ground. In some cases, developers have included newly discovered sites in their project plans. Some sites have become the focal point of a residential neighborhood or district, adding richly to a community’s sense of the past.

Unfortunately, man also destroys sites through acts of collecting. Artifact collectors often dig for treasure, hoping to discover something of great value. They sell the objects to make money or keep them to build a collection. Collectors place no cultural value on the site from which they are taking the artifacts. While they dig for treasure, they destroy the real find–hamlets, villages, and tribal centers that hold clues to our shared past. In just a few generations, the archaeological remains of 17,000 years of human activity could be nearly destroyed by progress and collecting.

Several laws help to protect archaeological sites in Virginia. The federal Archaeological Resource Protection Act (1979) and the Virginia Antiquities Act (1977) prohibit removing, without a permit, all cultural resources on government property. The Virginia Cave Act (1979) bars excavation without a permit within all caves and rockshelters. State burial laws prohibit removing, without a permit or court order, all human burials, regardless of age or cultural affiliation.

The National Historic Preservation Act (1966) requires review by archaeologists on federally funded, assisted, or permitted projects to consider their impact on important archaeological sites. Often this review results in the excavation of a site before construction, or altering the project plans to avoid the site. However, the fate of most archaeological sites is determined by private development, to which few if any guidelines apply.

Including archaeological sites on the Virginia Landmarks Register and on the National Register of Historic Places can also encourage their protection. These two registers do not regulate property owners, but they do encourage preservation of sites by calling attention to their special significance. Property owners wishing to provide for the permanent protection of significant sites can do so by granting a protective easement to the state or to some other appropriate organization.

Organize a Virginia Archaeology Month event in your community. Find a local museum, library, school, historical society, or other organization to sponsor an exhibit, lecture, or other event. The Department of Historic Resources or the Archeological Society of Virginia can help you develop ideas and find speakers. They can also send posters and other information to use at the event.

Read. The more you know about what can be learned through careful archaeological study and analysis, the better you can explain to others the importance of protecting archaeological sites. Both the Department of Historic Resources and the Archeological Society of Virginia publish books and reports about Virginia archaeology. Public and college libraries are good sources for both books and magazines about archaeology. You can also find Archaeology magazine in many bookstores.

Join the Archeological Society of Virginia. This statewide organization is made up of people like you who want to learn about Virginia’s history and prehistory by studying and protecting archaeological sites. The society publishes a newsletter and the Quarterly Bulletin with reports on archaeological sites and issues, and it sponsors many events each year. There may be a local chapter in your area with even more things to do. For more information visit: virginiaarcheology.org

Don’t dig. Each site is a unique page in the story of Virginia’s past. Whether it is for curiosity or greed, digging for any reason destroys the context of a site. If the site is skillfully excavated under the eye of an archaeologist, that unique page can be read, recorded, and retold. If that careful reading does not happen during excavation, then the site and its story are both gone forever; the recovered artifacts may look interesting, but their true meaning will remain obscure.

Participate in decisions that affect archaeological sites. Local governments and state and federal agencies that own property or that make decisions about zoning, permits, construction, highways, and similar activities that may damage archaeological sites usually have a way in which citizens can participate in those decisions. If you contact your local government or the individual agency to learn about these procedures, you can let the decision makers know that you think archaeological sites are important. This would also be a good project for a history or civics class as a way to learn how local governments make decisions.

Learn how to identify and report sites. We can’t preserve or study sites unless we know where they are. The Department of Historic Resources (DHR) maintains a list of sites all over Virginia. These lists can be used by researchers and by people making decisions about building roads and other large developments. Both the DHR and the Archeological Society of Virginia can help you report sites. For more information visit: virginiaarcheology.org

Join the Archaeological Conservancy. Consider joining the Archaeological Conservancy. The Conservancy actively seeks sites in Virginia to protect until they can be properly and conservatively researched. Membership in the Conservancy includes a subscription to American Archaeology magazine. For more information visit: http://www.americanarchaeology.com/

Volunteer to work on a site or in a lab. Many ongoing archaeological projects welcome volunteer assistance, especially to help process artifacts in the laboratory. Since digging–even by archaeologists–destroys the site being studied, make sure that the project you choose is one that is conducted to meet state and federal standards. The Department of Historic Resources maintains information on some of the projects that welcome volunteers. Contact the individual project sponsor for information on volunteer programs and schedules.

FAQ

Question: If I find an artifact, should I dig?

Answer: No. Each site is a unique page in the history of Virginia. Please contact a professional archaeologist to record the site.

