—New listings cover sites in the counties of Amherst, Carroll, Fairfax, King and Queen, Loudoun, and Wise, and a Boundary Increase for the Norfolk Auto Row Historic District—

—VLR listings will be forwarded for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places—

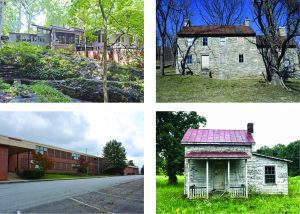

A plantation once owned by George Washington, a town in Southwest Virginia’s Wise County that boomed during the era of King Coal, and a public school in Carroll County that established the state’s first agricultural curriculum in 1917 are among the six historic places added to the Virginia Landmarks Register by the Department of Historic Resources on September 20 during the quarterly meeting of DHR's two boards. In Fairfax County, the Woodlawn Cultural Landscape Historic District began as a 2,000-acre plantation owned by George Washington that he gave to his ward, Eleanor Parke Custis, and her husband. The acreage later diminished in size—partly absorbed by the Army’s expansion of Fort Belvoir during the 20th century—but grew in stature as a landscape defined by events, buildings, structures, and sites important to the history of Fairfax County, the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the United States. The district’s multi-thread story is evidenced in four properties previously placed individually on the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places: Woodlawn Plantation, listed in 1970 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1998; George Washington’s Grist Mill (listed, 2003); Woodlawn Quaker Meeting House and Burial Ground (2011); and the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed Pope-Leighey House (1970). The Woodlawn district is also significant for its African American heritage as a former plantation and, beginning in the 1850s, the site of an integrated community of free blacks and whites. That community arose after northern abolitionist Quakers purchased the Woodlawn Plantation around 1845 with the primary aim of establishing small farms, between 50 and 200 acres, to be owned by whites and free blacks. The implementation of that social experiment at Woodlawn gave rise to a productive farming community that highlighted its “free” labor in a slaveholding state. During the late 19th and 20th century, the original Woodlawn Mansion drew a succession of preservation-minded property owners who enhanced and restored the house. In 1948 the mansion passed out of private ownership after the Woodlawn Public Foundation enlisted the support of the first nationwide private preservation organization, the National Council of Historic Sites and Buildings, to “Save Woodlawn for the Nation.” That campaign, which led to the Woodlawn foundation taking possession of the house in 1949, inspired the founding of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Other notable sites within the Woodlawn Cultural Landscape Historic District include the Woodlawn Baptist Church and Cemetery, constructed in 1872 the original sanctuary was replaced by a new one in 1997; Grand View, a two-story vernacular residence with Greek Revival touches, constructed in 1869; the Otis Tufton Mason House, dating to 1854 with subsequent additions around 1873 and 1880; and a small portion of the original Alexandria, Mt. Vernon, and Accotink Turnpike, largely superseded by today’s US 1. Wise County’s Big Stone Gap Downtown Historic District is nestled in the Alleghany Mountains of western Virginia. The “Big Stone Gap” refers to the broadening of the Powell River Valley between Stone Mountain, Little Stone Mountain, and Wallens Ridge. The district comprises the historic business core of Big Stone Gap, a boomtown that flourished from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century as the hub for emerging coal and iron-ore industries in Wise County. Unlike many towns in the region that arose unplanned, the Big Stone Gap Improvement Company laid out the town on a grid plan in the 1880s. The Stonega Coke and Coal Company, a pioneer in coal production in Southwest Virginia and the largest producer in its territory, built its headquarters in Big Stone Gap in 1908, further elevating the town’s importance. Coal extraction continued as the major local industry throughout the mid-20th century, stimulating the town’s commercial development in support of the growing industry and its employees. The Big Stone Gap’s historic district includes architecturally significant individual buildings, such as the 1912 Renaissance Revival-style Slemp Federal Building and the 1940 Moderne-style Tri-State Coach Bus Terminal, and vernacular commercial buildings constructed from 1900 to the mid-20th century, clustered mostly within a four-block area. Because a 1908 fire destroyed many buildings associated with the town’s boom period in the late 1800s, the ten-acre district’s oldest building dates to around 1900. Carroll County’s Woodlawn School, one of its largest and longest-operating educational institutions, served all grades for most of its history, shaping generations of county youth. The 21-acre campus saw construction of the county’s first public high school completed in 1908 and subsequently incorporated into later additions. The school added a home economics cottage for classes beginning in 1916 and an agricultural building behind the school for the state’s first vocational agriculture courses in 1917, part of a federal agricultural education program. Over time its agriculture department offered instruction in farm administration, crop cultivation, fertilization, erosion control, livestock care, and building maintenance and construction, topics all critically important in a rural county with a farming economy. The school’s agricultural curriculum resulted in higher farm yields in Carroll County, as well as crop diversification, and substantial investment in dairy and beef production. The availability of a wide range of academic and vocational courses at Woodlawn School boosted enrollment and graduation rates as the 20th-century progressed and led to additions to the original 1908 two-story, classically-inspired brick school in 1937, 1953, 1962, and 1974 to accommodate changing curricula and student population growth. Woodlawn School operated as the largest of Carroll County’s four intermediate campuses until 2013, when the school closed. Elsewhere in Virginia, three other listings were added to the Virginia Landmarks Register by DHR’s Virginia Board of Historic Resources during its September quarterly meeting.Programs

DHR has secured permanent legal protection for over 700 historic places - including 15,000 acres of battlefield lands

DHR has erected 2,532 highway markers in every county and city across Virginia

DHR has registered more than 3,317 individual resources and 613 historic districts

DHR has engaged over 450 students in 3 highway marker contests

DHR has stimulated more than $4.2 billion dollars in private investments related to historic tax credit incentives, revitalizing communities of all sizes throughout Virginia