Spotlight on DHR Collections: "Betsy" Dining Utensils

What do dining utensils tell us about life aboard Betsy, a 1772 British supply vessel for General Charles Cornwallis’s fleet?

Betsy was one of several ships strategically scuttled during the Battle of Yorktown in 1781. During underwater excavations in the 1980s, under the direction of Dr. John Broadwater, archaeologists recovered a number of utensils from Betsy including forks, knives, and spoons, all made from a variety of materials and in an assortment of styles. Fortunately, the underwater environment preserved the wooden and bone artifacts, allowing conservators to clean and treat them for study and exhibition.

(Photo shows an archaeologist recovering artifacts from Betsy during excavations in the late 1980s.)

From these discoveries, it is evident that flatware reflected fashion, cuisine, and dining practices aboard Betsy. A variety of styles, all dating from the last quarter of the 1700s, demonstrates that the sailors aboard Betsy provided their own utensils. Had the British Navy issued flatware to the seamen aboard Betsy, similar uniform styles would be evident in the assemblage. Archaeology demonstrates that this was not the case.

Furthermore, the flatware found was economically priced: made from a combination of steel utensils enhanced with handles embellished with cheap, bone slats that scholars refer to as “scales.” The bone scale handles of this economical flatware mimicked more expensive cutlery that was produced using an entire bone or antler.

Archaeologists recovered spoons made from pewter and wood as well. Pewter is a soft metal and one recovered pewter spoon handle illustrates how one clever sailor modified his spoon to repurpose as an awl, used for puncturing materials. One can only speculate on the nature of the activities to which this spoon awl was applied.

Wooden spoons were the cheapest available. The short handle on the specimen shown below likely made it easy to carry in a pocket, an advantage aboard a ship where space was limited and keeping track of personal belongings could be challenging.

The bulbous end on the utensil handle pictured above categorizes it as a ‘pistol’ grip, a style developed in the late 1600s. The two yellow arrows indicate the apertures where metal pins attached the handle to the metal flatware, a fork or knife.

In the photograph above, both halves of this complete, bone utensil handle are present. The slightly widening end is reminiscent of the popular pistol grip, which suggests that it was produced near the later years of the popular ‘pistol grip’ form.

Starting in the 1750s, straight edges in all kinds of materials—buckles, furniture, and other decorative arts—became fashionable. The bone utensil handle in the photo above exhibits straight edges, popular by 1760, reflecting the latest fashion at the time the British scuttled Betsy.

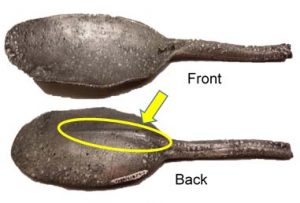

The image above shows a pewter dining spoon with a ‘rat tail’ (yellow circle and arrow) on its back. The rat tail was a stylistic spine that ran down the reverse side of the spoon. Rat tails were popular throughout much of the 1700s.

Wooden spoons were widely used, and the specimen above boasts an evident rat tail on the reverse side of its deep bowl, revealing that the common stylistic feature was not limited to metal spoons of the 1700s.

Repurposing of items on a ship of the era was common practice. For example, someone re-used this pewter spoon handle by modifying it to produce a sharp point (see arrow). The refashioned implement was used to puncture some kind of thick material—perhaps leather or canvas—in the manner that awls are used. Such use bent the tip from the pressure exerted on it.

Although fragmented, the bowl (above) of a wooden spoon is clear to see. The bowl is well formed, and deep, suggesting its use by an individual whose meals consisted of food that contained larger pieces of vegetables, fish, and meat—as opposed to the pureed soups popular among the French cuisine at this time.

—Laura J. Galke

Chief Curator, DHR