Question: If I find an archaeological site, who should I tell?

Answer: Please contact a professional archaeologist at the Department of Historic Resources or refer to the Council of Virginia Archaeologists (COVA) website (http://cova-inc.org/) for a listing of professional archaeologists.

Question: If I want to preserve an archaeological site on my property, who should I contact?

Answer: Contact either the Department of Historic Resources or the Archaeology Conservancy.

Archaeological Conservancy, Eastern Regional Office, Director Andy Stout, 8 East 2nd Street, Suite 200, Frederick, MD 21701, 301.682.6359

Lab work

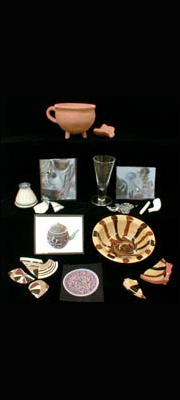

Lab work encompasses all the inside work that archaeologists do, once the artifacts have been excavated. This starts with washing, cataloging, mending, and conservation; goes to collection care of the artifacts and records; and finally leads to analysis, research, exhibit, and education.

Dig Deeper

FAQ

Question: What is an artifact?

Answer: An artifact is a general term for tools, weapons, utensils, and other items used by humans.

Question: How do you know the age of an artifact?

Answer: For sites that contain layers of soil, the artifact in the lowest layer is oldest.

Radiocarbon dating, developed in the 1940s, is an absolute dating technique commonly applied in archaeology on prehistoric sites. Anything that was once alive can be radiocarbon dated. Thus any artifacts found in association with material that has been radiocarbon dated are dated by association.

On historic sites, the age of artifacts can often be determined by researching early documents.

Question: How do you catalog an artifact?

Answer: A catalog is the description and count of artifacts. Different tables with multiple attributes are used to catalog artifacts. The artifact catalog is entered into a database so that archaeologists can search on artifact type or any combination of attributes.

Question: How do you conserve a rusty iron artifact?

Answer: Conserving any artifact, depending on the type of material, is a specialized science that only professionally trained people can do well. A conservator will proceed through steps that clean, stabilize, desalinate, and seal the artifact from further corrosion.

Field work

Field work encompasses all the outside work that archaeologists do. In general, this includes looking for sites — surveying; evaluating their research potential — testing; and recovering information from the site — excavation. Archaeologists normally use shovels and trowels to excavate; various-size screens to recover a wide range of artifacts; paper, pencil, and transit to map and keep records; and cameras to document what was uncovered.

Screening soil with water through fine mesh screens, rather than by hand through large mesh screens, can recover items as small as 1/16 inch. Items like small glass beads, fish bones, and charred nut and seed fragments may be recovered.

Flotation is different from water screening. For flotation a soil sample is placed in water, agitated, and filtered through an extremely fine screen, leaving behind both a light fraction (items that float to the top, such as bits of charcoal or charred seeds) and a heavy fraction (items that do not float). The charcoal and charred nuts and seed fragments are then identified to help document the environment and what people gardened and gathered for their diet.

Soil samples may be sent to a specialized laboratory to identify the pH readings and chemicals, such as phosphates and calcium in the soil. Soil chemical analysis is an important way to understand past activities that occurred in different locations within a site.

Plants produce pollens and phytoliths that can be preserved in the ground for thousands of years and can provide detailed evidence of past environments. Pollen grains allow archaeologists to understand the trees, bushes, and plants from past environments and how people may have used them.

Images of grid excavations

FAQ

Question: What is archaeology?

Answer: Archaeology is a subfield of anthropology, which is the study of people. Archaeology is the scientific study of past cultures through the systematic recovery and interpretation of their material remains (artifacts).

Question: How do you know where to dig?

Answer: Archaeologists look for artifacts on the surface of the ground in places that are environmentally desirable to live, such as well-drained land near streams.

Question: How deep do you dig?

Answer: Since the surface of Virginia is eroding down, most archaeological evidence is contained in the top three feet of soil. Deeper sites are typically found in flood plains or as cellars or wells on historic sites.

Question: How do you understand what is in the soil?

Answer: The soil is carefully excavated and troweled to bring out the color and texture. An archaeologist reads the soil to identify different layers and features that can be seen in the soil with a trained eye. Recognizing and maintaining the context of the artifacts in the layers and features is most important.

Question: What is the most valuable artifact that you have found?

Answer: The site is the most valuable artifact to an archaeologist. Without the context that a well-preserved site provides, the other artifacts provide very little information about the people who lived there and their culture.