Cornerstone Contributions: Annual Reunion Pegram Battalion Association

The author examines the growth of Confederate veterans' organizations in the late 19th century, with a focus on the association of those who had fought under the command of Col. William Pegram in the 3rd Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia.

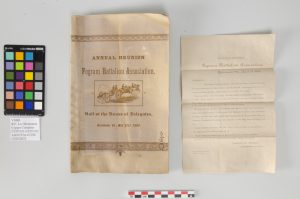

The veterans of Pegram’s Battalion marched into the House of Delegates chamber of the Virginia State Capitol and sat to witness what was to them a sacred ceremony. It was 1886, twenty-one years after the battlefield death of their namesake commander—Colonel William R.J. Pegram—in the last week of the war. After a prayer, W. Gordon McCabe, the Battalion’s wartime executive officer, arose and—on behalf of Pegram’s mother—presented the Battalion’s battleflag to the Pegram’s Battalion Association for safe keeping. McCabe recounted the Battalion’s history and entered into a long oratory about Pegram. Almost as an afterthought, the Association also took possession of Pegram’s sabre. The ceremony closed with a benediction, and the attendees crossed Broad Street and settled into dinner, drinks, and ceremonial toasts at Saegner Hall.

The 1880s and 1890s had seen the flourishing of veterans' organizations and activities in Richmond. Groups like Pegram’s Battalion Association, The Richmond Howitzers, the Association of the Army of Northern Virginia, and the Veteran Cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia were social and cultural gathering spaces for veterans at the peak of their economic and political power. These groups met in annual meetings to reminisce with comrades and remember the old days. Every gathering from an association picnic to the funeral of prominent members earned a notice in Richmond’s White newspapers.

Their meetings were more than just nostalgia. These associations worked hard to fundraise and lobby for the erection of monuments to their men and their commanders. After the 1886 meeting, Pegram’s Battalion Association took a leading role in the creation of the A.P. Hill monument presently at the intersection of Laburnum and Hermitage in Richmond. They also entered into fundraising for the care of elderly and infirm veterans at the R.E. Lee Camp No. 1’s Soldier’s Home. As part of the effort, they installed a memorial window to the Battalion in the Soldier’s Home chapel.

Interestingly, Richmond’s web of Confederate veteran associations worked hand-in-hand with United States veterans in the Soldier’s Home project. The Grand Army of the Republic, spearheaded by Richmond’s Phil Kearney Post, No. 10, donated a great deal of money to the Confederate veteran home. This cooperation made sense to the men involved. After all, four years of killing one another had given way to an uneasy peace and ongoing tension as former Confederates resisted efforts to enforce racial equality during Reconstruction.[1] Symbols of sectional comity were not ubiquitous in the 1880s, so the veterans sought any opportunity to share fraternal moments that promised peace and satisfied the emotional and political needs of both sides.

The Pegram’s Battalion veterans in 1886 did not emphasize those specific needs in the speeches contained in this pamphlet, but they are still apparent.

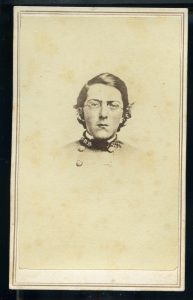

The pamphlet began with McCabe’s tribute to Pegram, noting that “he needs no panegyric in the presence of the men who knew him” and then proceeded to deliver such a public speech to the men who had known him. He traced Pegram’s military career. The twenty-year-old Richmond native left his studies at the University of Virginia to join the Confederate army and quickly rose through the ranks to command, first, the Purcell Artillery battery and then the Battalion of cannoneers attached to General A.P. Hill’s infantry division. McCabe described an unassuming and near-sighted youth with tightly pursed lips who enforced strict discipline and became a battle captain seeking the most desperate assignments and delivering damage to the enemy. Pegram’s adherence to discipline and his love of combat made him a magnetic commander whose men revered him.

McCabe’s adjectives made his points. Resolute, youthful, generous, brilliant, Christian, exact, cheerful, boyish, and noble: they sustained a character study of Pegram and of the Confederate soldier in general as almost perfect and forever pure. Pegram’s former comrades, no doubt, regarded him in such lofty estimation, but it was also an abstraction applied to any Confederate veteran about which veterans themselves talked. It was the same point that Carlton McCarthy had made in his book (https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/news/cornerstone-contributions-carlton-mccarthys-detailed-minutiae-of-soldier-life-in-the-army-of-northern-virginia/). These veterans regarded themselves and their lost comrades as having survived the most grueling test because of their character, courage, and virtue. They insisted so strenuously that it defies credulity. Confederate veterans were “the embodiment of what is noblest in human nature,” one 1886 Association speaker claimed, “and the incarnation of all that is God-like in man!”

They demanded that this incarnation made them able to govern in the present, receive adulation of future generations, and be regarded as the best Americans in the re-United States.

More American than actual United States soldiers who had preserved the Union? One Pegram’s Battalion speaker had an answer for that:

The Confederate infantry was distinctively an American infantry and its victories distinctively the triumph of Americans over armies composed, perhaps in greater part, of recruits drawn from the half civilized nations of the world.

It was this same assumption—their own native ethnic and racial superiority—that drove their cultural politics in their present. If their former foes and their former slaves would just accept the fact of their wartime courage and of their superiority in the present, they reasoned, then they would be happy to “rejoice…in the integrity of the Union” and even to be “glad that the slaves had been set free.” Reunion was a fact settled by Appomattox, but reconciliation would only happen on their terms.[2] It became a trope of the Lost Cause and of 20th century Civil War memory that Confederates represented something wholesome while the U.S. Army had been composed of the flotsam of the modern world with the exception of some courageous native-born Americans.

The Association found these sentiments so compelling that they had the speeches printed and distributed widely. It survived not only in the cornerstone box but also in numerous libraries and archives today, a testament to the veteran’s regard for their fallen comrade and to what they wanted from the present and the future.

—Christopher A. Graham

Curator, American Civil War Museum

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR's archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

References:

[1] Elizabeth L. O’Leary, Across Time: The History of the Grounds of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2019)

[2] M. Keith Harris, Across the Bloody Chasm: The Culture of Commemoration Among Civil War Veterans (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014)